(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1909

Died: 1992

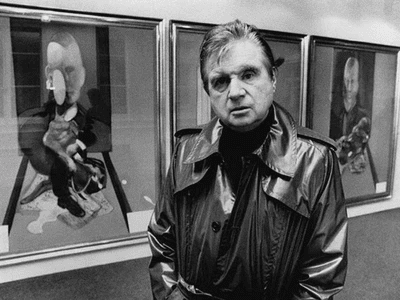

Summary of Francis Bacon

In postwar art, Francis Bacon created some of the most famous pictures of wounded and tortured humanity. He created a particular style that made him one of the most well-recognised exponents of figurative painting in the 1940s and 1950s, drawing influence from Surrealism, cinema, photography, and the Old Masters. Bacon specialised in portraiture, frequently capturing regulars of London’s Soho neighbourhood’s taverns and clubs. His victims were usually depicted as severely deformed souls imprisoned and tormented by existential issues, almost like slabs of raw flesh. One of Britain’s most successful painters of the twentieth century.

Bacon’s paintings elicit strong emotions; entire tableaux, not just the individuals shown on them, appear to scream. Bacon’s unique success in painting was built on his ability to make such forceful messages.

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), the piece that started Bacon’s career when it was shown in London in the closing weeks of World War II, was influenced by surrealism, particularly biomorphism. Many of the issues that would dominate the remainder of his career, such as humanity’s potential for self-destruction and its fate in an age of world conflict, were established in this work.

Bacon’s mature style emerged in the late 1940s, when he developed his previous Surrealism into a technique that drew inspiration from portrayals of motion in cinema and photography, particularly the early photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s studies of people in motion. Bacon not only pioneered new techniques to imply movement in painting, but also helped to bring painting and photography closer together.

Bacon’s success was built on his bold approach to figuration, yet his ideas regarding painting were very conservative. Bacon drew inspiration from the Old Masters, notably Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (c.1650), which he used as the basis for his renowned “screaming popes.” series. Bacon maintained his confidence in the significance of painting at a time when many others had given up on art, stating of his own work that it “deserve either the National Gallery or the dustbin, with nothing in between.”

Childhood

Francis Bacon was born in Dublin and christened after his famous ancestor, the English philosopher and scholar Francis Bacon. During World War I, his father, Edward, participated in the army and afterwards worked for the War Office. Bacon ascribed the violent implications in his works to the tumultuous conditions of his early life in a discussion with critic David Sylvester. Near his boyhood home, a British regiment was stationed, and he recalls hearing troops practising manoeuvres all the time. Because of his father’s job at the War Office, he was exposed to the possibility of violence at a young age. After the war, he returned to Dublin and grew up during the early campaigns of the Irish nationalist movement.

Due to his chronic asthma and the family’s frequent travel for Edward’s job, Francis had little formal schooling. Francis Bacon’s mother, Christina, was a socialite, and with his father gone at business, Francis was frequently left on his own. Bacon had a strong bond with his nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, who eventually came to live with him in London for many years, despite the fact that he had four siblings (the elderly lady may have been very important help to the self-destructive Bacon).

As Bacon battled with his growing homosexuality, his family grew increasingly violent; the young artist was brutally chastised by his father (his father had him whipped by stable lads who had also been part in Bacon’s initial sexual adventures). After his father discovered him trying on his mother’s clothes, he was ultimately kicked out of the family in 1926. Bacon lived as a vagabond, surviving on a little stipend and wandering about London, Berlin, and Paris. Despite his father’s best wishes, the change of environment only allowed Bacon to further explore his sexual identity; his time in Berlin was particularly significant in this respect, and he subsequently described it as a period of emotional awakening.

Early Life

In the late 1920s, Bacon went to London and started interested in interior and furniture design. Bacon was mentored by one of his benefactors, the artist Roy de Maistre, who urged him to take up oil painting. On a vacation to Paris, Bacon was inspired by Picasso and the Surrealists, whose work he had seen. Bacon first showed Crucifixion in 1933, a skeletal black-and-white piece that already exuded the agony and terror that would become characteristic of his later work. Sir Michael Sadler promptly acquired the picture after it was concurrently published in Herbert Read’s book Art Now. Bacon, buoyed by his achievement, decided to stage his own show.

Bacon was unable to join the military during WWII due to his asthma. He was admitted into the Air Raid Precaution sector, which entailed non-military search and rescue, only to be discharged after becoming unwell as a result of the dust and rubble. “If I hadn’t been asthmatic, I might never have gone onto painting at all,” he acknowledged. After the war, he rekindled his interest in painting, with Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944) serving as the actual beginning of his career. The painting’s long necks, cracking jaws, and twisted bodies depict terror and agony, and serve as a powerful reflection on the war’s aftermath. Bacon based the figures on photographs of animals in motion, demonstrating an early interest in the human body’s mobility, which would later become a major topic in his work. The explicit imagery startled reviewers during its display at Lefevre Gallery, yet the numerous critiques thrust Bacon into the forefront.

Mid Life

Following his breakout performance at the 1944 exhibition, he was given further opportunity to work with Lefevre. Bacon was also suggested by Graham Sutherland, a friend and fellow exhibitor, to the director of Hanover Gallery, where he held his first solo show in 1949. For this exhibition, Bacon painted a series called Heads, which was notable for being the first to introduce two important motifs: the scream, which was inspired by a film still from Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin in which an injured schoolteacher is shown screaming (probably in pain); and Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (c.1650), which Bacon only knew a little about.

In 1952, Bacon established one of his most strong connections with Peter Lacy, a former World War II fighter pilot. Lacy was beautiful, well-bred, and self-destructive in equal measure. Lacy once shoved Bacon through a window when inebriated, and the artist sustained a number of (minor) injuries as a result. By 1958, their relationship had deteriorated due to frequent excursions and overseas rendezvous (with both men having a range of sexual partners in between their time together). Sebastian Smee’s book “The Art of Rivalry” discusses a variety of his relationships, particularly his long friendship with Lucian Freud.

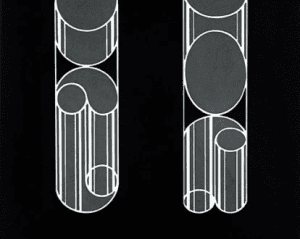

Bacon’s paintings were on display in Hanover in 1953, including Two Figures, a representation of two men embracing in bed that caused a great uproar. Photographs from Eadweard Muybridge, a Victorian photographer, were used to create the piece. “The thing is, unless you look at those Muybridge figures with a magnifying glass, it’s very difficult to see whether they’re wrestling or having sex.” he explained. Bacon preferred to work from images, enlisting the help of his friend John Deakin to shoot his subjects, but he was captivated by Muybridge’s attempts to capture and record bodies in motion.

Bacon was drawn to portraiture because of his proclivity for drawing inspiration from personal experiences. He painted close friends frequently (Lucian Freud, Isabel Rawsthorne, Michel Leiris), and the results have a powerful emotional and psychological impact. Bacon’s companion and lover George Dyer, whom he met in 1964, was one of his most renowned subjects. Throughout their partnership, Bacon painted a number of pictures of Dyer that contrasted powerful muscle with a sense of fragility, such as Portrait of George Dyer Crouching (1966), implying a loving but protective stance toward the younger man.

Late Life

Following the Paris show, Bacon shifted his focus to self-portraiture, stating that “people around me have been dying like flies” and that “there is nothing else to paint but myself.” He continued to work consistently and created a number of paintings in remembrance of Dyer. Many of these were large scale triptychs, such as the well-known “Black triptych” series, which chronicled the circumstances of Dyer’s death. Bacon was the first modern English artist to have a major show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which took place in 1973. Throughout the last years of his life, his work was shown globally, including retrospectives at the Hirshhorn and the Tate Gallery. In the mid-1970s, Bacon met John Edwards, who took over as Bacon’s regular companion and photographer from both Dyer and Deakin. Bacon retreated from his once raucous social life in his latter years, focused instead on his work and his platonic connection with Edwards. At the age of 81, he died of a heart attack in Madrid.

Famous Art by Francis Bacon

Crucifixion

1933

Crucifixion is the piece that first brought Bacon to the attention of the public, long before his postwar achievements. It’s possible that the picture was inspired by Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox (c.1638), as well as Picasso’s Surrealist approach. Perhaps detecting this latter link, Herbert Read depicted Bacon’s Crucifixion next to a Picasso Bather in his book Art Now). Bacon’s concern with pain and terror is introduced in Crucifixion by the transparent whiteness painted over the body frame, which lends a ghostly touch to an already disturbing picture. Crucifixion was shown at a time when the atrocities of the First World War were still fresh in people’s minds. It talked of how violence had transformed the world.

Painting

1946

This mysterious painting’s layered images melt into one another, giving it a dreamy (or nightmare) appearance. The spread wings of a bird skeleton appear to be seated atop a hanging cadaver from the top, the latter image influenced by Rembrandt, as was Bacon’s Crucifixion from 1933. A well-dressed guy with an umbrella sits in a circular cage in the front, which might be embellished with more bones and another cadaver. Bacon’s approach is shown by the odd, collage-like composition of this painting. “The one like a butcher’s shop, it came to me as an accident,” he once commented about the photograph.

Portrait of George Dyer Crouching

1966

When Bacon met the youthful George Dyer, he was in his sixties. Their connection had the feel of a father-son dynamic, despite the fact that it was sexual. Dyer was always in need of comfort and attention, and the bare embryonic figure crouching dangerously on a ledge reflects his weakness. The round sofa, on the other hand, wraps itself about him in a protective hug. The coloration is very pale and muted, yet the red and green accents suggest an inner battle. The painted figure staring downward into a central abyss alludes to Dyer’s longtime addiction to drugs and alcohol.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- In postwar art, Francis Bacon created some of the most famous pictures of wounded and tortured humanity.

- He created a particular style that made him one of the most well-recognised exponents of figurative painting in the 1940s and 1950s, drawing influence from Surrealism, cinema, photography, and the Old Masters.

- Bacon specialised in portraiture, frequently capturing regulars of London’s Soho neighbourhood’s taverns and clubs.

- His victims were usually depicted as severely deformed souls imprisoned and tormented by existential issues, almost like slabs of raw flesh.

- One of Britain’s most successful painters of the twentieth century.

- Bacon’s paintings elicit strong emotions; entire tableaux, not just the individuals shown on them, appear to scream.

- Bacon’s unique success in painting was built on his ability to make such forceful messages.

- Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), the piece that started Bacon’s career when it was shown in London in the closing weeks of World War II, was influenced by surrealism, particularly biomorphism.

- Bacon’s mature style emerged in the late 1940s, when he developed his previous Surrealism into a technique that drew inspiration from portrayals of motion in cinema and photography, particularly the early photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s studies of people in motion.

- Bacon drew inspiration from the Old Masters, notably Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (c.1650), which he used as the basis for his renowned “screaming popes.” series.

Born: 1909

Died: 1992

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Art History, Artists, Resources

Responses