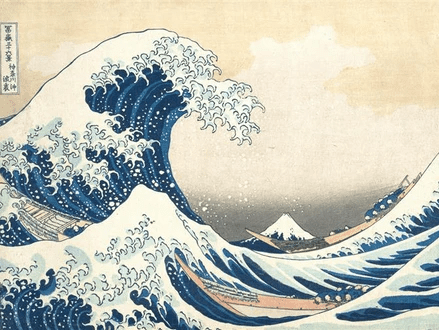

Title of Artwork: “The Great Wave off Kanagawa”

Artwork by Katsushika Hokusai

Year Created 1831

Summary of The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Japanese ukiyo-e artist Hokusai’s woodblock print titled “Under the Wave off Kanagawa,” or simply “Under the Wave Off Kanagawa,” was most likely created in the latter half of 1831 during Japan’s Edo period.

The poster depicts three ships navigating a storm-tossed sea, with Mount Fuji visible in the distance and a massive wave forming a spiral in the centre.

All About The Great Wave off Kanagawa

The first of Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji works, this image introduced Prussian blue to Japanese prints for the first time. As an amalgamation of traditional Japanese prints and Western “perspective,” The Great Wave was an instant hit in Japan and went on to inspire the Impressionists in Europe.

There are several copies of The Great Wave in museums around the world, many of which are from private Japanese print collections built up in the 19th century.

The Great Wave is a yoko-e, or landscape-style print, and it is 25 cm (9.8 in) wide by 37 cm (15 in) high on a ban sheet. A storm-tossed sea, three boats, and a mountain with the artist’s signature in the upper left-hand corner make up the landscape.

The snow-capped peak of Mount Fuji may be seen in the distance. Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji focuses on Fuji, the mountain’s most recognisable feature. As the wave in the foreground, Mount Fuji is shown as a blue dot with white highlights. Three rapid barges known as oshiokuri-bune convey live fish from the Izu and Bs peninsulas to Edo Bay markets.

Kanagawa Prefecture is where the boats are based, with Tokyo to the north, Fuji to the northwest, Sagami Bay to the south, and Edo Bay to the east. Returning from the capital, the boats head southwestward. Each boat has eight oar-wielding crew members.

At the front of each boat, there are two additional relief crew members, totaling 30 men, but only 22 of them can be seen. Oshiokuri-bune were normally between 12 and 15 metres long; if Hokusai’s vertical scale was decreased by 30%, it may be determined that the wave height is approximately ten to twelve metres (as seen in this painting).

As the wave extends out and dominates the landscape before it falls, the composition is based on the shape of a wave. Mount Fuji may be seen in the backdrop as the wave makes a perfect spiral with its core going directly into its centre. Water on the surface is an extension of the curves that are found inside the waves.

Fumes from the huge wave form multiple smaller waves that mimic the pattern of the larger wave. However, the wave’s “claws” of foam have been likened to a “monstrous or ghostly” wave, and it has been likened to a “evil skeleton” frightening the fishermen with its “claws.”

Hokusai’s grasp of Japanese fantasy may be shown in his Hokusai Manga, where he depicted ghosts in wonderful fashion. There are numerous more “claws” lurking below the white foam strip on the left side of the wave. During the 1831-1832 period, Hokusai’s “One Hundred Ghost Stories” series, “Hyaku Monogatari,” dealt more directly with supernatural subjects.

Many of the artist’s earlier works can be seen in this image’s style. As the author frequently describes, even on Fuji, the wave’s silhouette bears a striking resemblance to a dragon.

There are two inscriptions on the Great Wave of Kanagawa. In the upper left corner of the frame, the title of the series, “//,” is inscribed within a rectangular frame. There are 36 different perspectives of Mount Fuji in this poem, which is entitled “Fugaku Sanjrokkei” and translates as “Kanagawa high seas / Under the wave” in English.

The signature of the artist may be seen on the second inscription, which is located to the left of the box. 北斎改为一笔 ‘(Painting) from the brush of Hokusai, who changed his name to Iitsu,” reads the inscription on Hokusai aratame Iitsu hitsu.

Hokusai had no surname, and his initial moniker, Katsushika, was derived from the place where he was born. As he worked throughout his career, he employed more than 30 different aliases, and sometimes left his name to his students.

The Great Wave’s depth and perspective (uki-e) work stands out, with a significant contrast between the foreground and the background. The yin and yang sign is evoked by the contrast between the ferocity of the enormous wave and the calm of the empty background.

Buddhism and Shintoism may be a reference to this scene, in which the boats are washed away by a gigantic wave, which symbolises the fleeting nature of man-made objects (nature is omnipotent). Early morning sunlight is beginning to highlight Fuji’s snowy peak, and the painting appears to be set early in the morning because of the gloomy colour surrounding it. It appears that a storm is brewing, but there is no sign of precipitation on Mount Fuji or in the foreground area.

Many people have tried to imitate The Great Wave, which has become a worldwide icon. Artists and musicians like as Vincent Van Gogh and Claude Debussy were affected by it, as were painters and musicians like Claude Monet and Hiroshige. The printmaking method known as Ukiyo-e was popular in Japan from the 17th through the 19th century.

Japanese woodblock prints and paintings depicting female beauties; sumo wrestlers; kabuki performers; landscapes; flora and fauna; as well as eroticism were produced by its artists. Images of the floating world are known as ukiyo-e (). After Edo (now Tokyo) was chosen as the capital of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603, the ch’nin (merchants, craftsmen, and workers) began to enjoy the city’s burgeoning cultural scene, including kabuki theatre, geisha, and the pleasure districts’ courtesans.

This hedonistic lifestyle was dubbed ukiyo (“floating world”). Affluent members of the chnin class could afford to decorate their residences with ukiyo-e prints or paintings. Hishikawa Moronobu’s paintings and monochromatic prints of lovely women were the first ukiyo-e works to emerge in the 1670s.

It was only in the form of special orders that colour prints were first made available to the general public. Using many woodblocks, painters like Okumura Masanobu were able to print large swaths of colour in the 1740s. Due to the popularity of Suzuki Harunobu’s “brocade prints” in the 1760s, full-color printing became the industry norm.

Each print required ten or more blocks to produce. While some ukiyo-e painters specialised in creating paintings, the vast majority of their works were really prints. For printing, artists rarely carved their own woodblocks for printing; rather, production was divided between the artist, who designed prints, the carver, who cut the woodblocks, the printer, who inked and pressed the woodblocks onto hand-made paper, and the publisher, who financed, promoted, and distributed the works.

It was possible for printers to create effects like colour gradation on the printing block that would have been impossible with machines because printing was done by hand. He was born in 1760 in Katsushika, Japan, a suburb east of Edo, in an area known as Katsushika-ku.

He was born Tokitaro, the son of a shogun mirrormaker, when he was just 14 years old. It’s safe to assume that his mother was a concubine, given that he was never recognised as the heir. He began drawing at the age of six and was hired to work in a bookstore at the age of twelve by his father. As an engraver’s apprentice, he worked for three years at the same time as he was beginning to produce his own artwork.

When he was eighteen, he was accepted as an apprentice by legendary ukiyo-e artist Katsukawa Shunsh. To fill up the void left by Shunsh’s death in 1793, Hokusai began his own independent studies of Japanese and Chinese art, in addition to a few of Dutch and French paintings. In 1800, he published Famous Views of the Eastern Capital and Eight Views of Edo, and he began to accept students.

Hokusai began using the moniker throughout this time era. Over the course of his lifetime, he adopted more than 30 different aliases. As an artist, Hokusai rose to attention in 1804 with the creation of an enormous drawing depicting the Buddhist monk Daruma, which was part of an exhibition in Tokyo. For reasons of survival, he released Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing in 1812 and began to travel to Nagoya and Kyoto in order to attract additional students.

First of fifteen volumes of sketches, known as manga, was released in 1814, which included drawings of people, animals, and the Buddha, as well as other subjects of interest to him. In the late 1820s, he released the well-known series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, which was so successful that he had to produce an additional 10 copies.

In 1849, at the age of 89, Hokusai passed away. Creating this piece was not an easy task for Hokusai. Financial woes plagued him at the age of 60, as did the death of his wife the next year; he was forced to bail out his grandson in 1829 because he couldn’t raise the money himself; and he was left destitute.

The financial consequences persisted for several years despite the fact that he sent his grandson to the countryside with his father in 1830. During this time, he worked on the series of 36 views of Mount Fuji. Possibly because of these flaws, the series was as compelling and inventive as it was.

The Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji appear to be Hokusai’s way of illustrating the difference between the sacred Mount Fuji and the everyday world approximately 1803, refer to the caption Kanagawa-oki Honmoku no zu. for more information on this, see the 1805 painting entitled Oshiokuri Hato Tsusen no Zu. In the second edition of the 100 Views of Mount Fuji, 1834, Kaijo no Fuji is the caption.

Hokusai’s final design for The Great Wave was completed in late 1831, following several years of work and further sketches. Before the release of The Great Wave, there were two similar books, published about 30 years apart. These are Kanagawa-oki Honmoku no Zu and Oshiokuri Hato Tsusen no Zu, two pieces that share the same subject matter as The Tremendous Wave: a sailing boat in the middle of a storm and a rowing boat at the base of a great wave that threatens to overwhelm it.

It is in The Great Wave that Hokusai’s talent as a painter is best displayed. Although the print appears simple to the naked eye, it was the outcome of a protracted and deliberate process of contemplation. When Hokusai published Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing in 1812, it became clear that this method could be used to any object because of the circle-square relationship.

A few years later, for the second volume of One Hundred Views of Fuji, Hokusai returned to the picture of The Great Wave. With the same burst of foam, this print depicts a similar interplay between wave and mountain. Neither people nor boats can be seen in the second shot when wave fragments match with the path taken by a flock of birds in flight.

While the wave and birds in Kaijo no Fuji move in synchrony in The Great Wave, the wave and birds in Kaijo no Fuji move in the other way – from right to left. Right-to-left translation of The Great Tsunami in Japanese emphasises danger of the enormous wave.

It’s common practise for Japanese paintings to be read from right to left, as Japanese text is also read that way. A closer look at the boats in the photograph indicates that the “Japanese” interpretation is valid since the slim, tapering bow points to the left. One more print by Hokusai, Sushichishi from the “Oceans of Wisdom” series by Hokusai, shows a boat sailing against the current, this time to the right, as evidenced by the water’s wake.

In the 18th century, the idea of perspective prints made its way to Japan. Instead of the typical foreground, middle ground, and background, which Hokusai continually rejected, these prints used a single-point perspective. As in ancient Egypt, the scale of objects or persons was determined by the significance of the topic within the setting of a painting in traditional Japanese and Far Eastern art.

Western (especially Dutch) merchants arriving in Nagasaki taught perspective to Japanese artists, which was initially employed by Paolo Uccello and Piero della Francesca in Western paintings. As early as 1750, Okumura Masanobu and Utagawa Toyoharu attempted to mimic the usage of Western perspective by producing engravings representing Venice’s canals or the ruins of ancient Rome in perspective.

As a direct pupil of Toyoharu, Hiroshige and Hokusai impacted Japanese landscape painting through the works of Toyoharu. Shiba Kkan’s investigations in the 1790s introduced Hokusai to the Western perspective, from which he benefitted. The Mirror of Dutch Pictures — Eight Views of Edo was a series he produced between 1805 and 1810.

The triumph of The Great Wave in the West would not have been possible if viewers were unfamiliar with the work. A Japanese perspective on a Western drama is evident in several ways. It was during Hokusai’s “blue revolution” in the 1830s that he began using the popular colour “Prussian blue” extensively in his prints.

While the delicate and swiftly fading indigo colour was usually utilised for ukiyo-e paintings at the period, he used this shade of blue instead. When Hiroshige and Hokusai first arrived in Japan in 1829, they utilised a lot of berorin ai, or Prussian blue, which was imported from Holland in 1820

. Prussian blue was probably suggested to the publisher in 1830 and initially appears in the first 10 prints in this series, including The Great Wave. This new idea was a huge hit from the get-go.

Nishimuraya Yohachi (Eijudo) was Hokusai’s publisher at that time, and he advertised the new technique everywhere in 1831. The following year, Nishimuraya published the next ten prints in the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji series, all unique in that some of them are printed using the aizuri-e technique: images printed entirely in blue.

Ksh Kajikazawa, “Kajikazawa in Kai Province,” is an example of an aizuri-e print of this type. Sumi black with India ink is used instead of Prussian blue to create the outlines on these 10 more prints. The ten prints collectively referred to as “ura Fuji” mean “Fuji from behind.” The initial printing of The Great Wave resulted in some wear on subsequent print editions.

However, the total number of copies printed is thought to be around 8,000. The sky’s pink and yellow hues were the first to show symptoms of ageing, as they fade faster in older versions, resulting in fewer clouds and a more uniform sky, as well as smudged lines surrounding the title box.

As Edo period woodblock prints used light-sensitive colourants, some of the surviving copies have also been damaged. About 100 copies of The Great Wave are still known to exist.

In addition to the Tokyo National Museum and Japan Ukiyo-e Museum in Matsumoto, there are also copies of this print at the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Giverny Museum of Impressionisms in France, the Musée Guimet, and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. The Great Wave can also be found in private collections, such as Gale’s.

For example, the Metropolitan Institution’s copy originates from Henry Osborne Havemeyer’s previous collection, which his widow presented to the museum in 1929. Private collectors of Japanese prints in the nineteenth century were a common source for museum collections of the art. In the same way, the copy in the Bibliothèque nationale de France was acquired by Samuel Bing in 1888 and made its way to Paris.

The Musée Guimet has a copy thanks to a 1932 gift from Raymond Koechlin. Following Japan’s Meiji Restoration in 1868, the country opened its doors to Western goods for the first time in more than a century. As a result, Japanese art swiftly became popular in Europe and the United States. Japonism is a term used to describe the Western cultural impact on Japanese art.

The Impressionists, in particular, found inspiration in Japanese woodblock prints. The Great Wave off Kanagawa, widely regarded as the most renowned Japanese print, had a profound impact on a number of other works of art, including paintings by Claude Monet, music by Claude Debussy, and writings by Rainer Maria Rilke, including Der Berg. One of his favourite works, The Great Wave, was found in Claude Debussy’s studio. With this in mind, he requested that the image of La Mer be placed on its original 1905 score cover.

In the early 1900s, a draughtsman, engraver, and watercolourist named Henri Riviére was impressed by Hokusai’s work, particularly The Great Wave. He was also a driving factor behind Le Chat Noir. In 1902, he created a series of lithographs called The Thirty-Six Views of the Eiffel Tower as a tribute to Hokusai’s work. Japanese print collector Siegfried Bing,

Tadamasa Hayashi and Florine Langweil were among the artists he bought works of art from. As a huge admirer of Hokusai, Vincent van Gogh remarked that The Great Wave had a horrifying emotional impact because of the brilliance of drawing and use of line. The boats in Hokusai’s The Great Wave are replaced by three women dancing in a circle in Camille Claudel’s La Vague (1897).

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Art History, Artworks, Resources

Responses