(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1923

Died: 1997

Summary of Roy Lichtenstein

In the early days of the American Pop art movement, Roy Lichtenstein was one of the most widely known and vilified artists. The breadth and depth of Lichtenstein’s early work demonstrated his deep familiarity with modernist painting; the artist would often insist that the abstract qualities of his images were just as important to him as their subject matter. Pop music critics were quick to accuse him of being twee and derivative when he finally arrived at his mature style in 1961 and was heavily influenced by comic strips. Because of the iconic nature of his work and the way he created it, which combined elements of mechanical reproduction with hand drawing, his name has become synonymous with Pop art.

Throughout the 20th century, art had made use of popular culture references, but Lichtenstein’s work appeared to be dominated by the styles, subjects, and reproduction methods found in popular culture. In contrast to Abstract Expressionism, Lichtenstein’s inspirations were drawn from the wider culture and did not reveal any personal feelings from the artist. This marked a major shift away from abstract expressionism.

Although Lichtenstein was accused of simply copying cartoons in the early 1960s, his process involved significant alterations to the original images. When it comes to discussing his work, the extent of those changes, and the artist’s rationale for making them, has long been a focus of debate.

When Lichtenstein used Ben-Day dots in his works, he highlighted one of Pop art’s central lessons: that all forms of communication, messages, and codes must be filtered by codes or languages. His early work, which drew inspiration from a wide range of modern painting, may have taught him to value codes. Even so, he went on to make works inspired by modern art masterpieces, in which he claimed that high and popular art are alike because they both rely on code.

Biography of Roy Lichtenstein

Childhood

Roy Fox Lichtenstein was raised by German-Jewish parents in New York City. Her mother Beatrice and her younger sister Renee lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan with their father Milton, a real estate broker, and mother Beatrice. A child, Lichtenstein enjoyed listening to science fiction radio shows, visiting the American Museum of Natural History, and building model planes. He started a jazz band in high school and studied watercolour painting at Parsons School of Design as a teen.

Early Life

While attending the Art Students League during the 1940s, Lichtenstein began studying painting with Reginald Marsh. This led to the creation of a body of work that is strikingly similar to Marsh’s social realist style. Following his graduation from Oberlin College, Lichtenstein enrolled at Ohio State University (OSU) to pursue a degree in fine arts while also taking classes in natural sciences and humanities. Portraits and still lifes influenced by Picasso and Braque are among his sculptural animal figures. Hoyt Leon Sherman, a professor at OSU who taught Lichtenstein the importance of “organised perception,” and his theories on the relationship between vision and perception, was a major influence on the artist’s later work.

Lichtenstein was conscripted into the military in 1943. He studied engineering at De Paul University in Chicago while serving his country. Additionally, he worked as both a stenographer and a draughtsman, enlarging army newspaper cartoons for the benefit of his superiors. As a result of his service in the military, he was able to see Europe as part of his travels. The artist returned to OSU in 1946 to finish his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree after being honourably discharged. The following year, he enrolled in the University’s graduate programme and began teaching art. Abstract Expressionism and biomorphic Surrealism were major influences on his work at this time.

After that, his work was shown in various galleries, including the Ten-Thirty Gallery in Cleveland, where he met the woman who would become his wife, Isabel Wilson, the gallery assistant. When his paintings had reached this point, he had begun using biomorphic shapes and a style reminiscent of Paul Klee’s Surrealism to depict musicians, street workers, and racecar drivers. After that, Lichtenstein turned to mediaeval themes like knights and dragons, as well as birds and insects painted in the same Surrealist style. It was at Carlebach Gallery in New York City in 1951 that Roy Lichtenstein began to cultivate a long-term fascination with a variety of media other than just two-dimensional paintings. He showed three-dimensional sculptures of kings and horses constructed from wood, metal, and a variety of found objects.

Mid Life

Lichtenstein began working in commercial engineering and drafting after moving to Cleveland with Isabel. During this period, he was working on a rotating easel that allowed him to paint from any angle, as well as cowboy and Native American themes. When it came to Lichtenstein, the method of working was more appealing: “Inverting or reversing the way I paint my own images is something I frequently do. The vast majority of them are a complete mystery to me… I’m not interested in the subject matter.” His work was first shown in New York in 1952 at the John Heller Gallery. As an instructor at SUNY Oswego in 1957, Lichtenstein drew inspiration from the Abstract Expressionist style with his thickly applied paint and abstracted imagery. Although he was influenced by the abstract expressionists, he began to incorporate figures into his canvases, such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, among others. In 1960, Lichtenstein became an assistant professor at Rutgers’ Douglass College, where he met Allan Kaprow. It was Kaprow who introduced Lichtenstein to a group of “happenings” artists that included Claes Oldenburg, Lucas Samara and Robert Watt, as well as George Segal and Robert Whitman. The collective created one-of-a-kind works of art that changed depending on the participation of the audience, but Lichtenstein was inspired by the group’s love of cartoons.

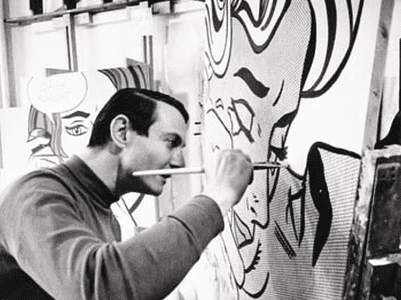

Lichtenstein first used Ben-Day dots, a commercial printing style for comic books or illustrations, to create contrasting colours in Look Mickey, his first cartoon in 1961. He later used this technique to define his style by exaggerating the dots in his paintings. When he was developing his technique in 1963, he combined aspects of hand-drawing and mechanical reproduction. He first hand-reproduced the panel from the cartoon, then projected the drawing using an opaque projector, traced it onto a canvas, then filled in the image with vibrant colours and stencilled Ben-Day dots.

With the help of Leo Castelli, a New York gallery owner, Lichtenstein’s reputation and income skyrocketed after a solo exhibition in 1962. Controversial: LIFE Magazine called him “one of the worst artists in America,” albeit in a tongue-in-cheek fashion, for his compositions that outraged some viewers. Despite this, Lichtenstein’s work was soon exhibited in major national exhibitions. His use of the Ben-Day dot technique in images of women and WWII combat scenes, such as in Drowning Girl (1963), was unabated throughout the 1960s. This collection of Lichtenstein’s cartoon-inspired paintings established him as an instantly recognisable Pop art figure, revered and derided for his challenges to traditional understandings of “fine art.”

Lichtenstein began producing large-scale murals in the mid-1960s, the first of which was created for the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, by the end of that decade. His use of Ben-Day dots and bold, solid colours also expanded to depict landscapes, such as yellow landscape in Lichtenstein’s Yellow Landscape series (1965). To reflect the artist’s continued interest in using media other than paint, such works included industrial materials such as Plexiglas, metal, and a shimmering plastic called Rowlux. Aside from ceramic sculptures and a series of paintings depicting cartoonish brushstrokes covering the canvas, Lichtenstein also experimented with ceramics and produced a series of paintings depicting large, cartoonish brushstrokes covering the canvas. Lichtenstein’s marriage to Dorothy Herzka and his divorce from Isabel also occurred during the 1960s.

Printmaking studio Gemini G.E.L. and Lichtenstein began a long-term collaboration in 1969 after Lichtenstein started producing prints in 1962 using the offset lithograph technique that was more commonly used in the commercial printing industry. While in Southampton in the 1970s, he was inspired by Modern masters to create still lifes and works of art with a variety of materials and textures. These large, painted bronze sculptures depicted everyday objects like lamps, pitchers and steaming coffee cups. Sculpture became an important focus during this time. In addition, Lichtenstein produced a series of works in which he used mirror imagery to suggest a space beyond the canvas, as well as abstract designs used in graphic art to represent mirrors.

Late Life

Lichtenstein’s work in the 1980s was influenced by a wide range of sources, including Surrealism, Cubism, and German Expressionism, and he used a variety of media to express his ideas. He moved back to Manhattan and opened a new studio, where he began to study both Abstract Expressionism and Geometric Abstraction. In the 1990s, he designed a series of home interiors based on advertisements in the Yellow Pages. In addition, he continued to produce large-scale paintings and sculptures for public display. National Medal of Arts was awarded to him back in 1995 The Roy Lichtenstein Foundation was established in 1999 following Lichtenstein’s death in 1997.

The Abstract Expressionists’ scepticism about commercial styles and subjects was shattered by Roy Lichtenstein’s work. Lichtenstein rose to prominence in Pop art as a leading figure by incorporating elements of “low” art, such as comic books and popular illustration. He is best known for his paintings of cartoons and comic books, but his career was prolific and somewhat eclectic, drawing from Cubism, Surrealism, and Expressionism as well as his own personal interests and influences. Postmodernism was greatly informed by Pop art’s reinterpretation of popular culture through the prism of tradition. This has remained an important influence on subsequent generations of artists.

Famous Art by Roy Lichtenstein

Popeye

1961

In the summer of 1961, Lichtenstein painted Popeye, one of the very first Pop paintings he made. At a later point in his career, he would turn to the more generic human characters of the time, but for the most part, he stuck with popular cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse and Popeye (here, Popeye appears with his rival Bluto). One of Lichtenstein’s final works in which he signed his name directly onto the picture surface, critic Michael Lobel has noted that he appears to have done so with increasing uncertainty in this piece; the open tin can above it also bears Lichtenstein’s signature. One of the most prevalent contemporary art criticism ideas is that art should have an immediate visual impact. Popeye’s punch may have been an ironic response to this idea. Lichtenstein here demonstrated that one could achieve this just as well by borrowing from low culture rather than abstract art.

Drowning Girl

1963

During the early 1960s, Lichtenstein became known as a leading Pop artist because of his paintings based on DC Comics. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns had previously incorporated popular imagery into their works, but Lichtenstein was the first to focus on cartoon imagery to the extent that he did. Pop art was born as a result of his and Andy Warhol’s work, and Abstract Expressionism as a dominant style was effectively put to rest. Instead of copying comic pages directly, Lichtenstein used an advanced technique that involved cropping images to create dramatic compositions, such as in Drowning Girl, which had the woman’s boyfriend standing on a boat above her. As he did with the comic book panels, Lichtenstein also condensed the text, reappropriating language as a symbol of commercial art and using it to challenge preconceived notions of what constitutes “high” art.

Yellow Landscape

1965

Lichtenstein experimented with a wide range of materials, including landscapes, to expand his use of bold colours and Ben-Day dots beyond the figurative imagery of comic book pages. Lichtenstein used motors, metal, and Rowlux, a plastic paper with a shimmery surface, in a number of collages and multi-media works. Lichtenstein demonstrated his knowledge of the history of art and suggested the closeness of high and low art forms by appropriating the traditional landscape motif and rendering it in his Pop idiom. Cézanne, Picasso, and Matisse are just some of the artists Lichtenstein drew inspiration from when creating his works.

Brushstrokes

1967

Since Lichtenstein was a prolific printmaker throughout the 1960s’ printmaking movement, his work was instrumental in the development of printmaking as an important art form. One of these prints, Brushstrokes, demonstrates his interest in the importance of the brushstroke in Abstract Expressionism. Painters like Lichtenstein, who disdained commercialism but painted in series, used recurring motifs in their brushstrokes to mock the Abstract Expressionists’ aspiration to convey feelings directly through brushstrokes. Lichtenstein’s brushstroke also suggests that the Abstract Expressionists may not have been immune to commercialism after all. “The real brushstrokes are just as pre-determined as the cartoon brushstrokes.” Lichtenstein has said.

House II

1966

Since Lichtenstein began painting murals for the 1964 World’s Fair in New York’s Queens, he has worked extensively on public and outdoor artworks, including paintings and sculpture. Buildings’ corners appear to move forward or backward in space, depending on where the viewer stands in relation to the large-scale sculpture House I. In spite of Lichtenstein’s tendency to employ flat colours and the fact that this sculpture is actually a flat piece of metal, the structure’s design lends a sense of volume. It’s possible to link his House sculptures to Lichtenstein’s interest in building interior design, which he explored in greater depth in the later works of his career.

Mirror I

1977

To Lichtenstein, cartoonists’ use of diagonal lines to denote a reflective surface was particularly intriguing. In his own words, “It’s as if you’re seeing a mirror, even though there are no such lines in reality. It’s an accepted practise that we don’t even think about.” Lichtenstein experimented with the graphic representation of reflection in earlier works, driven in part by an interest in the relationship between women and mirrors – both in historical artworks and contemporary culture – and the mirror became a recurring theme in his work in the 1970s. Reflection and reproduction are two themes that have fascinated artists since at least the Renaissance. Lichtenstein’s series may have been inspired by the appearance of mirrors in cartoons.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- In the early days of the American Pop art movement, Roy Lichtenstein was one of the most widely known and vilified artists.

- The breadth and depth of Lichtenstein’s early work demonstrated his deep familiarity with modernist painting; the artist would often insist that the abstract qualities of his images were just as important to him as their subject matter.

- Pop music critics were quick to accuse him of being twee and derivative when he finally arrived at his mature style in 1961 and was heavily influenced by comic strips.

- Because of the iconic nature of his work and the way he created it, which combined elements of mechanical reproduction with hand drawing, his name has become synonymous with Pop art.

- Throughout the 20th century, art had made use of popular culture references, but Lichtenstein’s work appeared to be dominated by the styles, subjects, and reproduction methods found in popular culture.

- In contrast to Abstract Expressionism, Lichtenstein’s inspirations were drawn from the wider culture and did not reveal any personal feelings from the artist.

- This marked a major shift away from abstract expressionism.

- Although Lichtenstein was accused of simply copying cartoons in the early 1960s, his process involved significant alterations to the original images.

- When it comes to discussing his work, the extent of those changes, and the artist’s rationale for making them, has long been a focus of debate.

- When Lichtenstein used Ben-Day dots in his works, he highlighted one of Pop art’s central lessons: that all forms of communication, messages, and codes must be filtered by codes or languages.

- His early work, which drew inspiration from a wide range of modern painting, may have taught him to value codes.

- Even so, he went on to make works inspired by modern art masterpieces, in which he claimed that high and popular art are alike because they both rely on code.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses