(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

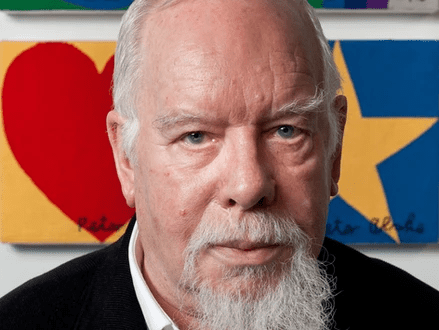

Born: 1932

Summary of Peter Blake

When it comes to British Pop art, Peter Blake is generally referred to as the “Godfather of British Pop art.” Like many other artists of his generation, he grew up in a country still reeling from World War II, and as a result, a lot of his interests were sparked by the burgeoning American advertising industry’s use of groundbreaking new methods like screen-printing to produce upbeat and daring depictions of life in magazines, posters, and billboards. Due to his early design background and a solid grounding in older historical types of art, his fascination with the young popular culture and the London pop music scene in swinging London merged with historical art influences to create an urban realism that was uniquely his own. Pop art broke down boundaries between conventional fine art and the cutting edge realm of Pop art, upending the established order’s view of what constituted art. With each step forward in his career, the artist produced work that paid homage to the past while also looking to the future, representing man’s continuing experience of being susceptible to the effects of the present and the future.

Many of Blake’s best-known works are collages of images inside pictures that are all painted on the same flat surface. Whatever the medium, Blake shows us our common trait of collecting visuals and using them to assimilate into badges of our own personal identity, where the line between looking and adopting becomes blurred. Blake’s work can be found pinning images to clothing, framing them on walls, or holding them up by characters within compositions.

Blake’s work often dealt with the invasion of popular culture, particularly pop music, into the art world scene. The work he made for The Beatles’ landmark Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover is the most recognised example of this genre crossover.

For Blake, the striving for a better present or future was uniquely British. This quest manifested itself in his Pop art as the idealistic spirit seen in American commercials and popular culture. The nostalgic portrayals of a more conservative and Victorian past, as well as mythical realms like elves and fairy tales, can be seen in his later Ruralist works. This may be seen in his landscape paintings, as he depicts the softer aspects of rural life.

These connections to contemporary cultural trends in Blake’s work comment on the human condition in the face of a never-ending stream of outside influences, especially in today’s media-saturated world. Wrestlers, singers, celebrities, literary works, and allusions to earlier works are all examples of how he pays respect to the mythmaking resources that have shaped our contemporary worldview.

According to something Blake once said, “The history of art is very necessary if you want to produce art. Ask any artist and they will all acknowledge that they have learnt from earlier works of art. Maybe I do it better than others since I often steal and quote from works of art.” At the end of his career, he continued to sprinkle his work with allusions to the past and present, implying that they were still connected.

Childhood

Peter Blake was born in Kent, England, the son of an electrician, and grew up in a normal working-class neighbourhood. For him, being “a solitary child” and being “extremely shy” were not mutually exclusive experiences, even if he had younger brothers and sisters. When his family was forced to flee during World War II, he lost time in school.

Gravesend Technical College Junior Art School was his first art school stop when he was 14 years old. There he acquired creative basics including how to do a life drawing, typography, and carpentry. Fine art and classical music were presented to him for the first time when he was living there. However, he never forgot his working-class origins, and he continued to attend jazz clubs, play football, speedway, and wrestle, and he remained close to his mother and aunt throughout his adult life.

Blake’s appearance was drastically altered after a major bike accident when he was 17 years old. I knocked out four teeth and had 35 stitches – my mother didn’t know me when she got to the hospital,” he says. Eventually, he grew a beard to cover up his wounds, and he’s kept it ever since.

Early Life

Blake was a graphic designer when he first applied to the Royal College of Art. He just had to submit one painting as part of his portfolio in order to get admitted into the painting programme instead of the drawing one. Ruskin Spear, an artist whose Dada-inspired work made use of everyday materials Blake referred to as “proto-pop” taught him at the RCA. As a result, Blake became more interested in popular culture as a source of inspiration for his paintings. After discovering he could paint wrestlers and strippers, he continued to do so until approximately 1954.

When he was an undergraduate at the RCA, he researched and completed a dissertation on music hall nudity. Music halls were losing popularity by the middle of the 1950s, so performers sought to attract more people by doing shows with nude women. These ladies were not permitted to move and instead had to remain still for the duration of the play.

Blake received a one-year travel scholarship at the conclusion of his academic career. He points out that whereas most individuals utilised this time to research traditional artworks or phenomena like “the light on north Italian chapels” he went off the rails and instead focused on popular art. Blake went to bullfights, football, and wrestling instead of museums, and he even spent a few weeks with the circus.

A few years after moving back home in 1957, Blake found employment as an art teacher where he could devote more time to honing his skills and creating new work.

Mid Life

Blake started to mingle with the people who would later develop Pop art, like Andy Warhol. In 1958, he was invited to a dinner party thrown by art critic and Independent Group founder Lawrence Alloway, who was also a member of the Institute of Contemporary Art in London’s developing British Pop art scene. Alloway was one of the first persons to adopt the phrase “Pop art” in reaction to Blake’s remark about his creative aims.

Blake was included in London’s Whitechapel Gallery’s “Young Contemporaries” exhibition in 1961. Blake’s work was presented with David Hockney’s and RB Kitaj’s, which helped begin the careers of numerous younger members of the Pop art movement. His art appeared in the inaugural Sunday Times colour supplement after he was awarded the John Moores Award that year.

Even though Blake’s work was already well-known in the art world at this time, he was first presented to the general audience on the BBC television show “Pop Goes the Easel” in 1962.

Robert Fraser, a prominent art dealer who was subsequently imprisoned with Mick Jagger for cocaine possession, represented Blake when he signed him up in 1963. In this way, Blake became one of the most important personalities in 1960s London’s thriving swing scene, together with other prominent individuals from the world of popular culture. Fraser was the one who brought Blake to Paul McCartney and suggested him for the legendary Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover design. Fraser presented Blake to Paul. Aside from getting his work in front of a worldwide audience, this event paid him just £200 and gave him no copyright or royalties on the final cover.

After Fraser’s gallery closed in the late 1960s, Blake and his wife, fellow artist Jann Haworth, relocated to Wellow, Avon (a tiny town near Bath) in 1963. The Ruralists, an art collective he founded there, painted in a more realistic manner. Blake earned a lot of bad press once he moved away from the city’s chaos and innovation. Blake produced a large number of works depicting myth and fantasy during this time period, many of which included fairies. Along with fellow artist Graham Ovenden, he drew Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass. He was only here for a short period of time before his wife filed for a divorce since she had started seeing someone else. Blake’s separation from his first wife Jann, with whom he had two kids, was a wrench in his life. He returned to London, where he met Chrissy Wilson, his second wife.

When Blake moved to London, his personal and professional lives began to flourish once again. In Los Angeles, he met up with fellow artist David Hockney, who encouraged him to go back and rediscover collage methods from his earlier work as well as more contemporary subject matter. In 1981, he was elected as a fellow of the Royal Academy of Arts in the United Kingdom.

Blake had a residence at the National Gallery in London in the 1990s. This was a critical juncture in both his artistic development and his personal life. “every day when the museum closed and the guards had gone, I’d spend an hour or so wandering around on my own.” he recounted later.

Late Life

As the art business became more competitive and obsessional, Blake expressed his desire to retire in 1997. He’s still creating art now, whether it’s by drawing, painting, or using other mediums.

When it came to defining his late time, Blake was unusual among artists since he wanted to include everything from the late 1990s to now. This phrase was invented by him: “a period in which artists are free to accomplish anything they choose. If you don’t want it to, it doesn’t have to be connected to your previous work, and that independence is liberating. While it’s customary for others to select when your Late Period begins or ends, I made the intentional decision to have mine now rather than wait for anybody else.”

He’s still working a lot, and it’s usually on collaboration or design projects. Like designing textiles for Stella McCartney, he also painted Queen Elizabeth II and created album covers for bands like Oasis and Band Aid. In addition, he has been working on illustrating Dylan Thomas’ play Under Milk Wood for the last 10 years.

For his contributions to art, he was knighted in 2002, an honour of which he is quite proud.

Many Pop artists, such as American Pop artist Andy Warhol, were influenced by Blake, including them. He is also a supporter of the so-called “Young British Artists” of the 1990s. Many of them consider him a friend, and he has often championed their work. I prefer to think of myself as part of the group that stands behind the YBAs today,’ he remarked. In the same way that Blake’s earlier Self Portrait with Badges exposes the grittier and less chronicled aspect of youth, his influence may be seen in their stealing of popular culture and exposing it (1961).

Famous Art by Peter Blake

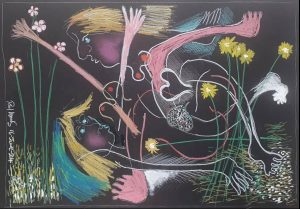

On the Balcony

1956-1957

There are several allusions to Blake’s renowned poem “On the Balcony.” throughout this well-known artwork. In museums and galleries, art may be discovered as well as in transitory periodicals and pictures. a copy of The Balcony by Eduard Manet (1868) is held by the person on the left, while a copy of LIFE magazine hides the face of another person (in all, approximately 32 versions of images of balconies are in the image). Pop art’s core ideas, such as the disintegration of conventional understandings of art object and source, and the rethinking of the line between art and life, may be observed in the young figures, who look to be teens. For this reason, we may deduce that Blake’s provocative invitation to see everything around us as worthy works of art is conveyed by the way the painting’s allusions are shown as an unified whole, accompanied by individuals with the wide-eyed gaze of youth. Throughout the 1950s, Blake created several photographs of young people and children that were cropped closely and featured their faces directly in the camera. Face profiles, which are thought to be more nuanced, are preferred over straight head-on glances.

Girlie Door

1959

To make Girlie Door, Blake took inspiration from a popular adolescent boy’s bedroom setting. Painting a hardwood foundation red, the hue of unfulfilled teenage longing, on which are glued an assortment of gorgeous ladies from the big screen, gives the piece its door-like appearance. Sophia Loren flirtatiously sniffs a flower, as Marilyn Monroe bares her enormous genitals below her. The ladies drool and pose for the camera, their gaze fixed on the spectator. The doorknob serves as a shadowy invitation to “open me.” Considering that Blake’s early life was disrupted by war, and that an injury sustained in a bike accident permanently altered his perception of his physical appearance, it’s possible that this poem represents the suppressed libido of an outsider. An accessible shrine of women from popular culture at the period is reflected in the work, as are the usual intrigues of an adolescent lad who longs from the safety of his own seclusion. However, it also represents an impediment to entering that world since it is barred from entry in a prohibitive manner.

Self-Portrait with Badges

1961

With this self-portrait, Blake portrays himself as an impressionable young man shaped by his adoration for American pop culture. There are several insignia on his uniform and he has a downcast look on his face. He is wearing trendy Converse sneakers and turned-up pants. Badges on the artist’s clothing show he’s attempting to establish an identity by connecting himself with as many causes and iconic symbols as possible in the hopes of landing on one that will stay. However, the initiative seems to be a failure, given the badges favour an unpopular American presidential candidate, Elvis Presley, and Pepsi (Coca Cola’s less successful competitor).

The First Real Target

1961

American painters such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns influenced Blake’s style, and he responded to them with his own work. It makes specific reference to Johns’ and Kenneth Noland’s paintings of targets. A lot of these pieces portrayed the subject as a piece of pop culture memorabilia, and they did it by recycling previously unutilized images. Because of Johns’ use of well-known images like the target in his work, his audience members were able to enjoy the art on “other levels” that were not immediately apparent to those seeing it.

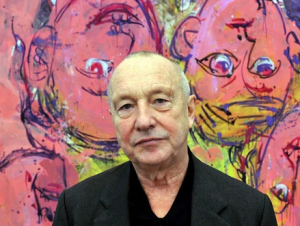

Doktor K Tortur

1965

Blake painted and printed screen prints of wrestlers throughout his career, including this one. When he was younger, he started attending to wrestling bouts and became attracted by the resulting culture and environment. In order to create a more terrifying character, this wrestler claimed to be German while in the ring, which is how I got the idea for this painting. Blake was drawn to wrestling events because of its performative and campy aspect, and he wanted to capture that in his artwork.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band Album Cover

1967

For decades, many have regarded the Beatles’ 1967 album cover for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as a symbol of 1960s psychedelic culture. Blake’s most well-known and widely-reproduced piece. However, he received a pittance of £200 for his work, and as a condition of receiving it, he had to waive all copyright and royalty rights (an occurrence that he remains bitter about to this day). With the Beatles posed in life-sized reproductions of 70 renowned persons, from pop culture icons to sports stars to intellectual figures, the cover was conceived as a live collage. All of the well-known figures on the cover seem to be squeezing through the throng to get a better view of The Beatles in the front.

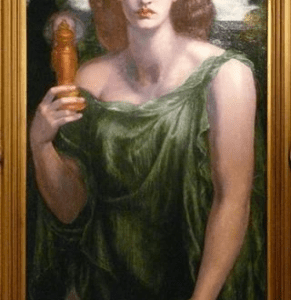

Puck, Peaseblossom, Cobweb, Moth and Mustardseed

1969-1984

When Peter Blake relocated to the countryside in the late 1960s, he began painting in a completely new way. Instead of concentrating on the bright colours and commercial items of Pop art, he drew inspiration from the countryside and an antiquated way of life. Blake drew heavily on the Victorians’ fascination with fairies and fairy tales while creating this piece. The fairies who attend on Queen Titania and King Oberon were his subject matter of choice, as were many Victorians who had a soft spot for fairy tales.

The Meeting, or Have a Nice Day Mr. Hockney

1981-1983

A meeting between three artists is shown in this artwork, including Peter Blake (centre) and British artists Howard Hodgkin and David Hockney (left and right respectively). Following their 1979 visit to Hockney’s Los Angeles house, Blake launched the project, demonstrating the relationship between the two artists. Hodgkin and Blake decided to collaborate on three paintings, each to be shown in an L.A.-style gallery, and to make three works each. To some extent, the painting is an effort to provide permanence to a passing moment. It exhibits Blake’s ability to paint in a realism manner while using Renaissance laws of perspective.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- When it comes to British Pop art, Peter Blake is generally referred to as the “Godfather of British Pop art.”

- Like many other artists of his generation, he grew up in a country still reeling from World War II, and as a result, a lot of his interests were sparked by the burgeoning American advertising industry’s use of groundbreaking new methods like screen-printing to produce upbeat and daring depictions of life in magazines, posters, and billboards.

- Due to his early design background and a solid grounding in older historical types of art, his fascination with the young popular culture and the London pop music scene in swinging London merged with historical art influences to create an urban realism that was uniquely his own.

- Pop art broke down boundaries between conventional fine art and the cutting edge realm of Pop art, upending the established order’s view of what constituted art.

- With each step forward in his career, the artist produced work that paid homage to the past while also looking to the future, representing man’s continuing experience of being susceptible to the effects of the present and the future.

- Many of Blake’s best-known works are collages of images inside pictures that are all painted on the same flat surface.

- Whatever the medium, Blake shows us our common trait of collecting visuals and using them to assimilate into badges of our own personal identity, where the line between looking and adopting becomes blurred.

- Blake’s work can be found pinning images to clothing, framing them on walls, or holding them up by characters within compositions.

- Blake’s work often dealt with the invasion of popular culture, particularly pop music, into the art world scene.

- The work he made for The Beatles’ landmark Sgt.

- Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover is the most recognised example of this genre crossover.

- For Blake, the striving for a better present or future was uniquely British.

- This quest manifested itself in his Pop art as the idealistic spirit seen in American commercials and popular culture.

- The nostalgic portrayals of a more conservative and Victorian past, as well as mythical realms like elves and fairy tales, can be seen in his later Ruralist works.

- This may be seen in his landscape paintings, as he depicts the softer aspects of rural life.

- These connections to contemporary cultural trends in Blake’s work comment on the human condition in the face of a never-ending stream of outside influences, especially in today’s media-saturated world.

- Wrestlers, singers, celebrities, literary works, and allusions to earlier works are all examples of how he pays respect to the mythmaking resources that have shaped our contemporary worldview.

- According to something Blake once said, “The history of art is very necessary if you want to produce art.

- Ask any artist and they will all acknowledge that they have learnt from earlier works of art.

- Maybe I do it better than others since I often steal and quote from works of art.”

- At the end of his career, he continued to sprinkle his work with allusions to the past and present, implying that they were still connected.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses