Born: 1848

Died: 1894

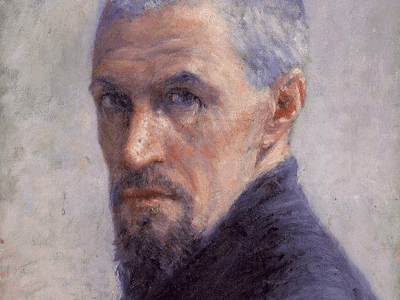

Summary of Gustave Caillebotte

Gustave Caillebotte remained mostly forgotten until the 1950s, despite having accomplished a great deal in Paris during the time of the Impressionists. As with many of his peers in the avant-garde, he was intrigued by the changes that had occurred in Paris as a result of industrialization and modernization. When it comes to masterpieces, most people consider Monet’s and Degas’s early works to be better examples of realism than impressionism because of their resemblance to Millet’s and Courbet’s. There are paintings in his body of work that show off the Impressionist style’s distinctive loose brushwork and lighter palette, but his best known works are large-scale, precise “evocations of photographic naturalism,” as one critic put it, although the comment was meant to be taken disparagingly at the time. In the end, his choice of subject matter was what set him apart from his Impressionist peers the most: he painted subjects from daily life rather than those preferred by academic artists with formal training.

Caillebotte, like a number of the other Impressionist painters—most notably Degas—was a voracious picture collector. Some of the main formal elements borrowed from photography are readily apparent in the work of both artists. There is a severe cropping of an image, similar to how a camera lens removes a part of a scene, that is often used. Several of his compositions seem to have been influenced by photos taken by his brother Martial, a talented photographer who received little acclaim for his work.

Caillebotte, like many of his Impressionist and Post-Impressionist contemporaries, drew inspiration from Japanese art, particularly printing. As they usually depicted images from everyday life, Japanese prints, especially those from the Edo period, served as thematic inspiration for these painters. Caillebotte’s work shows the formal influence of Japanese prints in the work’s often slanted ground and lofty vantage points, both of which are common to Japanese prints.

In the decades that followed his death, Caillebotte gained notoriety for being a significant financial backer and patron of a number of his artistic peers, including close friends Renoir and Monet as well as Manet and Pissarro.

During the decades after his death, Caillebotte gained notoriety as a generous contributor to the French government who left behind a significant collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, as well as a great number of his own works of art. As a matter of fact, the will stipulated that the works go to the Luxembourg Museum first and then the Louvre Museum, which posed a difficulty since his art was still not generally recognised by the mainstream cultural establishment at the time of its donation.

Childhood

Gustave Caillebotte was born on August 19, 1848, in Paris to a well-to-do family. On rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis in Paris, the family resided. His father, Martial Caillebotte, had acquired the family company in military textiles. At the Tribunal de commerce in the Seine department, the older Caillebotte also served as a judge. By the time he married Celeste Daufresne, Gustave’s mother and his third wife, he had already been widowed twice. Gustave was the oldest of three children born to her and Martial, the other two being Rene and Martial.

Yerres, a 12-mile south of Paris estate located on the Yerres River, became the family’s summer retreat starting in 1860. Because his father had bought land and built a big house there, the young Caillebotte started sketching and painting on the Caillebotte family’s beautifully manicured property.

After graduating from law school in 1868, Caillebotte was granted his licence to practise law the following year. He’s bright and driven, and he studied engineering in college. Caillebotte had only been out of school for a short time when, in July 1870, he was conscripted to serve in the Garde Nationale Mobile de la Seine during the Franco-Prussian War.

Early Life

Caillebotte redoubled his efforts to further his creative career after the war. It was in Léon Bonnat’s workshop that he was inspired to begin actively pursuing an artistic career. Émile Zola, Edgar Degas, and Edouard Manet were among Bonnat’s notable students and colleagues at the École des Beaux Arts, where the painter was an important member of the Realist movement. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, John Singer Sargent, Thomas Eakins, Georges Braque, Jean Beraud, and Edvard Munch were a few of Bonnat’s most well-known pupils throughout the years. Caillebotte embraced his new career with gusto, even enrolling at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1873, but he only spent a few weeks there before returning to his family’s house to work in his own studio.In 1874, Caillebotte’s father passed away. Two years later, his brother René passed away, and his mother passed away in 1878, leaving Gustave and Martial as the sole heirs to the family wealth. Around the time of his father’s death, Caillebotte established several important contacts in the art world, including Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and De Nittis, who were not members of the French Academy. In certain instances, he was a close friend and collaborator with some of the most significant avant-garde artists of that time period.

His first public showing was at the Impressionists’ exhibition in 1876, when he was recognised as part of the “Independent,” “Intentionalist,” and “Intransigent” group of artists. There were eight exhibits of Impressionist paintings in all. Caillebotte, Renoir, Monet, and others held small, independent exhibits of their work in line with the avant-garde style of the Impressionists, who rejected academic painting and the formality of the official Salon’s conventional exhibition procedures.

The Floor Scrapers (1875), one of Caillebotte’s best-known works, had been rejected by the judges of the Salon of 1875, the official exhibition sponsored by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. At the third exhibition in 1876, which Caillebotte helped finance and organise, he displayed eight paintings, including this one (French Academy of Fine Arts). As a result of its depiction of ordinary workers planning a wood floor, it was labelled “vulgar.” While the artistic establishment may have accepted Corot’s depictions of bucolic peasants in bucolic settings, realist painters like Courbet, Manet, Degas, and then Caillebotte (among others) produced representations of the working class that were deemed unacceptable and therefore rejected from official recognition.

Beyond being an accomplished artist, Caillebotte was a significant patron and financial supporter of emerging painters like Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro, who were vying for attention and recognition. Affluence from his family allowed him to not only pursue his own creative career but also to assist his less fortunate artist colleagues by providing financial support, as well as to collect their work by paying inflated rates. A number of times, he paid the rent for several of the painters’ studios. In 1876, he made his first purchase of a Monet painting.

Caillebotte was a picky patron when it came to art, supporting just a select few of his favourite painters. For example, he never purchased a painting by Georges Seurat or a drawing by Paul Gauguin; he also didn’t own any works by Symbolist painters. While doing this, Manet helped convince the Louvre Museum to purchase the contentious artwork Olympia by Edouard Manet (1863). When it came to collecting, Caillebotte’s interests went well beyond the fine arts. He also built up a world-class stamp collection, which is currently housed in the British Library in London.

Mid Life

However, Caillebotte’s style did not explore the effects of light by the time of the third Impressionist exhibition in 1877; he had become not only a central organiser of what had evolved into an independent, unofficial, and distinctly experimental salon, but he was also an important force in this new avant-garde movement as well. His paintings were more realist in style, comparable to the early works of Claude Monet and Gustave Courbet as well as Édouard Manet. A number of his paintings were included in future Impressionist exhibits. However, he notably withdrew his piece from the sixth show because of his disagreement with Degas’ inclusion. It was the next year that he took part in the sixth Impressionist show, exhibiting 17 paintings and resolving yet another conflict between Caillebotte and Pisarro, which Monet successfully mediated. However, by the time of the final exhibition in 1886, both Claude Monet and Édouard Caillebotte had declined to take part.

A home and land in Petit-Gennevilliers, a northern suburb of Paris, had been purchased by Caillebotte in 1881. In 1888, he made it his permanent home. His new passion of boat building, which he had previously tried racing, occupied most of his time in 1882, along with other collecting hobbies, including gardening. Martial and Renoir, who visited the home in Petit-Gennevilliers often and liked conversing about philosophical, literary, political, and artistic topics, occupied the bulk of his time. It’s believed that Caillebotte had a long-term romance with a lady named Charlotte Berthier, but they never got married. When he died, Caillebotte left her a sizable pension despite the fact that she was 11 years younger than him and came from what seemed to be a lower-class household.

Late Life

It wasn’t until the early 1890s that Caillebotte was no longer painting on the enormous scale of earlier decades. He died of a stroke in 1894, when he was 45 years old and working in his garden at home in Petit-Gennevilliers. The renowned Pere Lachaise Cemetery in southeast Paris is where he was laid to rest after his death.

After Caillebotte’s death, his heirs tried to make a substantial gift to the French government in accordance with his wishes. After the unexpected death of his brother René in 1876, the artist wrote his last will and testament. He left instructions in his will that read: “I give to the French State the paintings that I have; nevertheless, since I want that this donation be accepted and in such a manner that the paintings go neither in an attic nor in a provincial museum, but… in the Luxembourg Museum and later in the Louvre Museum, it is necessary that a certain time passes before execution of this clause… His brother Martial and the executor of his estate, Renoir, were to wait twenty years before handing over the paintings, as he had instructed them to do.

The gift sparked debate, highlighting the French Academy’s continued hostility toward avant-garde art and artists even as late as 1894. Artist Jean-Leon Gerome led Academy authorities in their effort to keep paintings by Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne from being transferred to the French National Museum. Works that were previously rejected from official Salons because of their so-called “unhealthy” nature by the art establishment are today regarded as some of the most significant examples of the late-19th-century modernist movements in France. Only a small part of the collection’s artworks were approved, including Degas pastels and paintings by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Cézanne, and Millet, as well as only two pieces by Caillebotte himself. One of the most important Modernist collections in the world is the one amassed by the Albert C. Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which was founded in 1911 by a physician, businessman, and collector from the United States of America.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that works by Caillebotte and other artists he’d collected over the years started to be sold from his family’s private collection that they were remembered. It wasn’t until Doctor Barnes, an American businessman and art collector, bought a large majority of the works in 1954 that the Art Institute of Chicago acquired Caillebotte’s painting Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877). This drew the attention of American art collectors and the general public to his work. By the 1970s, there had been a shift in the way people saw his work.

Artists who followed Caillebotte were inspired by his unconventional compositional methods, which angered critics and academics at the time. Paintings by avant-garde painters such as Van Gogh and Picasso used unique viewpoints and cropping that resembled photos, such as looking up from below a slanting floor, peering down from a low perch, or standing on the edge of an intimate setting. In the 1970s, even the photorealists (also known as hyperrealists or superrealists) used photos to create their artwork.

Famous Art by Gustave Caillebotte

The Floor Scrapers

1875

In 1875, Courbet submitted this picture to the French Academy’s official display, but the Salon jury rejected it because they deemed it “vulgar.” They felt that portraying ordinary labourers, such as those repairing wood floors, as heroic was “unheroic,” and the odd, skewed perspective was deemed too radical. In spite of Émile Zola’s defence of the Impressionists, this piece was labelled “anti-artistic” and “photographic” by the avant-garde critic. In his words, “so accurate that made it bourgeois.” the art was. There is little doubt that Caillebotte’s masterpiece The Floor Scrapers captured the attention and admiration of several of the Impressionist artists, who convinced him to show it at their second exhibition in 1876. Floor Scrapers is considered one of his finest works.

Paris Street, Rainy Day

1875

When Caillebotte showed Paris Street, Rainy Day with five other works the year before, Zola, the renowned critic, had a far more favourable opinion of the artist’s work than when he attacked The Floor Scrapers. Finally, Zola wrote: “At last, I will name Mr. Caillebotte, a young painter of the most beautiful courage and who does not give up in front of full-size modern subjects,” a topic that the critic passionately defended. He called the characters in the foreground, a man and a woman, “beautifully truthful” and believed that Caillebotte, once his skill “softened a little,” might be considered “one of the boldest of the group” of Impressionists.

Pont de l’Europe (Europe Bridge)

1876

Caillebotte’s 1876 picture of the Saint-Lazare Train Station shows pedestrians and even a dog crossing or pausing to gaze at the railway lines. Zola praised the piece when he displayed it the same year it was created. Six main avenues were connected by the newly built bridge, each of which was named after a European city. The view is from the street de Vienne, which is where the viewer is located. The artwork prominently displays one of the massive iron trusses of the Pont de l’Europe. This image’s main emphasis is on a couple walking over a bridge. The dog and the two people, who seem to be dating, are going in opposite directions, emphasising the scene’s dynamic nature.

View of Rooftops (Snow Effect)

1879

As Caillebotte’s painting career gathered pace, he contributed more than 25 works to the inauguration of the fourth Impressionist exhibition in 1879, including this and another roofscape. He was one of the most generous supporters of the Impressionists at this time, and no one questioned if he was one of them at the time. His roofscapes, in contrast to some of his more contentious previous exhibits, drew little criticism. It’s essential to note that these paintings aren’t just a throwback to his earlier work, which was influenced by his peers’ interest in seasonal and weather-related impacts on both urban and rural locations.

Nude on a Couch

1880

This painting also features a working-class Parisian. The naked lady lying on the sofa has taken off all of her clothes and thrown them carelessly on the end of the couch over her head, as seen here. Her shoes, along with the condition of her clothing, indicate she is not well-off, as they sit near the sofa. She seems to be asleep since she has one arm over her eyes to block off the light. This isn’t your usual nudity, with a reclining woman in a sensuous position. Normally, a naked woman would be shown with her eyes fixed on the spectator, as if she were making a sexual or sensuous gesture. Although it’s not quite apparent from the photo, this lady seems to have passed out while posing. As a result of the subject not making eye contact with the spectator, the viewer assumes a perspective position similar to that of the artist. It’s also a little claustrophobic in there. Because of the sofa’s odd angle, we get the impression that we’ve come into the room at an inconvenient time. The couch extends beyond the image plane and gives the impression that we’re really in the painting because there’s no barrier between us and it. It’s important to note that the artwork is almost life-size, which adds to the immersive experience.

Man at His Bath

1884

Despite the fact that Man at His Bath was painted in 1884, it was not shown until 1888 at the Les XX exhibition in Brussels, where it elicited a strong reaction from the general public and art critics alike. This artwork, which measures 57 by 45 inches, is almost life-size like many of his others. To pull the spectator into the scenario, Caillebotte has produced a weird and intimate vantage point, as if stooping slightly in the front, so that even the male figure’s genitals, who is towelling himself off after bathing, are visible—and in an unintended manner. Even his wet footprints haven’t dried yet, proving he isn’t posturing but is instead lost in the routine of taking a bath.

Chrysanthemums in the Garden at Petit-Gennevilliers

1893

Caillebotte’s still-life paintings, like those in other genres, reflected his unique style, a mix of realism and unconventionality. With its earthy tones (the spectator may see themselves in the artist’s home garden amid these flowers since they appear so genuine), the composition’s flatness is jarring. It’s as though Caillebotte purposefully omitted any modelling or contrasts of light and dark that could have contributed to the sense of depth. This results in a cascading effect where the flowers, branches, and leaves cover the whole image plane, transforming the canvas into a beautiful panel. Although it’s unlikely, some scholars believe this picture was meant to be used as a door panel, with its lower part attached to it so that a spectator might see it from above and be drawn to the blossoms at its apex.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Gustave Caillebotte remained mostly forgotten until the 1950s, despite having accomplished a great deal in Paris during the time of the Impressionists.

- As with many of his peers in the avant-garde, he was intrigued by the changes that had occurred in Paris as a result of industrialization and modernization.

- When it comes to masterpieces, most people consider Monet’s and Degas’s early works to be better examples of Realism than Impressionism because of their resemblance to Millet and Courbet’s.

- There are paintings in his body of work that show off the Impressionist style’s distinctive loose brushwork and lighter palette, but his best known works are large-scale, precise “evocations of photographic naturalism,” as one critic put it, although the comment was meant to be taken disparagingly at the time.

- In the end, his choice of subject matter was what set him apart from his Impressionist peers the most: he painted subjects from daily life rather than those preferred by academic artists with formal training.Caillebotte, like a number of the other Impressionist painters – most notably Degas – was a voracious picture collector.

- Several of his compositions seem to have been influenced by photos taken by his brother Martial, a talented photographer who received little acclaim for his work.

- Caillebotte, like many of his Impressionist and Post-Impressionist contemporaries, drew inspiration from Japanese art, particularly printing.

- As they usually depicted images from everyday life, Japanese prints, especially those from the Edo period, served as thematic inspiration for these painters.

- Caillebotte’s work shows the formal influence of Japanese prints in the work’s often slanted ground and lofty vantage points, both of which are common to Japanese prints.In the decades that followed his death, Caillebotte gained notoriety for being a significant financial backer and patron of a number of his artistic peers, including close friends Renoir and Monet as well as Manet and Pissarro.During the decades after his death, Caillebotte gained notoriety as a generous contributor to the French government, who left behind a significant collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, as well as a great number of his own works of art.

- As a matter of fact, the will stipulated that the works go to the Luxembourg Museum first, and then the Louvre Museum, which posed a difficulty since his art was still not generally recognised by the mainstream cultural establishment at the time of its donation.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses