(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1925

Died: 2008

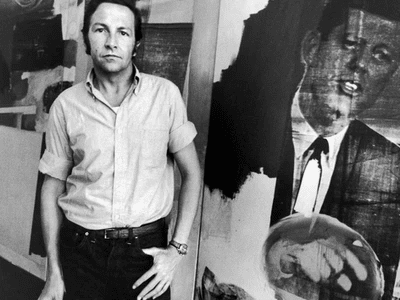

Summary of Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg was a pivotal player in the transition from Abstract Expressionism to succeeding contemporary movements, and is widely regarded as one of the most important American painters owing to his radical blending of materials and processes. His experimental approach to painting stretched conventional limitations of art, offering up areas of inquiry for future artists. He was one of the main Neo-Dada movement painters. Despite his status as the art world’s enfant terrible in the 1950s, Rauschenberg was highly regarded and revered by his forefathers. Despite his respect for them, he disagreed with many of their convictions and essentially obliterated their precedent in order to go on into new aesthetic terrain that echoed the previous Dada investigation into the idea of art.

Rauschenberg shifted from a conceptual outlook in which the authentic mark of the brushstroke described the artist’s inner world to a reflection on the contemporary world in which an interaction with popular media and mass-produced goods reflected a unique artistic vision, as he questioned the definition of a work of art and the role of the artist.

By integrating appropriated pictures and urban trash into regular wall paintings, Rauschenberg combined the realms of kitsch and fine art, utilising both traditional mediums and found items inside his “combines”

Painting, according to Rauschenberg, was connected to “both in terms of art and life Neither can be accomplished.” He produced artworks that travel between these domains in continual interaction with the audience, the surrounding world, and art history, based on this notion.

Rauschenberg preferred to leave his viewers’ interpretations to chance, allowing chance to dictate the placement and mix of the many discovered pictures and items in his artwork, so that there were no preconceived arrangements or meanings hidden within the pieces.

Childhood

Milton Ernest Rauschenberg was born in the tiny Texas industrial town of Port Arthur. Ernest, his father, worked for the Gulf State Utilities power business and was a stern and serious guy. Dora, his mother, was a devoted Christian who was very thrifty. She sewed the family’s clothing out of rags, which humiliated her son but may have inspired his subsequent collage and assemblage work. Rauschenberg sketched a lot and reproduced pictures from comic books, but his draughtsmanship was generally overlooked, with the exception of his younger sister Janet. He aspired to be a pastor until he was 13 years old, a prestigious position in his conservative society. Rauschenberg, a talented dancer himself, was discouraged from pursuing a career in the ministry after learning that his religion considered dancing to be a sin. For his high school graduation gift, he requested and got a store-bought shirt, his first in his life.

Early Life

Rauschenberg studied pharmacology at the University of Texas in Austin, but was dismissed after refusing to dissect a frog during his first year. The draught letter he received in 1943 spared him from having to tell his parents the bad news. He joined the Navy Hospital Corps and was stationed in a hospital in San Diego caring for war survivors after refusing to kill on the battlefield. While on leave, he visited the Huntington Art Gallery in California for the first time and viewed oil paintings in person. After the war, Rauschenberg wandered, ultimately enrolling in painting courses at the Kansas City Art Institute with the help of the G.I. Bill. When he initially arrived in Kansas City, he decided to give himself a new first name: Bob. The next year, the freshly minted Robert Rauschenberg went to the Academie Julian in Paris to study.

While in Paris, Rauschenberg met Susan Weil, a fellow American student, and the two became inseparable. After reading about and appreciating the discipline of its renowned director, Josef Albers, he saved up enough money and accompanied her to Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Albers, however, often and severely critiqued Rauschenberg’s work when he joined the institution. Albers’ materials course, in which pupils explored the line, texture, and colour of commonplace objects, impacted Rauschenberg’s later assemblages significantly. Rauschenberg and Weil remained at Black Mountain for the 1948-1949 academic year before moving to New York City, which Rauschenberg considered the art world’s core. They came at a critical juncture in the Abstract Expressionist movement. Rauschenberg and Weil married in June 1950, and their son Christopher was born in August 1951.

During the school year of 1951 and 1952, Rauschenberg divided his time between The Art Students League in New York and Black Mountain College, where he studied with professors Morris Kantor and Vaclav Vytlacil. His drive earned him a solo exhibition at New York’s Betty Parsons Gallery, where he displayed a series of White Paintings with scratched numerals and allegorical motifs (1953). At Black Mountain College, Rauschenberg resumed his white paintings by rolling white house paint onto canvas with a roller. The surroundings inspired the flat white canvases, which reflected shadows of people and the time of day. Jack Tworkov, a painter, also inspired him to experiment with black. Unlike the white series, his Black Paintings (1951) were textured with heavy paint and used newspaper shreds. Rauschenberg also encountered minimalist musician John Cage and dancer Merce Cunningham at Black Mountain College, where both taught and pushed for the use of chance techniques, discovered items, and ordinary, daily experiences in high art. All of these concepts had a significant impact on the young artist.

Mid Life

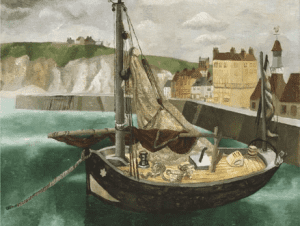

Weil filed for divorce and moved Christopher in with her parents when Rauschenberg returned to New York from Black Mountain in the autumn of 1952. Rauschenberg set off for Europe and North Africa with Cy Twombly, a fellow Art Students League student who went on to become a major Conceptual artist and with whom he was romantically engaged at the time. Rauschenberg’s earliest assemblages were created from trash he gathered in the Italian countryside during his travels. When he returned to the United States, he resumed his painting experiments with the Red series, which, like the Black series (1951), included a variety of surface textures and also used newspaper. From parasols to pieces of a man’s undershirt, Rauschenberg started to incorporate items in the surface of his paintings. These assemblages were dubbed “combines,” by Rauschenberg because they mixed paint and items (or sculpture) on the canvas.

In the winter of 1953, Rauschenberg met young painter Jasper Johns at a party, and the two became romantic and creative partners after many months of acquaintance. In 1955, Rauschenberg and Johns moved into the same building, and the two artists saw each other every day, sharing ideas and pushing each other to push the limits of art farther. Despite the fact that their styles were originally too dissimilar to create a really cohesive movement, their creative collaboration has been likened to that of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. Johns and Rauschenberg granted each other “permission to do what we wanted.” as Rauschenberg put it. Cage and Cunningham, who were both living in New York at the time, were good friends with the couple. The four painters had a similar mindset, which subsequent art historians dubbed the Neo-Dada style. They rejected Abstract Expressionist paintings’ coded psychology in favour of the spontaneous beauty of daily life. However, Rauschenberg’s strong friendship with Johns did not endure. In 1957, Johns was featured on the cover of Art News, and three of his paintings were purchased by the Museum of Modern Art. This rise to prominence strained Johns and Rauschenberg’s partnership, which ended in 1961, despite the fact that they had begun to drift apart in the late 1950s, with each artist working in studios outside of New York City. Regardless, Rauschenberg remained Cage and Cunningham’s buddy and partner.

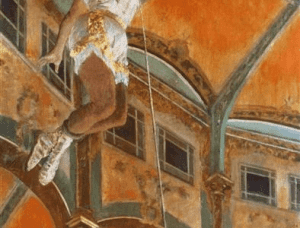

Rauschenberg’s career was characterised by collaboration. His passion for dancing led to a ten-year collaboration with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, as well as choreographers Paul Taylor and Trisha Brown, from 1954 to 1964. For Cunningham’s company, he designed costumes and scenery, while Cage provided the music. Throughout the 1960s, he choreographed and developed his own “theatre pieces” with other artists. In 1966, Rauschenberg and Billy Kluver of Bell Laboratories co-founded Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T. ), a non-profit organisation that promoted cooperation between engineers and artists. In 1962, Rauschenberg started working on lithographs with Tatyana Grosman, the printer and proprietor of Universal Limited Art Editions. Later, he worked with other printing studios, and in 1969, he purchased a property on Captiva Island that became the headquarters of Unlimited Press, a printmaking workshop that was open to both new and established artists.

Rauschenberg was quickly establishing himself as a major player in the art world. In 1963, he was honoured with a retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York, which was warmly received by critics and audiences alike. Following his meteoric rise in fame in the United States, he had an exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery and subsequently a solo show at the Venice Biennale, which he attended while on tour with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. In 1964, at the height of his career, he was given the Biennale’s first prize for painting, the first time an American had received this honour.

In the 1960s, Rauschenberg started to include imagery of space travel into his work, in line with his interest in current events and society. Dante is shown as an astronaut in A Modern Inferno (1965), an illustration made for Life Magazine in honour of Dante’s seven hundredth birthday. Rauschenberg used photos from NASA’s data in 33 lithographs in the Stoned Moon series (1969-70). Rauschenberg’s Spreads (1975-82) and Scales (1975-82) series signalled a return to assemblage in the 1970s (1977-81). He used silkscreen prints, magazine pictures, and ordinary items, but with more colour and on a bigger scale than in earlier works, using methods and imagery from his early works. Despite the fact that many works in this series sold to collectors, reviewers were unimpressed by what they saw as a retread of previous techniques. 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece (1981-98), a collaged artwork that evolved to be much longer than its title indicated, continuing Rauschenberg’s large-scale work.

In 1984, Rauschenberg founded the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange, combining his love of travel with his conviction that art can transform society (R.O.C.I.). In violation of then-current American Cold War policy, he went mainly to underdeveloped countries and Communist countries, studying craft techniques from the host country’s artists and craftsmen. Each of the twelve visits culminated in a large exhibition of Rauschenberg’s works that were influenced by the host nation. The trip came to a close with an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. While Rauschenberg developed relationships with artists throughout the world, domestic reviewers remained underwhelmed. The initiative was “at once altruistic and self-aggrandizing, modest and overbearing.” according to Roberta Smith of the New York Times.

Late Life

Rauschenberg had a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1990, which was followed by a smaller exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of his early work from the 1950s. His reputation as one of the world’s great artists was confirmed by the exhibits, which also highlighted the significance of his early work in the creation of contemporary American art. In 1992, the French government awarded Rauschenberg the Commandant of l’Ordre des Lettres, followed by the National Medal of the Arts in 1993. The artist went to the Betty Ford facility in 1996 to get help for his alcoholism, which had become worse in his latter years. He finished his recovery programme just in time for the inauguration of his six-year-long retrospective of 467 pieces at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1997-98.

Beginning in 2001, Rauschenberg had a succession of medical catastrophes, including a broken hip, an intestinal rupture, and a stroke in 2002 that immobilised his right side. Rauschenberg learnt to work with his left hand with the help of his carer and friend Darryl Pottorf. He worked until his death from heart failure on May 12, 2008.

Young artists who created subsequent contemporary trends were inspired by Rauschenberg’s work in the 1950s and 1960s. Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein attributed their Pop art inspiration to Rauschenberg’s collages of appropriated media images and silkscreen printing attempts. Rauschenberg’s Dada-based conviction that the artist had the power to define the meaning of art laid the groundwork for Conceptual art. The best example is his 1961 picture of Iris Clert, which included a telegram that said, “This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so/ Robert Rauschenberg.” It was created for a show at her gallery in Paris. Furthermore, occurrences and subsequent performances of the 1960s may be traced back to Rauschenberg’s work with John Cage in The Event at Black Mountain College (1952). Rauschenberg’s propensity for appropriating images from popular media and fine art inspired artists like Cindy Sherman and Sherrie Levine’s postmodern appropriation style. His predilection for bricolage inspired the use of non-traditional creative materials in the work of many subsequent artists, including land artists and feminist artists.

Famous Art by Robert Rauschenberg

White Paintings

1951

Rauschenberg’s White Paintings were an early formulation of the aesthetic principles that dominated his whole work, and were first regarded as a scandalous deception. The White Paintings are presently available in five distinct permutations of multi-paneled canvases, all of which are devoid of any trace of Rauschenberg’s touch. The pieces may be re-fabricated by his friends and helpers, including other artists from Cy Twombly to Brice Marden, by deleting any gesture. This lack of an authorial signature foreshadowed both Andy Warhol’s silkscreened works and Ad Reinhardt’s Abstract Paintings (1952–67), while also harkening back to older modernist works like Russian Constructivist Alexander Rodchenko’s monochrome paintings. The apparently empty canvases, uniformly covered with white house paint, serve as a background that comes alive with shadows as viewers approach, reflecting the light and noises of the space they inhabit. Thus, Rauschenberg simply permitted the White Paintings’ “subject matter” to change with each new audience and location, demonstrating his interest in aleatory, or chance, processes in art while simultaneously challenging the artist’s role in defining the meaning, or topic, of a piece of art.

Erased de Kooning Drawing

1953

Following the radical modernist precedent established by Marcel Duchamp’s earlier Dada readymades, Rauschenberg investigated the limits and definitions of art in the early 1950s. He set out to see whether erasure, or the erasing of a mark, could be considered a work of art with this “drawing,” He recognised that in order for the piece to succeed, he needed to start with a well-known piece of art. When young Rauschenberg requested Willem de Kooning for a sketch that he could erase, he was an established, leading figure in the New York art scene. De Kooning ultimately, though grudgingly, agreed to Rauschenberg’s proposal. By selecting a highly marked drawing packed with charcoal and pencil, he purposefully made Rauschenberg’s act of erasing difficult. The enormous job of erasing the drawing took Rauschenberg two months and hundreds of erasers; even when he completed, remnants of De Kooning’s work remained. Rauschenberg expressed his love for De Kooning by erasing his predecessor’s work, but he also indicated a departure from Abstract Expressionism. He framed the erased artwork in a simple, gilt frame with a mat that included an inscription written by Jasper Johns that explained the importance of the apparently empty page. The missing drawing is exhibited as an art piece, marking the act of erasing as fine art – a classic Neo-Dada act of challenging the meaning and significance of the art object.

Signs

1970

Rauschenberg produced this collage just after the turbulence of the 1960s came to an end, encapsulating the decade’s upheaval. While the excitement and hope of the 1969 moon landing were represented in the picture of astronaut Buzz Aldrin in the bottom left corner, Rauschenberg encircled this figure with a constellation of images that also signified the turbulence of the previous decade. The assassinations of John F. Kennedy in 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, and Robert, or Bobby, Kennedy in 1968 all emphasised the loss of political hope in the 1960s. The top right picture of Janis Joplin, a Port Arthur, Texas native, highlighted the loss of youthful potential in the music business as rock stars drank themselves to death; Joplin died of an overdose in October 1970, just before Rauschenberg produced the print. Other pictures in the vicinity of the astronaut include urban violence, the Vietnam War, and a peace vigil, all of which are depictions of the turbulent 1960s. The collage structure and overall composition add to and represent the turmoil of the time period.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Robert Rauschenberg was a pivotal player in the transition from Abstract Expressionism to succeeding contemporary movements, and is widely regarded as one of the most important American painters owing to his radical blending of materials and processes.

- His experimental approach to painting stretched conventional limitations of art, offering up areas of inquiry for future artists.

- He was one of the main Neo-Dada movement painters.

- Despite his status as the art world’s enfant terrible in the 1950s, Rauschenberg was highly regarded and revered by his forefathers.

- Despite his respect for them, he disagreed with many of their convictions and essentially obliterated their precedent in order to go on into new aesthetic terrain that echoed the previous Dada investigation into the idea of art.Rauschenberg shifted from a conceptual outlook in which the authentic mark of the brushstroke described the artist’s inner world to a reflection on the contemporary world in which an interaction with popular media and mass-produced goods reflected a unique artistic vision, as he questioned the definition of a work of art and the role of the artist.By integrating appropriated pictures and urban trash into regular wall paintings, Rauschenberg combined the realms of kitsch and fine art, utilising both traditional mediums and found items inside his “combines”Painting, according to Rauschenberg, was connected to “both in terms of art and life Neither can be accomplished.”

- He produced artworks that travel between these domains in continual interaction with the audience, the surrounding world, and art history, based on this notion.Rauschenberg preferred to leave his viewers’ interpretations to chance, allowing chance to dictate the placement and mix of the many discovered pictures and items in his artwork, so that there were no preconceived arrangements or meanings hidden within the pieces.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses