Born: 1535

Died: 1625

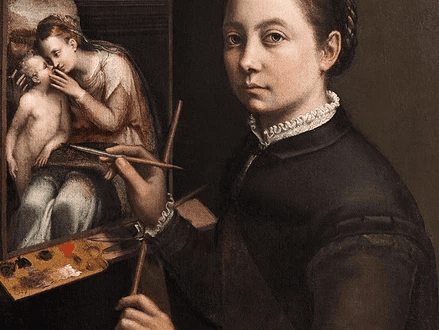

Summary of Sofonisba Anguissola

Sofonisba Anguissola was the first female artist of the Renaissance to gain worldwide recognition in her lifetime. She was able to create living, sophisticated pictures that were interesting and appealing both academically. She utilised self images to market and identify herself, and subsequently she used the same skill to produce official photographs of the Spanish royal family promoting her authority.

Her work was considered a work of art and she was praised as a natural marvel. However, these descriptions recognised her as a strange anomaly and catapulted her into fame. She was also recognised as devout, beautiful, a skilled conversationalist, a talented pianist and a compelling dancer; they all drew her to the Spanish and Italian aristocracies and did not jeopardise the social standards of women in their work. However, she exploited cultural limitations to her advantage, surpassed all expectations, and became one of her day’s most renowned portraitists.

In the 16th century, art theory picked up the interest of Italian artists, writers and collectors. The idea that art was about art was being formed. The pictures of Anguissola are more than simply depictions of the people she depicted. Many of her works reflect on the essence of art and invite the public to examine the artist-worker relationship.

In general, painting classes were reserved for artists’ sons and daughters throughout the whole Renaissance. The bulk of female artists worked in the studios of their families and just a few were recognised for their skills. These categories were not applicable to Anguissola. At a period when women artists were rare, she gained fame as a portrait painter. She and her sisters were pioneers in the arts, showing what women could accomplish.

For her to get compensated for her work, it would have been inappropriate since she was a noble lady. Her caretakers instead expressed gratitude by providing her marvellous presents. Even the portraits she created in Spain she did not sign. For these reasons, many of her works were subsequently assigned to male artists and most likely because she was a woman. The continuing process of reassignment is difficult and often controversial.

Childhood

Sofonisba was the eldest of six girls and a boy who was born into the little nobility. Sofonisba grew up under the careful care of her ambitious and intellectual father, in Cremona, northern Italian town under Spanish control at the time. Her parents, Amilcare and Bianca (born in Ponzone), gave her ancient Carthaginian name in order to emphasise her noble heritage, maybe due to their devotion to the Spanish monarch, as is customary with the Anguissola family. Amilcare also gave her a full humanist education, as was the practise in the Renaissance for all aristocratic children.

The classical education included Latin, ancient Greek and Roman literature, art and music, as well as contemporary humanist writers. However, those who met her considered her studies and drawing skills to be exceptional. Amilcare may have given this education above and above expectations to improve her chances of a favourable marriage in maturity – after all, he made such a beneficial marriage to Bianca, who was considerably more social in status than him. He intended to give Anguissola some independence, at least, as he did for the girls of many of his richest relatives.

The classical studies would have included Latin, ancient Greek, Roman literature, artworks and music, as well as contemporary humanist writers. However, those who met her considered her studies and painting skills to be simply remarkable. Amilcare may have given this education over and beyond expectations in order to improve its chances of a favourable marriage when she reached maturity. After all, he had married Bianca, who was considerably more advantageous than he, in social standing. At the very least, he intended to give Anguissola independence, as he did for many of the girls of his wealthy relatives.

Early Life

While aristocrats were expected to be highly educated in the arts, professionally pursuing them was unusual. Amilcare took a courageous step by organising professional painting instruction for Anguissola and Her sister Elena. In 1545 they became apprentices in the household of Bernardino Campi. Campi was a young Mannerist painter who met Giulio Romano when he was working at Mantua, and he was soon renowned for his exquisite work when he returned to Cremona. Anguissola learned in his studio to imitate famous painters like as Parmigianino, but she preferred to paint from life.

While it is impossible to tell how long Anguissola studied in Milan in 1549, she continued her studies with Bernardino Gatti (Il Sojaro). She became more acquainted with Correggio and Parmigianino’s painting methods under his tutelage and she acquired a predilection for everyday themes. Anguissola may also have collaborated on some of his works; the works she produced in the early 1550s show a spirit of creativity, one of her trademarks: imbuing portraiture with narrative and intellectual nuances.

This kind of composition has picked up the interest of Michelangelo Buonarroti, one of the Italian Renaissance’s most renowned masters. Although she doesn’t seem to have been apprenticed to him, she sent letters to him. Michelangelo offered her guidance and assessed her work to help her develop her painting skills. The teacher said that after having a drawing of a happy girl who taught an elderly lady how to read, an image of a crying child would be harder. Anguissola replied by giving him a Crawfish (1554) Boy Bitten which shows not only the love for Michelangelo’s drawing but also his sense of humour.

Asdrubale the baby brother of Anguissola is comforted by his younger sister, Minerva, in this moving picture, who smiles at the weeping youth. This painting influenced Caravaggio in the Baroque era to create his Boy Bitten a Lizard (1594-95).

Amilcare continued to promote Anguissola by bringing other brokers and artists in Northern Italy to Anguissola, publishing his skills and promoting its creative education. In 1556 Anguissola created a portrait of the famous miniaturist Giulio Clovio, thanking you for his advice. Her first accomplishment in this popular media may be seen in a little self-portrait painted the same year.

Mid Life

By 1559, her fame as a female portrait painter had passed beyond italy and King Philip II of Spain requested her to serve his young queen, Elisabeth of Valois as a lady-in-wait. During her stay at the Spanish court, Anguissola taught the queen in drawing and painting. At the request of Pope Pius IV, she also painted a portrait of the Queen, and numerous full-size and miniature portraits of the Spanish royalist and broker, inventing new ways in which she can formally show her subjects while preserving the lifelike quality of the Italian, the Spanish, art writers and collectors.

The painter and the queen became friends quickly. After her death in 1568, other Elisabeth entourage to France, but Anguissola stayed in Spain at the request of the king, Isabel Clara Eugenia and Catalina Micaela, to educate the newborn infants. In the meanwhile, Philip had Anguissola married a nobleman and gave her a great dowry, to guarantee her future and maybe to preserve her profession in painting. In 1571, she married Fabrizio de Moncada from Sicily, regent of Patern, and went back to his country of Sicily. Her marriage contract contained significant gifts for her paintings, which showed her great accomplishment in court.

Late Life

Nothing is known of Anguissola’s activity when she was married to Moncada, although she continued to paint and train others. When he died in 1579, she donated an altarpiece to a nearby church.

The artist then came back to Northern Italy, maybe closer to her family. Anguissola met the captain, Orazio Lomellino, and fell in love with him while on the Italian shore aboard a boat. Despite his nobility, the family did not approve of marriage (despite the involvement of the Duke of Florence, Francesco I de’ Medici). On the other side, King Philip granted her another rent year as a sign of his marital approval. The artist served as his agent in Genoa, offering art and artists for the new fortress of El Escorial.

For 35 years Anguissola lived in Genoa, where she maintained her renowned position. The commercial families of the city became richer and built splendid homes and commissioned works of art. She met and became familiar with two up-and-coming artists, Luca Cambiaso and Bernardo Castello. She created new images of grownup infants, who came to her to meet their own spouses in Savoy and Vienna, as well as dramatically illuminated religious pieces.

In 1615 Anguissola and Orazio moved to Palermo, where he performed his best. Many artists sought her help, just as they did in Genoa. She was unable to paint in her later years because of worsening vision. Despite this, she was a tremendous arts supporter, and throughout her careers she sponsored and helped other young artists. The year before her death in 1624, Anthony Van Dyck, a Dutch painter, made a visit to Anguissola. At the time he was just 24 years old, but he already had a fame in the world of art. He portrayed her in a delicate picture as a 92-year-old lady with a pale front, downward lips and sad eyes.

Despite her old age, van Dyck has stated that, despite her impaired vision, Anguissola was still intellectually bright. They spoke about the “true principles” of painting as he designed it, and van Dyck claimed that this discussion taught him more than anything else in his life about painting.

Since her early family photos, the work of Anguissola is imbued with narrative elements, elevating mundane, everyday occurrences to hilarious visual dramas. Her ability to convey a credible likeness full with the personality of the subject subsequently became one of the features of baroque portraiture.

Famous Art by Sofonisba Anguissola

Portrait of the Artist’s Sisters Playing Chess

1555

The Chess Game is perhaps Anguissola’s most well-known work, providing an intimate glimpse into the home, feminine world of sixteenth-century Italy. Three little girls may be seen in the foreground playing chess, while an older woman, possibly the Anguissola family’s maid, sits behind them and watches them play. Elena, the artist’s younger sister, sits on the left, calmly gazing at the spectator, her hands indicating that she has just vanquished her sister on the right. Minerva looks at the conqueror with wide lips, her hand outstretched in defeat and amazement. Europa, the youngest daughter, stands by Elena and gives a cheeky look to the dejected loser.

Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola

1559

Bernadino Campi, Anguissola’s first painting instructor, comes to loom out of the shadows in the gloomy creative studio. He has turned to make eye contact with the viewer over his shoulder as he paints a large-scale portrait of his pupil, Anguissola Anguissola, who is dressed in an elaborate, crimson gown with an open collar and gold trimming – a far more fashionable and expensive garment than the black gown she wears in many of her other self-portraits. This may be because Anguissola has been the subject of her own artwork for the first time. Anguissola prefers to portray herself as trendy and cheerful rather than the typical austere, studious, serious artist.

Self-portrait aged 78

1610

Anguissola has completed her life’s work in the same way that she began it – with a self-portrait. The artist is seated magnificently on a red velvet tasselled chair, a stark contrast to the gloomy, black clothes she wears in most of her self-portraits. She is seen at an easel with brushes and palettes in hand, playing a musical instrument, or carrying the symbols of her aristocratic lineage in early pictures, all of which are qualities she emphasised as a potential young courtier. She portrays herself as a woman of letters in this image.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Sofonisba Anguissola was the first female artist of the Renaissance to gain worldwide recognition in her lifetime.

- She was able to create living, sophisticated pictures that were interesting and appealing both academically.

- She utilised self images to market and identify herself, and subsequently she used the same skill to produce official photographs of the Spanish royal family promoting her authority.Her work was considered a work of art and she was praised as a natural marvel.

- However, these descriptions recognised her as a strange anomaly and catapulted her into fame.

- She was also recognised as devout, beautiful, a skilled conversationalist, a talented pianist and a compelling dancer; they all drew her to the Spanish and Italian aristocracies and did not jeopardise the social standards of women in their work.

- However, she exploited cultural limitations to her advantage, surpassed all expectations, and became one of her day’s most renowned portraitists.In the 16th century, art theory picked up the interest of Italian artists, writers and collectors.

- The idea that art was about art was being formed.

- The pictures of Anguissola are more than simply depictions of the people she depicted.

- At a period when women artists were rare, she gained fame as a portrait painter.

- Even the portraits she created in Spain she did not sign.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses