Exploring Picasso’s Spanish Essence

Pablo Picasso stands as a monumental figure in the annals of art, a Spaniard whose brush strokes danced across the canvases of the world with unfettered genius. Born in the sun-drenched city of Málaga, Picasso’s odyssey through the realms of creativity was infused with the rich tapestry of Spanish culture from the outset. This essay weaves a narrative of a young prodigy whose early life and education in Spain’s prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando laid the groundwork for a legacy that would reshape the very fabric of visual expression. As we traverse the poignant episodes of Picasso’s journey, we unearth the profound influences that his heritage imparted upon his oeuvre, from the sorrowful hues of the Blue Period to the avant-garde innovations of Cubism. It is a chronicle that reveals not only an artist but also the heart of Spain itself, beating within every line and colour that flowed from his imagination.

Picasso’s Early Life and Spanish Roots

The Spanish Imprint: Tracing the Lines of Picasso’s Artistic Genesis

The story of Pablo Picasso’s artistic journey is a weave of personal experiences, cultural influences, and historical backdrop that can be traced back to his early life in Spain – a period that laid the foundation for one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

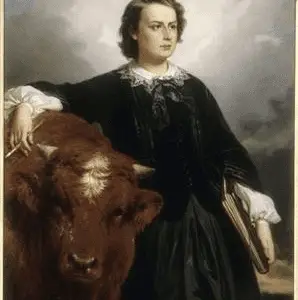

Born in Málaga in 1881, Picasso’s formative years were steeped in the rich tapestry of Spanish culture, with its vibrant colours, intense religiosity, and passionate societal narratives. His father, a painter and art teacher, introduced him to the traditional canon of Spanish art, undoubtedly igniting the first sparks of young Pablo’s creative fervour.

The essence of Spain bled into Picasso’s early works, with a predilection for the dusky palette of earthy tones reflective of Iberian landscapes. One can argue that the olive groves, azure skies and the profound shadows of Spanish architecture punctuated his ‘Blue Period’, where monochromatic shades came to evoke a profound emotional realism.

Yet, it was not merely the visual aesthetics of the Spanish environment that moulded Picasso’s oeuvre. Spain itself was a country rife with political tensions and an undercurrent of social unrest, providing a thematic playground for an artist fascinated by the human condition. The obscure realities of life, from the plight of the poor to the solemnity of sacred traditions, shaped a visual language brimming with empathy and bold statements.

Picasso’s artistic vision was further honed with his introduction to Spain’s luminaries of art. The volumetric treatment of form and the interplay of light and shade, which became a telltale signature of his work, echo the influence of the great 16th-century Spanish artist El Greco. The enigmatic quality of Greco’s elongated figures and mystical aura resurfaces in Picasso’s own forays into pushing the boundaries of reality.

The spectre of bullfighting also wielded a profound impact on Picasso’s work, weaving its way through the visceral depictions of Minotaurs and matadors. This cultural spectacle embodies a dance with death and a dramatic entanglement of brutality and beauty, encapsulating themes that recur throughout Picasso’s extensive canon, particularly in the heralded ‘Guernica’.

As Picasso’s canvas of life stretched beyond his native horizons, the advent of Cubism marked a tectonic shift in the visual arts, yet it never lost the anchoring threads of his Spanish beginnings. The fractured planes and geometric abstraction continued to converse with the soul of Spain, even as the lexicon expanded to engage with international motifs and modernist ideas.

In dissecting how Spain shaped Picasso’s artistic vision, one unwraps a profound narrative where the landscapes of his childhood, the political milieu of his youth, and the cultural bedrock that pervaded his existence coalesced to birth a style unmistakably original, yet undeniably Spanish at its core. Thus, Picasso remains a son of Spain – no matter where his art took shape on the globe, his palette was forever infused with the spirit of his homeland.

Photo by riddle_unsolved on Unsplash

The Blue and Rose Periods

The fascinating journey through Pablo Picasso’s artistic evolution continues as we delve into two of his most poignant and touching epochs: the Blue and Rose Periods. These stages in Picasso’s creative oeuvre epitomise a transformation in both his style and emotional vocabulary, reflecting shades of his inextricable Spanish identity.

Let’s cast a discerning eye on the potent swathes of emotion that coat Picasso’s Blue Period (1901-1904). It was a time marked by profound sorrow following the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas, a tragedy that deeply impacted Picasso. His canvases, awash with myriad blues and greens, evoke a melancholic splendour. The hues serve as a visual elegy, channelling raw sentiments reminiscent of the sombre tones found in traditional Spanish laments and flamenco’s profound ‘cante jondo’. The subjects – the destitute, the forlorn, and the outcast – are painted with an empathy that could be seen to echo Spain’s historic preoccupation with themes of struggle, human suffering, and religion.

The frugal palette transitions during the Rose Period (1904-1906), where warmer pinks, reds, and oranges subtly erupt like a sun-drenched dawn breaking upon Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter. These softer, more optimistic colours signal a shift, reminiscent of the jovial scenes at a Spanish fiesta. Here, itinerant circus performers, jesters, and harlequins take centre stage, their lives wandering and transient much like the gypsies of Spain. It’s within this nuanced tonal shift that the delight in simpler pleasures and the underlying resilience of the Spanish spirit are encapsulated.

Picasso, during these times, never strays far from his cultural heritage. The poised melancholy of the Blue Period and the cautiously optimistic Rose Period perhaps mirror the duality of Spanish identity. Here, one finds a reflection of the sombre religiosity and the effervescent joyfulness that twine through Spain’s cultural fabric.

Be it the haunting solitude of figures like ‘La Vie’ or the lyrical charm of ‘Family of Saltimbanques’, the narrative set within these periods is discrete yet undeniably rooted in the tradition and temperament of Picasso’s homeland. Just as a flamenco dancer commands attention with the emotional intensity of their performance, Picasso’s Blue and Rose paintings capture the viewer with their plaintive beauty and warm allure. These works remain celebrious testaments to the roving heart of the Spanish artist, untethered in his exile but forever bound to the soul of Spain.

Cubism and its Ties to Spanish Culture

Embarking further into the realm of Cubism, one cannot overlook the profound impact of architecture upon this pioneering art movement, and in particular, the structural nuances inherent in Spanish edifices that permeate Picasso’s oeuvre. Cubist works often exhibit a strong sense of geometric rigour, a quality resonant of the Spanish Gothic and Moorish architectural forms that are indigenous to Picasso’s native land. The intricate tesserae of the Alhambra‘s tilework and the perplexing contours of Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia, for instance, echo in the fragmented surfaces and interlocking planes of Picasso’s Cubist compositions.

The fascination with Iberian sculpture, especially ancient Iberian art, also exercised a significant influence on the evolution of Cubism. These archaic forms, replete with a raw and elemental vigour, offered a significant departure point for Picasso’s Cubist exploration. The directness and angularity of these sculptures, mirrored in the prismatic shards and rendered visages of Cubist portraiture, underscore a lineage tracing back to this stark, Iberian aesthetic.

Moreover, one cannot overlook the profound role of Spanish mysticism and symbolism, which imbue Cubism with a layer of profundity surpassing the mere fracturing and rearrangement of form. The esoteric leanings of Spanish culture, with its ancient Judaic and Arabic roots, inject Picasso’s works with an enigmatic quality that invites multiple interpretations and layered readings, akin to a cryptic text waiting to be deciphered. This allure of the unknown and the mystical surfaces subtly in Cubist works, reflecting an intrinsic aspect of the multifaceted Spanish psyche.

Another striking manifestation of Picasso’s Spanish identity within Cubism is the recurrent motif of the guitar, an instrument emblematic of the Iberian soul. Synonymous with flamenco, the guitar not only symbolises Spain’s musical heritage but also serves as a formal device within Cubism to explore spatial relationships and the interplay of voids and solids. The cubist guitars are not merely objects; they are emblems of sound, culture, and innovation, immortalising the Spanish rhythm and reverberating across the expanse of modern art.

Furthermore, the influence of Spanish literary traditions, with their rich tapestry of narratives from Don Quixote to the picaresque novel, can be detected in Cubism’s endeavours to reinvent storytelling through visual fragmentation and perspectives. In a similar stride, Picasso and his contemporaries sought to dismantle the familiar, offering a new lexicon of shapes and a visual syntax novels in their capacity to dissect reality and present it anew.

In essence, Cubism, as pioneered by Picasso, can be contemplated as a canvas where Spanish cultural heritage, its stark dualities and joyous dynamism, merge with the innovative spirit that propelled the modernist narrative forward. Spain’s indomitable stamp on Picasso’s psyche lent Cubism its intensity and depth, far beyond a mere aesthetic—it became a synthesis, a testament to an artist’s lifelong conversation with his roots and their ceaseless capacity to inspire.

Picasso’s Later Works and Spanish Civil War Influence

As the turmoil of the Spanish Civil War enveloped the nation in the late 1930s, its ripples dispersed far and wide, profoundly affecting the lives and work of many, not least the exalted artist Pablo Picasso. The war painted stark lines across the canvas of Spanish society, a dichotomy that would find itself enshrined in the later works of Picasso.

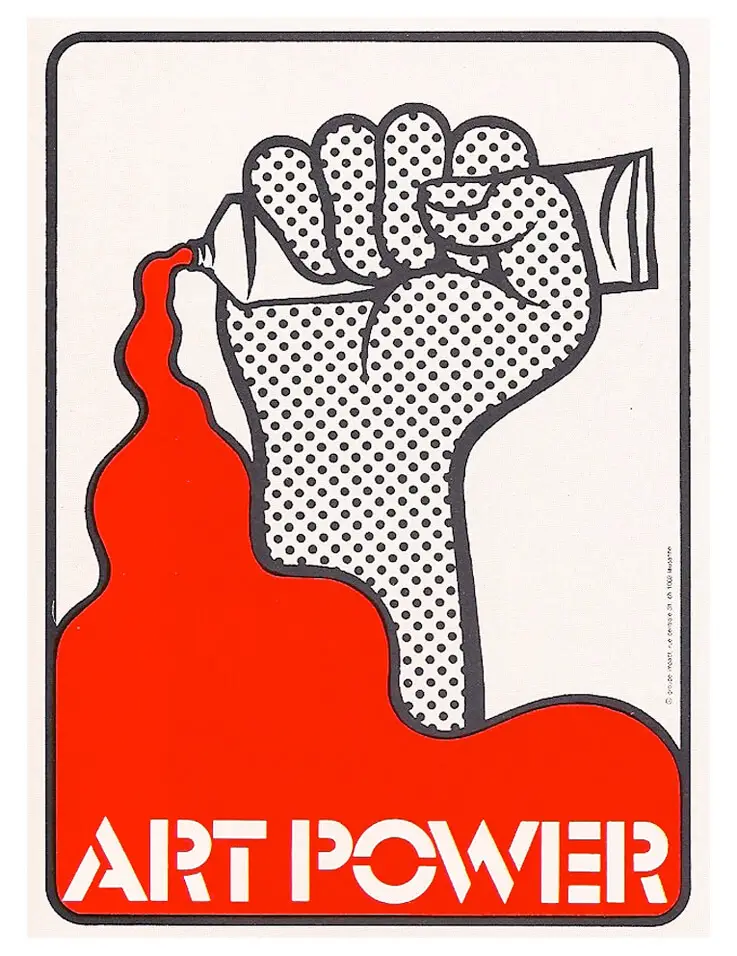

The stark and brutal imagery of the Spanish Civil War was vehemently captured in perhaps one of Picasso’s most famed works: “Guernica.” Crafted in 1937, this colossal mural responded to the devastation wrought by the bombing of the Basque town of the same name. Here, Picasso abandoned the warm hues of his earlier periods in favour of a monochromatic palette, evoking the sombre mood and universal condemnation of warfare’s brutality. “Guernica” was not merely a departure in theme, but a distinct shift that merged the abstract elements of Cubism with a narrative steeped in realism and political engagement.

This engagement with the machinations of war was a thematic compass that directed much of Picasso’s consequent endeavours. The post-war years saw him continually grapple with the anguish and unrest sown by conflict. His art transformed into a kind of pictorial activism, a rebellion on canvas, whose symbols—the weeping woman, the fallen horse, the dismembered warrior—spoke of the relentless suffering that war inflicts.

Moreover, the war’s influence persisted beyond the thematic and percolated into Picasso’s artistic technique. The sharp geometric fragmentation of Cubism, once a vanguard of aesthetic nuance, now became a tool to communicate the fragmentation of society and the human spirit during times of conflict. The Spanish Civil War, thus, marked a period in which Picasso’s art carried a potent political charge, biting in its critique and unflinching in its execution.

In examining the later works of Picasso, it is palpable that the avant-garde legacies of Cubism and Surrealism were infused with an intensified emotional weight and a trenchant social commentary courtesy of the Spanish Civil War. His further works straddled the fine line between evocation and representation, underscoring the deep scars left by the conflict in both the Spanish landscape and the psyche.

This period of Picasso’s oeuvre serves as a vivid testament to the notion that the personal, political, and artistic are a tightly interwoven tapestry. The Spanish Civil War, with its overwhelming grief and strife, unequivocally steered Picasso’s creative trajectory into realms that were hauntingly reflective, uncompromisingly stark, and undeniably poignant—a mirror to the upheaval that had so indelibly marked his homeland. Through his stark, geometric forms, he relayed the shattered peace of a nation in distress, transforming personal anguish into universal artistry—a dialect understood by the eyes of the world.

It can be concluded, without the slightest hint of hyperbole, that the Spanish Civil War instilled in Picasso a profundity that would shadow his artistic journey. It stoked a fire that blazed through his later pieces, combining the memories of despair with a resilient spirit of hope—a fusion that resonates powerfully with viewers, even today.

Photo by cassi_josh on Unsplash

The tapestry of Picasso’s life and art, interwoven with the tumult and beauty of Spain, presents a portrait of an artist inextricably tied to his origins. Through his canvas, we witness the soul of a country; the joy, sadness, and unyielding spirit of a people distilled into images that transcend time and place. As Picasso navigated the shifting terrains of his career, his works remained a steadfast testament to the resilience and complexity of his Spanish identity. Wielding his palette with a fervor that mirrored the revolutionary essence of Spain itself, Picasso’s contributions endure, a mosaic of innovation and passion, reflecting the indomitable character of the land that shaped his earliest dreams and his ultimate masterpieces, such as the indelible ‘Guernica.’ An artist, a Spaniard, and a visionary, Picasso’s narrative is as vibrant and enduring as the culture that forged him, affording us a window into the enduring spirit and heart of Spain.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Art History