(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1960

Died: 1988

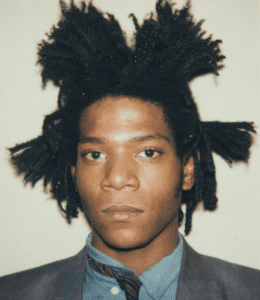

Summary of Jean-Michel Basquiat

In just the brief years of his career, Jean-Michel Basquiat went from a graffiti artist to a downtown punk scenester to a famous art star. This vertiginous upsurge led me from sleeping on New York City streets to becoming friendly with Andy Warhol and joining the elite American art scene as one of neo-most Expressionism’s famous artists. While Basquiat died of an overdose of just 27 heroin patients, he was linked with the rise of interest in downtown New York artists in the 1980s.

His work addressed his mixed African, Latin and American background through visual language of personal signs, symbols, and figures, and his art evolved quickly from street to gallery in breadth, scope, and ambition. A large part of his work spoke to the difference between rich and poor, and represented his unusual position as a colourful working class person in the world of famous arts. In the years after his death, his attention to (and worth of) his work has been gradually increasing, with the highest price paid for an American artist’s work at the auction in 2017 even established a new record.

The work of Basquiat combined several distinct styles and methods together. He frequently had phrases and texts in his paintings, graffiti, emotive, often abstract, and a profound historical resonance in his logos and iconography. Despite his “unstudied” look, he pulled together a variety of different traditions, practises and styles extremely skilfully and deliberately in order to create his distinctive visual collage.

Many of his paintings depict a tension or an antagonism from two poles – wealthy and poor, black and white, internal and external experiences. This tension and contrast represented his diverse cultural background and his experiences in New York City and in America in general.

Basquiat’s work is an example of how American artists of the 1980s, following the dominance of minimalism and conceptualism on the worldwide art market, begun to reintroduce and emphasise the persona in their work. Basquiat and other Neo-Expressionist artists were seen as a conversation, from the beginning of this century, with the distant Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s and older Expressionism.

The work of Basquiat stands for the acknowledgment of punk, graffiti and counter-cultural practises in the world of art that took place in the early 1980s. In order to comprehend the cultural milieu in which Basquiat has worked, it is necessary to understand the background and the connection between forms, movements and situations in the adjustment of the art world. The critical acceptance and public appreciation of their artists changed sub-cultural settings which were previously seen as opposing to the mainstream art industry.

According to some commentators, Basquiat’s quick rise in popularity and his sad death from drug overdose embody and embody the overt commercial, hyped-up international art scene of the mid-1980’s. For many observers, this time was a cultural phenomena which related adversely to the mainly artificial economy of the century, at the expense of individual artists and the quality of the works created.

Childhood

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in 1960 in Brooklyn. His mother, Matilde Andradas, was likewise born to Puerto Rican parents in Brooklyn. His dad, Gerard Basquiat, was a Port-au-Prince immigrant in Haiti. The young Jean-Michel was proficient in both English and French because of this mixed background. His early studies of French symbolist poetry would eventually impact the works of art he produced as an adult. Basquiat had early childhood artistic ability, learned to paint and sketch with support from his mother and frequently carried materials (such as paper) from the work of his father as an accountant. Together he and his mother visited numerous museum shows in New York, and at the age of six Jean-Michel joined the Brooklyn Museum as a junior member. He was also a good athlete, participating in his school’s track competitions.

After a vehicle was struck during the street at the age of eight, Basquiat had surgery to remove the spleen. This experience prompted him to study Gray’s Anatomy (first published in 1858), his renowned medical and artistic book, which his mother gave him while he was recovering. The sinewy bio-mechanical imagery of this text, together with the comic book art and cartoons the young Basquiat loved, would one day educate him about the lines he had become renowned for.

Basquiat lived alone with his father after divorce with his parents, and his mother was judged not suitable for him because of her mental health issues. Basquiat ultimately ran away from home and was adopted by a family acquaintance, citing physical and emotional abuse. Although he spontaneously attended school in New York and Puerto Rico, where his father had tried to relocate his family in 1974, in September 1978 at the age of 17, he was eventually released from Edward R. Murrow High School in Brooklyn.

Early Life

As stated by Basquiat, “I’ve never gone to art school. I did not take the art classes I took in school. I’ve only looked at a bunch of stuff. And thus, through gazing at it, I learned about art “There was a mistake. Basquiat’s work was based in the graffiti movement in New York in the 1970s. After he joined a theatre company called The Family Life Theater on the Upper West Side, he created the SAMO character, a guy who attempted to sell false religion to audiences. In 1976, he and a buddy of an artist, Al Diaz, began painting spray structures under the name of a pen in lower Manhattan. The SAMO works were mostly based on text and conveyed a message against the establishment, anti-religion and anti-politics. The content of these messages was complemented with logos and imaging, later on in the solo work of Basquiat, especially the three-pointed crown.

The media attention was quickly paid to the SAMO works by the countercultural press, especially the Village Voice magazine that chronicled art, culture and music that distinguished itself from the mainstream. When Basquiat and Diaz agreed that they would cease to work together, Basquiat concluded the project with the following message: SAMO IS DEAD. This statement was published in 1980 on the façade of many SoHo art galleries and downtown buildings. Following the statement, Basquiat’s friend and partner in street art Keith Haring organised a SAMO fake wake in the East Village subway night club Club 57.

In that time Basquiat was often homeless and had to sleep in friendly flats or parking beds and supported himself by hand-painted postcards and t-shirts. However, he was a frequenting centre clubs, especially Mudd Club and Club 57, where he was known as the “baby crowd” of younger people (this group also included actor Vincent Gallo). Both clubs were popular hang-grounds for a new generation of visual artists and musicians, including Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, film directors Jim Jarmusch and Ann Magnusson. Haring was a prominent adversary and friend in particular, and the two frequently recalled as striving to enhance the breadth, size and ambition of their work. At comparable times in their careers, both were recognised and progressed in tandem to reach the heights of the world of art.

Because of his absorption in this downtown stage, Basquiat started gaining more chances to exhibit his work and became a major character in the new creative movement of the city centre. For instance, he featured in Blondie’s video Rapture, as a nightclub DJ and cemented his cache into the “new wave” of hip music, art, and movie from the Lower East. He also established and played with his band Gray around this period. Basquiat was critical of the absence of colourful people in the downtown, but also spent time uptown with graffiti artists in the Bronx and Harlem in the late 1970s.

Following his work on the famous Times Square Show in June 1980, the reputation of Basquiat grew, with his first solo show held in 1982 in the Annina Nosei Gallery in SoHo. Artforum article by Rene Ricard, “The Radiant Child” published in December 1981, reaffirmed Basquiat’s status as a rising star in the broader art world, along with the combination of uptown graffiti and the downtown punk cultures reflected by his work. Basquiat was recognised by the German Neo-Expressionism movement that came to New York and offered a pleasant venue for its own clever, curbside expressionism. Basquiat started to show frequently with artists like as Julian Schnabel, and David Salle, who all reacted to the recent art-historical dominance of conceptualism and minimalism to one degree or another. Neo-Expressionism heralded the resurrection of the painting and its reappearance in contemporary art. Images of the African diaspora and classical Americana marked Basquiat’s work at that time, several of them included in solo exhibitions in the mid 1980s at the renowned Mary Boone Gallery (Basquiat was later represented by art dealer and gallerist Larry Gagosian in Los Angeles).

Mid Life

For Basquiat, 1982 was an important year. He launched six solo exhibitions in towns around the globe and was the youngest artist ever to participate in Documenta, the renowned international exhibition of contemporary art that takes place every 5 years in Kassel, Germany. During this period, Basquiat produced 200 pieces of art and established a trademark motif: a black oracle figure, heroic and crowned. Among Basquiat’s influences for his work in this time were the famous jazz guitarist Dizzy gillespie and boxers Sugar Ray Robinson and Muhammad Ali. Sketchy and sometimes abstract, the portraits caught the spirit of their people rather than the physical resemblance. The fury of Basquiat’s approach was designed to expose what he considered his subjects to be their inner self, their secret emotions and their innermost aspirations with slashes of paint and dynamic line shocks. These works also strengthen their subject’s intelligence and passion, rather from being focused on the fetishized black male body. Another legendary figure, modelled on the West African griot, is also quite significant in this Basquiat period. Griot’s past has spread via history and music to Western African culture and is usually represented by Basquiat with his gloomy and glaring elliptical eyes firmly focused on the viewer. The creative techniques and personal advancement of Basquiat corresponded to a larger Black Renaissance in the art scene of New York of that time (exemplified by the widespread attention being given at the time to the work of artists such as Faith Ringgold and Jacob Lawrence).

By the beginning of the 1980s, Basquiat had become friends with Andy Warhol, who worked with him on a series of works such as Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper) from 1984 to 1986. (1985-86). Warhol typically first painted, and then Basquiat layered his work. In 1985, Basquiat was named the hot young American artist of the 1980s by New York Times Magazine. This connection became the source of contention between Basquiat and many of his colleagues in the centre since it seemed to represent a new interest in the economic aspect of the art industry.

Warhol was also attacked for the possible use of a young, trendy colour artist to bolster his own credentials as related to the increasingly important East Village milieu. Overall, either public or reviewers did not welcome these collaborations and are frequently seen as smaller works by both artists.

Maybe because of his sudden popularity and commercial pressure on his art, Basquiat was more hooked to both heroin and cocaine at this time in his life. Several acquaintances associated this dependence with the stress of continuing their careers and of being a coloured person in a mainly white creative environment. In 1988, at the age of 27, Basquiat died of a heroin overdose in his flat.

Late Life

Nevertheless, Jean-Michel Basquiat played a significant and historic part in the development of the New York Centre’s cultural scene and more generally Neo-Expressionism. While the wider audience was attached to his superficial exoticism and was attracted by his sudden fame, his art, sometimes erroneously defined as “naif” and “ethnically gritty” had significant links with the expressive predecessors, such as Jean Dubuffet and Cy Twombly.

A product of the famous and trade-obsessed society of the 1980s, Basquiat’s work continues to serve as a symbol for many observers of the perils of creative and societal excess. Like the early-influential comic book superheroes, Basquiat has gathered fame and wealth, and then as quickly falls back onto the Earth, the victims of drug addiction and ultimate overdose.

He has received many post-emergence retrospections at Brooklyn Museum (2005) and the Whitney Museum of American Art (1992) and numerous biographies and documentaries, including Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child (2010) and the feature film of Julian Schnabel Basquiat (1996; with former friend David Bowie as Andy Warhol), Basquiat and his counter-cultural legacy. In 2017 another film, Boom for Real: Jean Michel Basquiat’s Late Teenage Years, was released with the same name in London at Barbican Art Gallery. His work continues to inspire modern artists, and his brief life is a continuous subject of concern and curiosity for a biographic legendary art business.

In this specific era of countercultural New York art Basquiat has joined together with his buddy and contemporary Keith Haring. The works of both artists are often shown side by side (most recently in the exposure ‘Keith Haring I Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines’ 2019 in Melbourne, Australia), and numerous commercial licences have been issued in order to reproduce his aesthetic motives. Recently a number of graphic tees from Uniqlo have been added showing the work of the two artists.

Since his death, the increase of Basquiat’s fame has led other artists to create work influenced or even directly related to his work. This comprises painters, graffiti artists and gallery-based installation artists as well as musicians, poets and filmmakers. Visual artists inspired by Basquiat include David Hewitt, Scott Haley, Barb, and Mi Be in North America, as well as European and Asian artists such as David Joly, Mathieu Bernard-Martin, Mikael Teo, and Andrea Chisesi. Musicians like Kojey Radical, Shabaka Hutchings and Lex Amor have hailed his work as shaping themselves. These three musical artists in particular participated along with others on the collaboration Untitled, a collection published by London based record company The Vinyl Factory in 2019 as a homage to Basquiat.

Famous Art by Jean-Michel Basquiat

Untitled (Skull)

1981

An example of Basquiat’s early canvas work, Untitled (Skull) shows a patchwork skull, which nearly seems like a visual counterpart of the Frankenstein Mary Shelley’s monster, a built and sutured amount of incongruous pieces. Suspended on a backdrop which reveals elements of the New York City metro system, the skull is both a modern graffiti riff with the West’s historical history of self-portraiture, and the “signature piece” The expression on the skull-like face is low, with scratchy stitching indicating an unfortunate mix of the components. The colours employed, which mix and revolve, represent bruises or injuries to the face, which are combined with the jagged lines to indicate violence or its effects.

Untitled (History of the Black People)

1983

Basquiat portrays a yellow Egyptian boat led down the Nile River by the deity Osiris, in the middle of this artwork. On the left of the picture, underneath the words “NUBA” are two Nubian masks, and graffiti-esque tags are riddled with the silhouette of a black dog, reads “a dog guarding the pharaoh” Other texts in the picture are the words “Memphis [Thebas] Tennesee” “sickle” (repeated several times in the central panel and referring directly to slave trade), the text ‘Hemlock’ (at the bottom right corner), the words “slave slave slave”) and the words “El gran espectaculo” (on top of the picture) and “mujer” in Spanish (next to a crudely drawn figure with circular breasts).

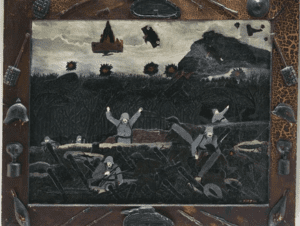

Riding with Death

1988

Death riding is one of Basquiat’s last works and may easily be interpreted as depicting the inner turbulence and growing belief that America’s racist, classist and corrupt character was evident all along, even in the realm of art. The bleakness and truth of the picture and its title, painted in the weeks before his death, is further heightened by the awareness that the artist’s life ends much too quickly after his completion.

Riding with death is less embarrassed and aesthetically complex than many of its previous works and includes a textured brown field, over which Basquiat painted a skeleton-riding African figure. The skeleton rushes on all fours to the left of the picture, while the rider has made his arms less detailed than the bones on which they are sitting. The skull confronts the spectator, his cartoonic dimensions and widespread expression, indicating that gestural graffiti remained a fundamental influence on the work of Basquiat. The simplicity of the backdrop and the topics are evocative of prehistoric cave art and subsequent tribal art in Africa. The African figure’s head is unclear, and its characteristics are darkened by black scribbles aside from one eye on its front.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- In just the brief years of his career, Jean-Michel Basquiat went from a graffiti artist to a downtown punk scenester to a famous art star.

- This vertiginous upsurge led me from sleeping on New York City streets to becoming friendly with Andy Warhol and joining the elite American art scene as one of neo-most Expressionism’s famous artists.

- While Basquiat died of an overdose of just 27 heroin patients, he was linked with the rise of interest in downtown New York artists in the 1980s.His work addressed his mixed African, Latin and American background through visual language of personal signs, symbols, and figures, and his art evolved quickly from street to gallery in breadth, scope, and ambition.

- A large part of his work spoke to the difference between rich and poor, and represented his unusual position as a colourful working class person in the world of famous arts.

- In the years after his death, his attention to (and worth of) his work has been gradually increasing, with the highest price paid for an American artist’s work at the auction in 2017 even established a new record.The work of Basquiat combined several distinct styles and methods together.

- Many of his paintings depict a tension or an antagonism from two poles – wealthy and poor, black and white, internal and external experiences.

- This tension and contrast represented his diverse cultural background and his experiences in New York City and in America in general.Basquiat’s work is an example of how American artists of the 1980s, following the dominance of minimalism and conceptualism on the worldwide art market, begun to reintroduce and emphasise the persona in their work.

- Basquiat and other Neo-Expressionist artists were seen as a conversation, from the beginning of this century, with the distant Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s and older Expressionism.The work of Basquiat stands for the acknowledgment of punk, graffiti and counter-cultural practises in the world of art that took place in the early 1980s.

- In order to comprehend the cultural milieu in which Basquiat has worked, it is necessary to understand the background and the connection between forms, movements and situations in the adjustment of the art world.

- The critical acceptance and public appreciation of their artists changed sub-cultural settings which were previously seen as opposing to the mainstream art industry.According to some commentators, Basquiat’s quick rise in popularity and his sad death from drug overdose embody and embody the overt commercial, hyped-up international art scene of the mid-1980’s.

Responses