(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

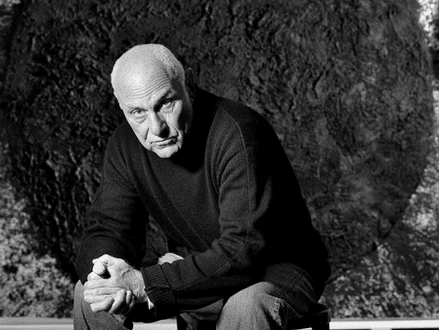

Born: 1938

Summary of Richard Serra

Richard Serra is considered to be one of the most significant American sculptors post-Abstract. From the late 1960’s until now, his work was critical in promoting the contemporary heritage of abstract sculpture following minimalism. His work provides new and broader attention to tactile and visual options for viewers, usually in a particular place, if not very public.

Serra has inherited and expanded the abstract sculpture heritage, adapting the welded steel medium (the Cubism of the early twentieth century, initially a concern) to new holistic ideals from the 1960s and 1970s. Growed under the umbrella of great artists such as Constantin Brancusi, Pablo Picasso and Julio González, Serra both inherited and advanced the abstract sculpture tradition, adapting the sculpture medium (initially an issue of the Cubism of the early 20th century) to More contemporary minimalistic artists like Donald Judd and Carl Andre, have shown how sculpture and its materials can stand by themselves and not by themselves.

Serra revived that contemporary heritage, which indicated that the human body had no place in painting or sculpture any more, and re-established a portion of human grandeur. He looked at how an artwork could be closely connected to a certain setting, how a visual and physical relationship could be established with a viewer, and how it could create rooms (or environments) in which a viewer could experience universal qualities such as weight, gravity, agility and even meditation.

Serra’s capacity for cooperation with, or learning from, contemporary musicians, dancers and videographers was part of an era of american art when artists explored more and more diverse fields of art, which overlap and share their concerns with a new type of art, which could lead the viewer’s experience to a fully physical or incarnate experience beyond purely visual and optical acts. Serra’s work consists of a painting, a sculpture, an architectural piece and an epic component of the modern industry.

The concern of Serra over the implicated relation between the conception of his sculpture and its intended location has given rise to a new (sometimes heated) international debate on the role and governance of art in public areas like city parks, corporate squares and memorial sights where art works can virtually interrupt daily routines for viewers in ways not necessary. Serra’s sculpture definitely suggests that art in contemporary society ought not to be a cloistered museum setting but “participatory” that is, a gesture or a body’s insertion into everyday life.

Some feminist historians have seen Serra’s materials and techniques, including large-scale steel panels and soldering, as “last gasp” of the so-called masculine concepts and artist practises of Abstract Expressionism. As a consequence, subsequent generations inadvertently generated a range of reactions, artists moving towards more temporary, ordinary materials in the late seventies and eighties to suggest that art may be immense without depending on huge, “in your face” forms and components.

Childhood

Richard Serra was a Russian Jewish woman’s second son and a Spaniard. He grew up with his family in the middle of the sand dunes of San Francisco. He didn’t know much beyond the world, let alone the great arts, since he remained mainly inside the limits of his home life. His earliest creative spurts inspired the time spent in the shipyards, where his father worked as a pipefitter.

Serra says that on his fourth birthday, at his launch at the Marine Shipyard in San Francisco, the roots of his art were planted: “All the raw material I needed is contained in the reserve of this memory.” He remembered the boat’s significant horizontal curvature later in adulthood as well as its contradictory lightness and speed as the craft raced through the seas. At around the same time Serra started sketching an activity that he felt helped improve his imagination and feeling of creativity and gave him confidence to build his artistic ability.

Early Life

Serra graduated in English Literature from the University of California in Santa Barbara in 1961. He supported himself throughout his studies by working in a steel mill, a job which would afterwards influence his work as an artist. Serra studied painting at Yale University with contemporaries Brice Marden, Chuck Close and others, whom he mostly remembers as “more advanced” students. Serra studied in Paris in 1964-65, where he worked in a copy of Brancusi’s studio for a lot of time.

The next year, Serra went to Italy and started to paint a series of grids in a number of colours. Serra finally left behind after discovering from a recent Art News issue that Ellsworth Kelly painted in a similar way. Serra realised that he was unhappy with the two-dimensional borders of painting after viewing Las Meninas of Velásquez on a side trip to Spain. Serra’s artistic career almost flipped upside down as a consequence of the event; in his quest for a new route he started to work with living animals in cages and in some instances filled them.

Mid Life

Serra immigrated to the United States in 1966 and resided in New York where it started to produce its first rubber sculptures, which Jackson Pollocks painting, Mural, claims to have inspired (1943). From 1968 to 1970, Serra produced a series of Splash consisting of semi-sculption works formed by pouring molten plumage over the spatial junction, or a gutter, in where the vertical studio wall met the horizontal floor plan. Critics rapidly classified Serra’s “gutter” works as well as those of contemporaries whose work also underlined the confluence of action, environment and medium in the form of process art.

The following Prop series, which Serra started in 1969, is a precursor of the gigantic metal works he is widely known today. Serra’s memory of his childhood recollections of an oil tanker skimming the sea’s surface is presumably the source of the Props.

In 1970, Serra helped a friend and artist Robert Smithson to create the environmental work of Spiral Jetty. In this instance, Serra’s exposure to environmental art reinforced the idea of location specificity or the phenomena of a work of art as an element in its surroundings (this had been implied, if subtly, in the Splash series). Serra’s interest with the spaces created (or otherwise emphasised) by the art piece itself and the physical and visual link between the artwork and the spectator increased as he worked in larger sizes.

Such and other themes may still be found now in Serra’s work. Although Serra distinguishes himself from the “heroic” stance of pioneers in modernist sculptural art such as Pablo Picasso, Julio González and David Smith, most of his latest large-scale pieces are made of cor-ten steel.

In the late 1960s, Serra started experimenting with video art and in 1968 released his first video art piece Hand Catching Lead. Hand shows the artist trying to catch pieces of lead falling from the top of the frame. Serra sees his films as “a supplement to understanding his sculpture,” and has subsequently produced a number of other works that incorporate metal, especially steel in his favourite mediums.

Serra also worked in music and dance in New York during his early years. Serra performed and installed in collaboration with Yvonne Rainer, Stephen Reich and Joan Jonas, acknowledging that the concepts of space and balance in the work of music and dance are similar to his own in sculpture. Serra is referenced in the song White Sky of Vampire Weekend and his work is featured as a tribute to his musical background on the cover for the album ‘Sunn O) Monoliths’ & Dimensions.

The public installation of Tilted Arc of Serra at the bottom of Manhattan’s Federal Plaza in 1981 led to a civil controversy that was an infamous footnote in the career of Serra. The installation of the commission triggered a raw, angry response by local officials, who saw Tilted Arc as little more than an unstoppable monster that would draw graffiti and trash.

The increasing protests against Tilted Arc have attracted so much worldwide attention that the municipal administration has had to conduct a series of public hearings on this issue, in which Serra stated that “to remove the work is to destroy it.” The incident triggered a wider worldwide debate about contemporary art in public spaces and popular opinion, or the lack of it. In fact, the court ordered Titled Arc to be permanently deleted from its site following the hearings. Serra sought an appeal, but it had no immediate effect. In 1989, the sculpture was dismantled and removed from Federal Plaza.

Serra is generally considered as one of the most significant sculptors of the late 20th century. Serra, a leading contemporary Renaissance man, has inspired tens of thousands of artists through his long career in painting, sculpture, music, dance, film, performance and installation art. Architects and urban planners today often acknowledge Serra’s impact, which he disregards since real art is never, as he thinks, utilitarian. As Tilted Arc shows eloquently, Serra’s work is hard to ignore, and has played a crucial role in highlighting the debate on public art.

Serra’s work inspired the development of a public art programme (in the birthplace of San Francisco) at the University of California and helped build sculpture parks all across California.

Famous Art by Richard Serra

Gutter Corner Splash: Late Shift

1969-1995

Gutter Corner Splash is Serra’s first work in metal sculpture, and it shows him exploring with the medium’s many characteristics. Serra has said that the Splash series evolved out of his interest in an implicit, reciprocal interaction between the artist, the piece of art, and the eventual viewer: “I was interested in my ability to move in relation to material and have that material move me.”

Tilted Arc

1981

Tilted Arc, according to its detractors, caused pedestrians to go around rather than directly across Federal Plaza in the heart of New York City’s commercial area (where indeed global powerbrokers are accustomed to walking in very straight, or goal-oriented trajectories). Tilted Arc is, without a doubt, Serra’s most effective (though eventually publically reviled) representation of his underlying goal to include direct audience engagement in the sculptural experience, or his work as an unavoidable material and visual “phenomenon.”

Torqued Ellipse

1996

Serra sees his Torqued Ellipse series as a natural conclusion to the architectural difficulties, or, as it were, visual irresolution, offered by Francesco Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane [Church of Saint Charles at the Four Fountains], a Roman Catholic church from the Baroque era (1599-1667). Although the church’s dynamic, undulating front is echoed in Snake’s bending walls, the latter’s enveloping curves represent the artist’s attainment of security and tranquilly after pondering his predecessor’s statement of restless spiritual aspiration in Travertine limestone for so long.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Richard Serra is regarded as one of the most important post-Abstract Expressionist American sculptors.

- From the late 1960s to the present, his work has been crucial in furthering the modern abstract sculpture tradition in the aftermath of Minimalism.

- His work brings fresh, wider attention to sculpture’s tactile and visual possibilities for spectators to experience, typically in a site-specific, if not extremely public location.

- Serra inherited and advanced the tradition of abstract sculpture, adapting the medium of welded steel (originally a concern of early-20th-century Cubism) to new, holistic values of the 1960s and 1970s.

- Growing up in the shadow of greats like Constantin Brancusi, Pablo Picasso, and Julio González, Serra both inherited and advanced the tradition of abstract sculpture, adapting the medium of welded steel (originally a concern of early-20th-century Cubism) to More contemporary Minimalist artists, such as Donald Judd and Carl Andre, showed how sculpture and its materials may stand alone, rather from being obliged to act as vehicles for interpreting an artist’s emotional and intellectual life.

- Serra resurrected that modern legacy, which suggested that the human body no longer had a place in painting or sculpture, and restored part of the human body’s majesty to it.

- He looked at how an art work could be intimately related to a particular setting, how it could take on a physical as well as a visual relationship with a viewer, and how it could create spaces (or environments) in which a viewer could experience universal qualities like weight, gravity, agility, and even meditative repose.

- Serra’s work is a painting, a sculpture, an architectural piece, and an epic part of contemporary industry all rolled into one.

- Some feminist historians have viewed Serra’s materials and methods, such as large-scale steel panels and welding, as a “last gasp” of Abstract Expressionism’s so-called male ideas and artistic processes.

- As a result of his work, following generations have unintentionally spawned a slew of counter-responses, with artists turning to more transitory, commonplace materials in the late 1970s and 1980s to imply that art might be enormous without relying on large, “in your face” ingredients and formats.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses