(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1267

Died: 1337

Summary of Giotto

Giotto is a pivotal figure in the history of Western art. Many of the issues of the Italian High Renaissance were foreshadowed by his paintings, which ushered in a new period in painting that brought together religious antiquity and the growing idea of Renaissance Humanism.

His impact on European art was so great that many historians believe it was not equaled until Michelangelo took over two centuries later.

One of Giotto’s most notable achievements is his exploration of perspective, which he used to provide fresh perspective to religious tales. With an interest in humanity, his work explored the contradiction between biblical iconography and the daily lives of lay worshipers; he hoped that this would bring people closer to God.

Figures and architectural surroundings were both represented in accordance with the optical rules of proportion and perspective in an emotional quality that had never before been seen in great art.

Giotto, hailed as one of the first great Italian masters, infused mediaeval painting with a fresh sense of humanity and expression. Immediately following his intervention, progressive painters began to consider “flat” Christian paintings as lifeless and devoid of human emotion.

Its compassion was accentuated by Giotto’s “new realism,” which was characterised by a keen eye for small details. Using motions and gestures as well as fine costume and furniture elements, he created three-dimensional people. Despite their devotion to Christ, the protagonists of his stories are all human.

At the time of his death, Giotto was hailed as a national hero. A major part of this is owed to the renowned Italian poet Dante who hailed him as the greatest artist of the 14th century, placing him above even Cimabue (originally Giotto’s master).

Giotto was a well-respected figure in the world of architecture. Florence’s first Gothic (decoration as well as function) Bell Tower, which was named after him – Giotto’s Bell Tower – was built by him as master builder for the Opera del Duomo. There is little doubt that the tower is one of Italy’s most stunning campaniles.

Biography of Giotto

Childhood of Giotto

Only a few facts are known about Giotto di Bondone’s personal life. According to legend, he was born in the Mugello mountains to the north of Florence, where the Medici family was originally from and where they would eventually rise to power in Florence.

The writer and artist Giorgio Vasari, in his important 1550 publication The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, gave Giotto’s birthplace and date as a house in the little village of Vicchio.

It’s possible he was born in 1267, as suggested by other sources, but given the maturity of his earliest works, it’s more likely 1266.

Early Life of Giotto

Legend has it that Lorenzo Ghiberti, one of the Renaissance’s most brilliant sculptors, recounts a tale in his 1452 book Commentaries on the Tuscan Artists of the Trecento. Sheep were being herded in the fields when the young Giotto decided to draw one of them from life.

As soon as the great Renaissance painter Cimabue saw the young Giotto’s sketch, he promptly offered the young man a job as an apprentice.

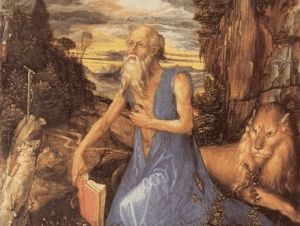

There is some evidence that suggests Giotto was apprenticed to Cimabue when he was as young as 10 years old, where he acquired the craft of painting. While Giotto may have accompanied Cimabue to Rome, the older artist was tasked by the pope to adorn the lower church at Assisi dedicated to St. Francis, which had just been built on top of each other.

His first wife was Ricevuta di Lapo del Pela, better known by her nickname “Ciuta,” and they had several children together. (There’s a myth that Giotto once was asked how he produced such beautiful paintings but such hideous children, and he replied that he formed his offspring in the dark. This is probably untrue.)

Cimabue departed Assisi around the time of his marriage to Ciuta, and Giotto took over his work and was asked to produce a fresco cycle for the upper church’s upper half of the walls.

However, despite Cimabue being Giotto’s instructor, the pupil soon overtook him and was recognised by contemporary poets such as Dante Alighieri in his Divine Comedy: “So what is the point of all this human power?

When it came to painting, Cimabue believed he had the upper hand, but Giotto has since risen to take the glory away from him.”

Mid Life of Giotto

When Giotto initially arrived in Assisi in the years 1290-1295, he began his first major project, during which he made several notable breakthroughs in his technique. Because of his accomplishment, he was given the task of painting a second cycle of frescos for the church.

A trend of regular movement around Italy’s city states began after Giotto’s tenure at Assisi, which would last the rest of his life. It was in these seminars that many of Giotto’s assistants learned the craft and went on to have successful careers of their own.

Giotto visited Florence, Rimini, and possibly Rome around the turn of the century. He spent the next three years in Padua working on one of his most complete and well-known masterpieces, the Arena Chapel, in the city. Giotto may have run into the poet Dante, who had been exiled to Padua from Florence, during his time there.

Giotto appears to have gone frequently between Florence and Rome between the years of 1305 and 1315. He was commissioned by the Roman Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi to make two works: Giotto’s only known mosaic and a massive polyptych altarpiece for St. Peter’s in Rome (the church that predated the modern Basilica) (c.1313).

Avignon, not Rome, served as the papacy’s seat in the early 1300s. Cardinals in Rome fought to have the papacy returned to Rome, and as a result, they commissioned Giotto to create a mosaic for the façade of the ancient St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome’s most important papal basilica, which is now only a smattering of its original glory.

At one point or another, Cardinal Stefaneschi stated his hope that Pope Francis would return and take steps to elevate his seat in Rome’s spiritual hierarchy.

To further his political goals, Stefaneschi may have hired Giotto, who by this point had established a name for himself as an accomplished artist.

Giotto also received important commissions for the church of Santa Croce in Florence during this time period. His work on the chapel for the Peruzzi family, a wealthy and powerful banker family, began about 1313, during which time he painted two fresco cycles showing John the Evangelist and John the Baptist.

“Giovanni” or “John” of the Peruzzi family commissioned the piece, and it appears to have been designed to connect the family, Florence, and the patron saints they prayed to.

Renaissance painters were in awe of the Peruzzi Chapel, which was located in Venice. According to legend, Michelangelo studied Giotto’s frescos, which demonstrated his mastery of chiaroscuro and his ability to precisely depict perspective in antique buildings. It’s well-known that Masaccio drew inspiration from Giotto’s compositions for Cappella Brancacci.

Ognissanti Madonna was also painted by Giotto between 1314 and 1327, according to surviving financial documents. It presently resides in the Uffizi, where it is displayed beside Cimabue and Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna.

However, it is known that Giotto returned to Assisi between the years of 1316 and 1320 to work on the decoration of the lower church (left unfinished by his old master Cimabue). In 1320, Giotto returned to Rome and completed the Stefaneschi Triptych for Cardinal Jacopo, who also commissioned him to decorate St. Peter’s apse (the frescoes were destroyed during the 16th century renovation).

Late Life of Giotto

Robert of Anjou, King of Naples in 1328, summoned Giotto to his court in the city of Florence. Perhaps he was recommended to Robert of Anjou by the Bardi family, who recently completed a sequence of murals for the Bardi chapel in the church of Santa Croce.

To avoid the more perilous wandering existence of his earlier years as an itinerant painter, Giotto settled in Naples as a court painter.

Anjou called him “familiaris” in 1330, a title bestowed upon a member of the royal household after receiving a salary and allowances for supplies and services from the king. Most of his work from this period has perished, a great tragedy for the artist’s community.

Fragments from the Lamentation of Christ in the church of Santa Chiara and the Illustrious Men in the windows of the Santa Barbara Chapel in Castel Nuovo reveal his mark, though historians commonly assign these works to Giotto’s pupils.

The Polyptych for Santa Maria degli Angeli’s church and a possible lost decoration for the Chapel in the Cardinal Legate’s Castle were painted while Giotto was in Naples.

He then briefly returned to Bologna. When Giotto returned to Florence in 1334, it was as if he had never left. While working in Rome, Michelangelo was elevated to the position of ‘capomaestro’, or Master of Municipal Construction Works and leader of Cathedral Masons Guild. Meanwhile, he designed a bell tower for Florence’s cathedral while supervising other artists’ work on its building (though only the lower part was built to his stipulations).

An estimated 200 years passed until the new church was constructed, which was based on the 7th century Santa Reparata church. Construction began in 1301. The church was not finished until 1402. For this reason, Giotto was buried in Santa Reparata, at the city’s cost, following his death on January 8th of that year.

Giotto had a profound impact on the development of the Italian Renaissance and, as a result, on the history of European art. Early Renaissance intellectuals and poets like of Dante and Boccacci recognised Giotto as a master; his explorations of pictorial space and desire for unprecedented realism would go on to influence those in Florence who began the movement toward the Renaissance.

It may be observed in the works of Lorenzo Ghiberti and Donatello in the early 1400s, as well as the young Masaccio’s paintings prior to 1420, where his artistic legacy can be seen in the sculptural revolution.

It is Giotto’s early efforts towards Renaissance Humanism, a school of philosophy that would be critical to the development of Renaissance art, that have had the most impact on his works.

It was a part of the humanist movement to look back to the ancient world for inspiration and knowledge. It is evident in Giotto’s concern in depicting human emotions and in his modelling of the human figure, and in his ability to tear down the distance between biblical characters and human viewers in his artwork.

Giotto’s concern in building, proportion, perspective, and even engineering can be seen as humanistic. Furthermore, they were key parts of later Renaissance humanist thought and art that emphasised depiction of human people, as well as accurate depiction of figures and emotions.

Giotto’s early revolutionary work around 1300 and the big revolution in art that began around a century later were separated by a substantial period of time, and this is worth reflecting on.

Since Giotto’s death occurred during a time of economic collapse and widespread epidemic, this is most likely a result of that period. Pestilence struck Florence and other nearby cities in 1348, wiping out most of Florence’s budding artistic movements and styles.

These cities, including Siena, never recovered from the epidemic’s devastation. Until the early 1400s, Giotto’s work could be appreciated and expanded upon because of the relative stability and wealth of Florence.

Later painters acknowledged Giotto’s impact, and his work enjoyed a rebirth of attention among modernists working in the early half of the twentieth century, including Henry Moore and Roger Fry.

Giotto Facts

What is Giotto famous for?

About seven centuries have passed since Giotto was first acknowledged for his greatness as an Italian painter and the founder of European art as a whole. He is thought to have studied under Florentine painter Cimabue and to have painted frescoes and panel paintings in tempera for chapels at Assisi, Rome, Padua, Florence, and Naples.

What does Giotto mean in Italian?

Giotto is an Italian boy’s name that translates to “pledge of peace.” A well-known Florentine Renaissance artist and architect by the name of Giotto di Bondone, this enticing Italian surname has long been associated with the famous Florentine artist.

What is Giotto most famous work?

Lamentation. Arena Chapel in Padua is home to one of the most famous murals by Giotto, Lamentation of the Death of Christ (a common narrative for 14th century religious art).

What city was Giotto from?

Vicchio, Italy

What did Giotto contribute to the Renaissance?

The Renaissance artists looked to Giotto as a role model for their new style of painting. By introducing the method of drawing precisely from life, he broke with the conventional Byzantine style in a big way.

Did Giotto draw a perfect circle?

The Pope wanted to hire a fresco artist and dispatched a messenger to Giotto, who requested a competitive sample drawing. Giotto used only paper and a pen to draw a flawless circle with a flick of his wrist.

What kind of paint did Giotto use?

A thick layer of egg tempera paint was applied over inky washes. To depict the Virgin Mary’s cloak lining, the artist utilised a mix of yellow iron earth and lead tin yellow.

Who trained Giotto?

It is widely accepted that Cimabue taught Giotto how to paint. Despite the fact that Cimabue was also regarded as a revolutionary painter at the time, Giotto’s fame had surpassed that of Cimabue in Dante’s estimation (read more about Cimabue here).

Famous Art by Giotto

Isaac Blessing Jacob

1290-1295

Giotto’s work in Assisi has long been debated by historians, although there is a general consensus that he painted this and other key frescos. blessing of ibraham As part of a fresco cycle in the Upper Church of St. Francis of Assisi, Giotto’s Jacob is one of the oldest extant paintings.

The murals on the upper half of the church’s walls depict Old Testament stories that were fundamental to the Franciscan monastic order’s teachings. While Isaac’s wife, Rebekah, looks on, we see the elderly Isaac blessing his younger son, Jacob, as he offers food to the boy.

One of Giotto’s earliest attempts to depict believable distance between human figures may be seen in this fresco. However, while Giotto creates an artificial scene by demolishing two of the walls, he also makes it appear like an everyday incident.

We can observe how the foot of the bed recedes, for example, in this painting by Giotto, who used axial perspective, a method in which lines recede parallel to each other and into the distance.

It has been used by painters for millennia, but Giotto’s use of axial perspective blends it with various everyday details to make the interior more accessible.

An opaque curtain separates the room from the rest of the house, and Isaac’s feet are draped over rumpled bed sheets, as though he’d just got out of his nightgown. Isaac, Jacob, and Rebekah, on the other hand, appear to be real people.

Because of how they are draped to imply human structure from shoulders to toes, sheets and clothing also have distinct facial features that add further realism. Isaac’s face is angular and lined around his nose, whilst Jacob’s face has broader cheeks with little hint of bone structure like that of a youth. “

With that said, Jacob’s steady glance at Isaac is a perfect match for Isaac’s pensive, sideways gaze. A new psychological component was added to the proceedings as a result of such humanist improvements.

Later artists, such as Fra Angelico and Masaccio in the early 15th century, were profoundly influenced by Giotto’s more realistic portrayal of human figures and their spatial relationships.

On this occasion, Masaccio repeated Giotto’s perspectival portrayal of architectural features and evoking of emotional response when painting The Expulsion of Adam and Eve in the Brancacci Chapel (c. 1425, S. Maria del Carmine, Florence) (Adam and Eve bend over awkwardly with shame and grief as they walk past an arch receding into the distance).

For Renaissance artists and future generations, Giotto’s fresco reveals significant advancements in European painting techniques.

Crucifix

1288-89

With its 19-foot height and placement on a choir screen, Giotto’s depiction of the Crucifixion sheds light on the artist’s reinterpretation of traditional religious imagery.

Early Byzantine artists depicted the crucifixion with a “Triumphant Christ,” who stands erect and appears to be looking proudly forth from the cross. When Giotto depicts Christ’s agony, he encourages the observer to sympathise with his pain.

Christ’s body appears to hang heavily from the cross in an unusually accurate anatomical representation, just like a real human body would have done. While his stomach is slumped uncomfortably towards the ground, Christ’s muscles look to be strained by their sharp demarcation.

Emotional pain is shown in the scene as his head bows. The Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist stand at the ends of each other’s arms, gazing within at Christ’s agony, and the congregation is asked to join them.

Giotto’s Crucifixion has a more powerful emotional impact when viewed from a lower perspective, as the observer sits or stands beneath the dangling crucifix.

Christ crucified on a cross in a humanistic manner became the dominant form of depiction for following artists. With his Holy Trinity (c. 1425-27), Masaccio parallels Giotto’s depiction of the realistic agony and body weight of Christ in S. Maria Novella in Florence.

At this point, we can clearly see Christ’s body dangling from his muscular arms as a worshipper looks right at us in the painting’s composition.

Celebration of Christmas at Greccio

1300

To show a sacred area that is generally inaccessible to the general public, this work exploits perspective in the Assisi Upper Church. One of Giotto’s fresco cycles, this painting depicts St. Francis crafting the first Nativity scene, now recognised by Christians around the world as a central part of their Christmas celebrations. Giotto vividly depicts St. Francis behind the choir screen, which traditionally divided the church into areas for lay attendees and religious characters, such as the Franciscan monks.

Furthermore, Giotto’s use of perspective to create a distinct space in front of the viewer further accentuates the odd position of the choir screen.

As the floor rises, we can see how the pulpit recedes from us, and we can view the left structure at a raking diagonal from the right. Because the choir screen is open and the crucifix is leaning backwards at an angle, there is extra room there.

Giotto’s fresco, in addition to its aesthetic achievements, provides unique insight into the complexities of social interactions within a mediaeval church, as noted by art historian Jacqueline E. Jung. To the right and left of St. Francis, four Franciscan monks in brown robes are surrounded by well-dressed (and therefore wealthy) individuals.

Lay worshipers are not only allowed behind the choir screen but they can also learn from the monks who stand behind the well-dressed persons with their mouths open, making the scene appear to offer instruction in the holy event before them.

As they stand at the threshold of the choir screen, women are authorised to access this area, but they are positioned in a more ambiguous position: barely on the threshold and prominently in the choir screen.

For art historians and social historians alike, this painting demonstrates a new direction in artistic expression, as well as a different approach to secular and divine belief systems during its creation.

Lamentation

1305

The most famous of Giotto’s frescoes for Padua’s Arena Chapel is his Lamentation of the Death of Christ (a common subject for religious paintings in the 14th century).

Giotto’s frescoes are regarded as one of the greatest examples of pre-renaissance painting, demonstrating a groundbreaking style of naturalism that overturned mediaeval painting standards. The murals in the Arena (or Scrovegni) Chapel represent 39 consecutive scenes from the lives of the Virgin Mary and Christ.

There is a strong sense of redemption running through the story, which may represent the Scrovegni family’s desire to atone for their faults after becoming wealthy through moneylending.

Giotto’s Lamentation depicts a scene in which Christ has been taken down from the cross and his dying corpse is cared for by haloed relatives and followers. Mary Magdalene weeps at Christ’s feet as she cradles her son’s head in her arms.

This gesture of devastation and sympathy for Christ’s suffering by John the Evangelist, on the other hand, shows John’s deep sorrow. They appear to be quivering in anguish as their heads are down in prayer and their mouths are gaping wide as they weep.

Giotto’s mise-en-scène enhances the image’s realism by giving it a stronger sense of place. Deep space is conveyed by the foreshortened figures of the sorrowful angels, as well as the diagonal lines of the mountain ridge.

Byzantine art’s flat, mostly symbolic aesthetic was finally doomed when naturalised human figures and three-dimensional “depth” were combined. The Florentine Renaissance and Renaissance art in general were greatly influenced by Giotto’s approach.

As a result of his belief in the message of St. Francis of Assisi, Giotto’s style conveyed his belief that the mortal could be turned into a better (higher) person by the heavenly touch.

Ognissanti Madonna

1309

Comparing Giotto’s large-scale Madonna and Child with similar works by his slightly older contemporaries Duccio and Cimabue, which hang beside the work in the Uffizi Gallery, reveals the advancements made by the artist. Because of his mastery of architectural perspective, Giotto’s depiction stands out from his peers’ versions of the scene, which were painted 20-30 years after his own.

They are depicted on a throne with steps going up to it, rather than hovering in mid-air, as in prior depictions of the same subject. In this way, the hand raised in blessing by the Christ child serves as the painting’s focal point, bringing all of the painting’s lines of perspective together. In addition, the surrounding figures’ gazes are focused at the holy pair, asking the viewer to do the same and join in the depicted act of veneration.

Furthermore, the painting’s figures are rendered with anatomical accuracy. The human fleshliness of the Virgin Mary and the baby Jesus is explicitly suggested by Giotto, whereas in previous centuries the anatomy of the figures beneath their clothing was rarely given attention. To emphasise this, the fabric of Mary’s garments and the baby’s transparent robe depict Mary’s knees and breasts in a delicate way.

An key impact on Renaissance artists, such as Botticelli’s mentor Filippo Lippi, was the depiction of the Virgin and Child as a human mother and child as well as a divine person. Lippi reduced the gold halos of the Madonna and Child to simple symbolic rings.

Sculptor Henry Moore of the 20th century was also a fan of Giotto’s figurative paintings, praising them as “the finest sculpture I met in Italy.” Giotto’s Madonna and Child is clearly visible in his subsequent mother and child sculptures, which he eventually reworked into his own works.

Design sketch for the Campanile

1334

By the time Giotto’s death came around in 1337, Andrea Pisano and Francesco Talenti had completed the bell tower of Florence Cathedral, which had been started by the artist in 1334. Original design for the bell tower by Giotto is shown in this drawing (campanile).

Architecture has always been a prominent theme in the artwork of Giotto, so perhaps it was only a matter of time until his later career shifted toward architectural design. It was Giotto’s goal to bring out the cathedral’s polychrome, according to Arnolfo di Cambio’s design.

Giotto Tower’s bottom third has been attributed to him, despite the fact that he died before he could be credited with its design. As a result of his work on the cathedral’s design, Giotto joined Brunelleschi and Alberti as one of the Renaissance’s founding fathers of architecture.

Giotto’s sketch depicts a Gothic-style opulent edifice in keeping with his prior paintings’ envisioned structures. A large portion of his body is made up of geometric patterns of colourful marble arranged in a variety of hues. To complete his vision, a group of sculptural reliefs by Giotto, Pisano, and other Florentine artists were created (including Donatello and Luca Della Robbia).

When seen as a whole, the relief cycle depicts civilization’s progression through a succession of panels that celebrate knowledge and thought. Relievos (relievos) communicate the idea of exploration and learning through technology and theology making humanity worthy of divine redemption.

Science and technology are shown through the use of allegory in the form of astronomy, weaving, navigation, and mathematics. Panels depicting biblical and classical figures lie alongside these panels, while the panel symbolising medicine displays the doctor’s consulting chamber as he observes urine enclosed in the glass receptacles (matula) against the light to signify the link between observable analysis and diagnosis (indeed, the matula was taken up as an emblem by practising physicians). Astronomy is the focus of the upper sections of the Bell Tower.

Gionitus, the “creator” of astronomy, uses astronomical equipment to hunt for celestial bodies in the relief on the south side (facing via de’ Calzaiuoli). On the west side, a celebration of mediaeval astronomical figures is depicted on the relief.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Giotto is a pivotal figure in the history of Western art.

- Many of the issues of the Italian High Renaissance were foreshadowed by his paintings, which ushered in a new period in painting that brought together religious antiquity and the growing idea of Renaissance Humanism.

- His impact on European art was so great that many historians believe it was not equaled until Michelangelo took over two centuries later.

- One of Giotto’s most notable achievements is his exploration of perspective, which he used to provide fresh perspective to religious tales.

- With an interest in humanity, his work explored the contradiction between biblical iconography and the daily lives of lay worshipers; he hoped that this would bring people closer to God.

- Figures and architectural surroundings were both represented in accordance with the optical rules of proportion and perspective in an emotional quality that had never before been seen in great art.

- Giotto, hailed as one of the first great Italian masters, infused mediaeval painting with a fresh sense of humanity and expression.

- Immediately following his intervention, progressive painters began to consider “flat” Christian paintings as lifeless and devoid of human emotion.

- Its compassion was accentuated by Giotto’s “new realism,” which was characterised by a keen eye for small details.

- Using motions and gestures as well as fine costume and furniture elements, he created three-dimensional people.

- Despite their devotion to Christ, the protagonists of his stories are all human.

- At the time of his death, Giotto was hailed as a national hero.

- A major part of this is owed to the renowned Italian poet Dante who hailed him as the greatest artist of the 14th century, placing him above even Cimabue (originally Giotto’s master).Giotto was a well-respected figure in the world of architecture.

- Florence’s first Gothic (decoration as well as function) Bell Tower, which was named after him – Giotto’s Bell Tower – was built by him as master builder for the Opera del Duomo.

- There is little doubt that the tower is one of Italy’s most stunning campaniles.

- Biography of Giotto

- Childhood of GiottoOnly a few facts are known about Giotto di Bondone’s personal life.

- According to legend, he was born in the Mugello mountains to the north of Florence, where the Medici family was originally from and where they would eventually rise to power in Florence.

- The writer and artist Giorgio Vasari, in his important 1550 publication The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, gave Giotto’s birthplace and date as a house in the little village of Vicchio.

- It’s possible he was born in 1267, as suggested by other sources, but given the maturity of his earliest works, it’s more likely 1266.Early Life of GiottoLegend has it that Lorenzo Ghiberti, one of the Renaissance’s most brilliant sculptors, recounts a tale in his 1452 book Commentaries on the Tuscan Artists of the Trecento.

- Sheep were being herded in the fields when the young Giotto decided to draw one of them from life.

- As soon as the great Renaissance painter Cimabue saw the young Giotto’s sketch, he promptly offered the young man a job as an apprentice.

- There is some evidence that suggests Giotto was apprenticed to Cimabue when he was as young as 10 years old, where he acquired the craft of painting.

- While Giotto may have accompanied Cimabue to Rome, the older artist was tasked by the pope to adorn the lower church at Assisi dedicated to St. Francis, which had just been built on top of each other.

- His first wife was Ricevuta di Lapo del Pela, better known by her nickname “Ciuta,” and they had several children together. (

- There’s a myth that Giotto once was asked how he produced such beautiful paintings but such hideous children, and he replied that he formed his offspring in the dark.

- This is probably untrue.)

- Cimabue departed Assisi around the time of his marriage to Ciuta, and Giotto took over his work and was asked to produce a fresco cycle for the upper church’s upper half of the walls.

- However, despite Cimabue being Giotto’s instructor, the pupil soon overtook him and was recognised by contemporary poets such as Dante Alighieri in his Divine Comedy: “So what is the point of all this human power?

- Mid Life of GiottoWhen Giotto initially arrived in Assisi in the years 1290-1295, he began his first major project, during which he made several notable breakthroughs in his technique.

- Because of his accomplishment, he was given the task of painting a second cycle of frescos for the church.

- A trend of regular movement around Italy’s city states began after Giotto’s tenure at Assisi, which would last the rest of his life.

- It was in these seminars that many of Giotto’s assistants learned the craft and went on to have successful careers of their own.

- Giotto visited Florence, Rimini, and possibly Rome around the turn of the century.

- He spent the next three years in Padua working on one of his most complete and well-known masterpieces, the Arena Chapel, in the city.

- Giotto may have run into the poet Dante, who had been exiled to Padua from Florence, during his time there.

- Giotto appears to have gone frequently between Florence and Rome between the years of 1305 and 1315.

- He was commissioned by the Roman Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi to make two works: Giotto’s only known mosaic and a massive polyptych altarpiece for St. Peter’s in Rome (the church that predated the modern Basilica) (c.1313).Avignon, not Rome, served as the papacy’s seat in the early 1300s.

- Cardinals in Rome fought to have the papacy returned to Rome, and as a result, they commissioned Giotto to create a mosaic for the façade of the ancient St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome’s most important papal basilica, which is now only a smattering of its original glory.

- At one point or another, Cardinal Stefaneschi stated his hope that Pope Francis would return and take steps to elevate his seat in Rome’s spiritual hierarchy.

- To further his political goals, Stefaneschi may have hired Giotto, who by this point had established a name for himself as an accomplished artist.

- Giotto also received important commissions for the church of Santa Croce in Florence during this time period.

- His work on the chapel for the Peruzzi family, a wealthy and powerful banker family, began about 1313, during which time he painted two fresco cycles showing John the Evangelist and John the Baptist. “

- Renaissance painters were in awe of the Peruzzi Chapel, which was located in Venice.

- According to legend, Michelangelo studied Giotto’s frescos, which demonstrated his mastery of chiaroscuro and his ability to precisely depict perspective in antique buildings.

- It’s well-known that Masaccio drew inspiration from Giotto’s compositions for Cappella Brancacci.

- Ognissanti Madonna was also painted by Giotto between 1314 and 1327, according to surviving financial documents.

- It presently resides in the Uffizi, where it is displayed beside Cimabue and Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna.

- However, it is known that Giotto returned to Assisi between the years of 1316 and 1320 to work on the decoration of the lower church (left unfinished by his old master Cimabue).

- In 1320, Giotto returned to Rome and completed the Stefaneschi Triptych for Cardinal Jacopo, who also commissioned him to decorate St. Peter’s apse (the frescoes were destroyed during the 16th century renovation).Late Life of GiottoRobert of Anjou, King of Naples in 1328, summoned Giotto to his court in the city of Florence.

- Perhaps he was recommended to Robert of Anjou by the Bardi family, who recently completed a sequence of murals for the Bardi chapel in the church of Santa Croce.

- To avoid the more perilous wandering existence of his earlier years as an itinerant painter, Giotto settled in Naples as a court painter.

- Anjou called him “familiaris” in 1330, a title bestowed upon a member of the royal household after receiving a salary and allowances for supplies and services from the king.

- Most of his work from this period has perished, a great tragedy for the artist’s community.

- Fragments from the Lamentation of Christ in the church of Santa Chiara and the Illustrious Men in the windows of the Santa Barbara Chapel in Castel Nuovo reveal his mark, though historians commonly assign these works to Giotto’s pupils..

- The Polyptych for Santa Maria degli Angeli’s church and a possible lost decoration for the Chapel in the Cardinal Legate’s Castle were painted while Giotto was in Naples.

- He then briefly returned to Bologna.

- When Giotto returned to Florence in 1334, it was as if he had never left.

- While working in Rome, Michelangelo was elevated to the position of ‘capomaestro’, or Master of Municipal Construction Works and leader of Cathedral Masons Guild.

- Meanwhile, he designed a bell tower for Florence’s cathedral while supervising other artists’ work on its building (though only the lower part was built to his stipulations).

- An estimated 200 years passed until the new church was constructed, which was based on the 7th century Santa Reparata church.

- Construction began in 1301.

- The church was not finished until 1402.

- For this reason, Giotto was buried in Santa Reparata, at the city’s cost, following his death on January 8th of that year.

- Giotto had a profound impact on the development of the Italian Renaissance and, as a result, on the history of European art.

- Early Renaissance intellectuals and poets like of Dante and Boccacci recognised Giotto as a master; his explorations of pictorial space and desire for unprecedented realism would go on to influence those in Florence who began the movement toward the Renaissance.

- It may be observed in the works of Lorenzo Ghiberti and Donatello in the early 1400s, as well as the young Masaccio’s paintings prior to 1420, where his artistic legacy can be seen in the sculptural revolution.

- It is Giotto’s early efforts towards Renaissance Humanism, a school of philosophy that would be critical to the development of Renaissance art, that have had the most impact on his works.

- It was a part of the humanist movement to look back to the ancient world for inspiration and knowledge.

- It is evident in Giotto’s concern in depicting human emotions and in his modelling of the human figure, and in his ability to tear down the distance between biblical characters and human viewers in his artwork.

- Giotto’s concern in building, proportion, perspective, and even engineering can be seen as humanistic.

- Furthermore, they were key parts of later Renaissance humanist thought and art that emphasised depiction of human people, as well as accurate depiction of figures and emotions.

- Giotto’s early revolutionary work around 1300 and the big revolution in art that began around a century later were separated by a substantial period of time, and this is worth reflecting on.

- Since Giotto’s death occurred during a time of economic collapse and widespread epidemic, this is most likely a result of that period.

- Pestilence struck Florence and other nearby cities in 1348, wiping out most of Florence’s budding artistic movements and styles.

- These cities, including Siena, never recovered from the epidemic’s devastation.

- Until the early 1400s, Giotto’s work could be appreciated and expanded upon because of the relative stability and wealth of Florence.

- Later painters acknowledged Giotto’s impact, and his work enjoyed a rebirth of attention among modernists working in the early half of the twentieth century, including Henry Moore and Roger Fry.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses