(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1837

Died: 1926

Summary of Thomas Moran

As a nineteenth-century American painter, Thomas Moran was one of the most influential. Thomas Cole’s signature style of spiritually-infused naturalism was adopted by the second generation of great American landscape painters, who adapted it to new landscapes. However, unlike Cole’s admirers, such as Frederic Edwin Church, who focused on the Andes in South America, Moran was more interested in the vastness of the Rocky Mountains and Yellowstone National Park in the western United States. To the imagination of the North American settler community, he opened up a whole new part of the North American landscape with paintings that were arguably superior to Cole and Church in terms of divine yet naturalistic grandeur; his seas and skies recall J.M.W. Turner’s sublime quality.

The Rocky Mountain School is often referred to as including Thomas Moran. One of several artists (including Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill and William Keith) who contributed to the Hudson River School of painting by depicting the more rugged and expansive landscapes of the American West, though he was not a’school’ in the conventional sense. As Cole et al. adapted the European-Romantic aesthetic in their work, a direct line can be traced back. It is possible that their combined European and American identities enhanced the Northern European Romantic aesthetic in their work, such as in Bierstadt, Keith, and the English-born Moran.

Many of Moran’s contemporaries were inspired by J.M.W. Turner’s work. Moran, on the other hand, may have been the only nineteenth-century landscape painter in the United States to inherit Turner’s rugged magnificence. More so than any of his contemporaries, Moran’s best canvases share with Turner the qualities of sublime beauty with a deep sense of human emotion, making them less glossy and overdone than their peers.

Sublime art, as demonstrated by Moran’s work, is characterised by a sense of terror and awe in the viewer when confronted with large natural or man-made spectacles. They appear so vast and alien in his work that they seem somehow impervious to the scales of human experience and emotionality. American landscape painters like Moran and Caspar David Friedrich borrowed this quality directly from European predecessors of the eighteenth century.

American popular culture is shaped by Moran’s depictions of the American West. Despite the fact that he opened up these landscapes to the tourist industry, his work has been critical to the preservation of these places. He was instrumental in the creation of Yellowstone National Park, for example, thanks to his paintings of the area. Even today, many Americans are inspired by his paintings, which depict a landscape that is becoming more and more ravaged by human activity.

Childhood

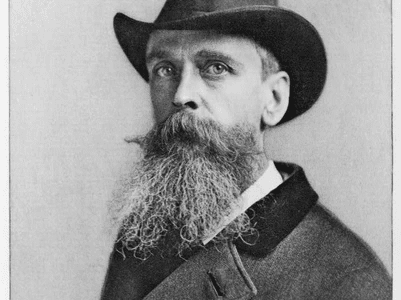

He was born in Bolton, Lancashire on February 12th, 1837 in the English industrial heartland, which was also Thomas Cole’s childhood home. One of seven children, Moran was the son of Mary (née Higson) and Thomas Moran Sr., who were married for 63 years. With the invention of the power loom, the skills of his family’s handloom weavers were rendered obsolete.

There were financial hardships for Moran’s family during his early years. It is said that Moran’s father wanted his children to be free of the British class distinction and starvation of being a handloom weaver, according to Thurman Wilkins, his biographer. In 1844, he brought his family to the United States, drawn by the promise and economic potential of the new world. For seven-year-old Moran, the crossing was a life-changing experience. Inspired by the waves, he created sketches and paintings of the ocean.

Immigrant textile workers from around the world congregated around the family as they relocated from Baltimore to Kensington, Philadelphia. While growing up, Moran was fascinated by art, and he regularly went to art shows as a child to learn about different styles of painting.

Early Life

He had grown into a “prepossessing youth with gray-blue eyes, high forehead and light brown hair” by the time he was sixteen, according to his biographer. He began his professional career as an engraver at Scattergood and Telfer in Philadelphia, joining a group of American landscape painters, including Asher B. Durand, John F. Kensett, John William Casilear, and George Inness, who all began their careers as engravers.

It’s claimed by Wilkins “Afternoons were reserved for black-and-white drawing by gaslight because working in colour was more difficult in the daytime. He began to arrive at the shop later in the mornings and leave earlier in the afternoons as he became accustomed to the new routine.” Even though Moran had no formal education when he began his career, this early informal training proved invaluable to him.

He quit his apprenticeship at Scattergood and Telfer after three years. For him, the studio of his brother Edward, a successful marine painter, was a place where he felt at home. Moran was introduced to Philadelphia painter James Hamilton, dubbed the “American Turner” who would go on to serve as his mentor and guide throughout the rest of his career.

Wilkins claims that “Moran was never avant-garde in any way. At a time when American art was still heavily influenced by British tradition, he trained and immersed himself in it.” J.M.W. Turner piqued Moran’s interest, and he devoted years of study to his work. His brother accompanied him to London in 1861, where they spent months at the National Gallery studying and copying Turner’s works.

Moran was fortunate in that he was born at a time when romantic landscape painting was becoming a lucrative business. In addition to his good looks, he was a hard worker. To keep up with the pace of his life, he would spend 13 hours a day working in his studio. By rejecting most of the contemporary developments in European Modernism, Moran was influenced by English Romanticism and chose to ignore the 1860 birth of Impressionism. However, the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a distant relative of the European Symbolist movement, inspired him. He was also influenced by the Victorian art critic John Ruskin, particularly by his concept of “truth to nature” which proposed that the artist has a fundamental role in connecting nature and society.

Mary Nimmo became Moran’s wife in 1857, when he first met her. When Nimmo married her husband, the Scottish-born artist began to learn the art herself, becoming a talented artist in her own right. Mary and Ruth were born in 1865, followed by their son Paul in 1864. They were a happy and well-matched couple according to their daughter Ruth: “Music and laughter filled their house on a regular basis. They worked through the night and most of the day, but they still had time to spend with their loved ones.” Despite France’s rich artistic heritage and several visits by the family, Moran was unimpressed by the landscape paintings he saw. Eventually, he would say, “French art, in my opinion, scarcely rises to the dignity of the landscape.” They also visited Italy and Switzerland before returning to the United States and settling in New Jersey.

Mid Life

As a landscape painter, Moran was part of the Hudson River School, which included several generations of American painters from 1825 to about 1870. There is no evidence to support the claim that this group is confined to a specific geographic location, and the name was applied retroactively. Thomas Cole and Thomas Doughty were the school’s most famous early leaders, but they were also well-known for their depictions of the Hudson River Valley in upstate New York. Europe’s Romantic movement was a major influence on the school’s development, but it also had a strong nationalistic bent, emphasising America’s breathtaking wilderness. Moran was also a well-known painter and illustrator in the “second generation” of the School of Paris. More than a thousand commercial images and engravings are attributed to him between 1870 and 1885, mainly to support his frequent trips into the wilderness.

For this reason, Moran is also known as a member of the Rocky Mountain School, alongside Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill and William Keith, for his inquisitive and adventurous nature, which led him westwards away from the Hudson River School’s spiritual home. American West landscapes were transformed into works of art by Hudson River School-influenced artists of this school.

To some extent, his rise to prominence in this school was a fluke. Moran was asked by Scribner’s Magazine in 1870, when he was still in his early thirties, to rework sketches of Yellowstone National Park made by an expedition member. With such an exciting opportunity, Moran took out a loan to pay for his own airfare. As part of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories’s Ferdinand Hayden survey, he spent 40 days in Yellowstone in 1873 riding horses and sleeping in a tent. To protect his bony buttocks from the rough terrain while on the road, he had to ride on the saddle with a cushion.

In his journal, he expresses a sense of exhilaration and freedom even though the writing isn’t creatively inspired “A few of my companions fished for trout after descending to the lake’s edge, and they brought back some of the best specimens I’ve seen so far.

After a long day of riding, we built a large fire and cooked our dinner of black tailed deer meat, which I thoroughly enjoyed. For the first time ever, I spent the night sleeping outside under the stars. A light rain fell, but not enough to dampen our spirits.” The trip to Yellowstone was a watershed moment in Moran’s professional life. Trips across the American continent on foot would influence the rest of his professional career. Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran became so enamoured with the West that he was referred to as such.

John Wesley Powell’s government survey took Moran to the Grand Canyon two years later, where he made his first visit to the canyon. During the following year, he went to Mount Holy Cross, a prominent peak in the northern Sawatch Range of the Rocky Mountains that had only been “discovered” the year before. The snow patch on the rocky face of the mountain gave the mountain its name because of its cruciform shape. When he got to his studio, he’d use the sketches and watercolours he’d made while on the road. American landscape painting has come to be defined by the oil paintings created during these trips.

After achieving a certain level of affluence, Moran was able to take his work to the influential English critic John Ruskin. According to a 1913 profile of the artist in The American Magazine, “A sketch of Utah’s “Bad Lands” was presented to John Ruskin by Thomas Moran, and Ruskin exclaimed, “What a horrible place to live in! The answer was a wry ‘Oh’ from Moran, who added, ‘we don’t live there. The vastness of our country necessitates that we only visit these locations for their beauty.” When Moran presented him with an illustration of the Grand Canyon, the critic had to be convinced it wasn’t Turner’s work.

In 1882, without the assistance of an architect, Moran designed and built his family’s Hamptons estate. The couple decorated the walls of their home with artwork and trinkets they’d picked up on their travels. As a tribute to the work of the couple, the house has been preserved and stands today. After Hurricane Sandy nearly levelled the building on East Hampton’s Main Street in 2012, it has since been repaired and restored.

According to art historian Joni Kinsey: “A century after his death, his paintings of the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone National Park were widely regarded as the definitive depictions of these two natural wonders. As in the past, his work was hailed for its ability to accurately depict a location while also being poetic and eloquent “, it’s a. For most of his life, Moran’s work made him wealthy, and he was able to travel widely throughout the landscape that had captured his imagination.

Late Life

Late in Moran’s career, he followed in the footsteps of his hero, Turner, as he pursued a career in the arts. He travelled to Mexico in 1883 and visited the Grand Canyon and New Mexico during that time. Mary Moran, Moran’s beloved wife, died at the age of 47 in 1899. After caring for her daughter, Ruth, who had typhoid fever, she developed the illness herself. For the next 17 years, he lived an on-the-go lifestyle away from the comforts of his parents’ house. He and Ruth moved to Santa Barbara in the early 1920s and stayed there for the rest of his life. At the age of 87, he made his final trip to Yellowstone.

Moran produced more than 1500 oil paintings and 800 watercolours over the course of his career, which spanned his entire life. “The last of America’s romantic painters” and “the “Dean of American Landscape Painters” were some of the tributes he received after his death in Santa Barbara, California, in 1926. The man he was described by his daughter, Ruth, as “in a time when romance was less prevalent, a romantic figure He had a quick wit, a good sense of humour, and a generous heart, but he also had a quick temper and was willing to fight for whatever cause he believed in.” The Thomas and Mary Nimmo Moran Studio in East Hampton, New York, and Mount Moran in the Grand Teton National Park were both named after the artist.

He followed in the footsteps of his predecessors Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, but Moran also believed that American art needed to find its own, indigenous subject matter. As an artist, he felt that he had a duty to preserve the beauty of the American wilderness for future generations. Yellowstone National Park, for example, was made a National Park thanks to his paintings of the area.

Because of his work’s ability to stand the test of time, Moran is regarded as an important figure in contemporary art. Moran was once described by the artist Arthur Millier as a savage “an “old master” on par with Turner and Claude Lorrain, whose work “did not ‘date’ as much as, say, Albert Bierstadt. He was able to transcend a style of painting that had been outmoded by the Barbizon, Impressionist, and finally the hydra-headed Post-Impressionist importations because of an imaginative element in his work.”

Group f/64 members, including Ansel Adams, were among those who were influenced by Moran’s work. Adams, like Moran, was a nature lover, and his work has played an important role in efforts to preserve the American landscape.

As a result of this, perhaps Moran’s greatest significance lies in his ability to influence the public’s perception of themselves and the American nation. According to Joni Kinsey, “He influenced an entire generation of Americans by making remote and mysterious regions accessible to them through paintings, drawings, and illustrations. Thomas Moran’s paintings contributed to making the West a permanent part of the American psyche by giving viewers a visual sense of place.” Robert Allerton Parker was a fan of Moran’s work “expression has become an integral part of our everyday lives. Moran, perhaps more than any other nineteenth century American artist, compelled the American people to see their continent in a new light.”

Famous Art by Thomas Moran

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

1872

As a colorist, Moran’s ability to combine myth and geography is on display in this enormous canvas. The Yellowstone River cuts through the rocky landscape, evoking a strong sense of the primordial in the composition. It stands out against the earthy greens, browns, and ochres of the surrounding landscape in a vivid blue.. In spite of being dwarfed by the surrounding landscape, the river asserts its own authority by dictating the composition’s very shape. The gulf’s rock strata and characteristics are highlighted by swaths of light that descend from opposite sides. This desolate scene is framed by a group of Native Americans, who serve as the only witnesses to the scene’s awe-inspiring grandeur.

The Chasm of the Colorado

1873-1874

Both the solidity of American landscape and the void that surrounds it are emphasised in this piece. At its core, the work depicts an enormous gaping chasm that engulfs everything in its path: light, life, and water. Chasm of the Colorado is a powerful symbol that asks important questions about the landscape through which America had spread its ideas of civilization. Despite its emptiness, the painting evokes an almost apocalyptic mood, suggesting that something is standing in opposition to the values that the artist has etched into its surface. Furthermore, a snake in the foreground lends the composition a Biblical flavour.

Fiercely the Red Sun Descending Burned His Way Along the Heavens

1875-1876

In this painting, the Great Lakes’ largest lake is depicted on the south shore of its shores. An approach popularised by Claude Lorrain and later associated with J.M.W. Turner dominates the composition, with a low-hanging sky filled with fiery reds, oranges, and yellows taking up the majority of the picture plane and dominating the overall look. Shockingly reddish waves below are illuminated by an orange glow cast by the sun on the water vapour in the atmosphere. This scene is punctuated by an archway of rock, surrounded by water and mist. Moran’s depiction of the strange New World would be enriched by the arch, which he used as a symbol of classical European architecture.

The Mountain of the Holy Cross

1875

An imagined viewer is placed at the bottom of a mountain river, where the strength and power of the water’s currents are depicted in the tree trunks that have been left vertical or upturned upstream, felled by the water’s currents. The zig-zagging valley, rocks, and trees fill the lower two-thirds of the canvas, making it dark, gloomy, and damp. It is the small rock face at the top of the painting that serves as the work’s symbolic centrepiece. The geological feature from which the work’s name is derived can clearly be seen through the mist and snow. Glacial snow and ice have formed a massive cruciform shape as a result of two rock cleaves.

The Three Tetons

1881

Moran’s subject is once again the splendour of the Rocky Mountains, specifically the distinctive Three Tetons, the Wyoming Range’s principal summits. Foreground grass and prairie wildflowers contribute to a more ‘pastoral’ mood than is achieved in many of his previous works even though the jagged mountains can be seen in the distance. For the first time, a Moran landscape appears suitable for human settlement, thanks to the presence of roaming cattle and a small encampment. As a result, the piece isn’t quite as eerie as its predecessors, but it does have a less ominous feel to it. The snow-covered mountains in the foreground and background gradually draw the viewer’s attention, but the white-cloudy sky above seems to subdue any sense of awe or terror they might otherwise elicit.

Grand Canyon (From Hermit Rim Road)

1912

As with Moran’s earlier paintings depicting the Grand Canyon, this piece conveys a sense of depth. ‘The Grand Canyon’ For the most part, the pines and rocks of the area are depicted with Moran’s famous scientific accuracy in the foreground, which is divided diagonally from the top right to the bottom left. However, the landscape abruptly disappears in the middle of the canvas, revealing the Canyon’s vast depths in an almost dizzying fashion. Blues, purples, and greys are used to depict the sky as it bleeds into the canyon where the Colorado River can be seen snaking away in the distance.

Answered Queries

Who is Thomas Moran?

An American painter and printmaker of the Hudson River School, Thomas Moran (February 12, 1837 – August 25, 1926) frequently depicted the Rocky Mountains in his work. After moving to New York with his family, Mary Nimmo Moran and her daughter Ruth, Moran found work as an artist.

What is Thomas Moran known for?

American painter and graphic artist Thomas Moran (1837-1926) was best known for his landscape paintings. It’s hard to miss the grandeur and immensity of the Far West in his enormous paintings.

Did Thomas Moran have kids?

Mary Nimmo Moran, an etcher and landscape painter from Scotland, was Moran’s wife. Two daughters and one son were born to the couple.

How Many Thomas Moran Paintings Exist?

80 Paintings of Thomas Morans exist.

Why did Thomas Moran paint Yellowstone?

Rather than a precise depiction of the landscape, his goal was to capture the awe-inspiring beauty of nature. The combination of Moran’s eye-catching use of light and dark, his sense of the drama nature can provide, and his enormous scene captivated the nation’s consciousness in a painting.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Thomas Cole’s signature style of spiritually-infused naturalism was adopted by the second generation of great American landscape painters, who adapted it to new landscapes.

- The Rocky Mountain School is often referred to as including Thomas Moran.

- Many of Moran’s contemporaries were inspired by J.M.W. Turner’s work.

- American popular culture is shaped by Moran’s depictions of the American West.

- He was instrumental in the creation of Yellowstone National Park, for example, thanks to his paintings of the area.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses