All About Surrealism

Surrealism Simplified

Surrealism was an art movement that emerged in Europe following the First World War, inspired mainly by Dada. The movement is most recognised for its visual works, texts and the juxtaposition of distant facts in order to awaken the unconscious mind via images.

Summary of Surrealism

The Surrealists tried to canalise the unconscious as a way of releasing the power of imagination. The Surrealists thought rationality and literary realism, and strongly influenced by psychoanalysis, suppressed and weighed down the force of imagination through tabuism. Even under the influence of Karl Marx, they believed that the psyche had the capacity to expose the contradictions and inspire revolution in daily life. Their focus on the power of human imagination places them in the Romance tradition, but they thought that insights may be discovered on the streets and in their daily lives, unlike their forefathers. The Surrealist desire to touch the unconscious psyche and its interests in myth and primitivism influenced many of the subsequent groups.

André Breton described Surrealism as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought.” Breton argues that through accessing their unconscious mind, artists circumvent reason and logic. In practise, such methods became known as automatism or automatic writing, allowing artists to forget conscious thinking and to take chance in the creation of art.

Sigmund Freud’s work had a strong influence on Surrealists, especially his book The Interpretation of Dreams (1899). Freud legitimised the significance of dreams and the unconscious as legitimate disclosures of human feeling and wishes. He gave a theoretical foundation for much of surrealism, exposing the complicated and oppressed internal worlds of sexuality, wants and violence.

Surrealist imagery is arguably the movement’s most recognised aspect, yet it’s also the most difficult to classify and describe. Each artist depended on his own recurrent themes that came from his/her dreams or unconscious thoughts. Basically, the picture is outrageous, confusing and even eerie since it aims to stir the spectator off their comfortable preconceptions. But nature is the most common motif. Max Ernst was fascinated with birds, he had a bird alter ego, and Salvador Dalí’s works are frequently ants and eggs, and Joan Miró was heavily based on hazy biomorphic imagery.

Why is it Called Surrealism

The phrase for Manifeste du surréalisme was used by André Breton, who subsequently established the Surrealist movement (1924), and his description is translated as “pure psychic automatics which are meant to express…….the actual process of thinking.

Everything About Surrealism

The Beginnings

Surrealism sprang from the Dada movement, also revolt against indulgence in the middle class. However, artistic inspirations come from many sources. For many Surrealists, Giorgio de Chirico was the most direct influence. He, like them, utilised strange imagination and troubling juxtapositions (and his Metaphysical Painting movement). Artists from the late past, including Gustave Moreau, Arnold Bocklin, Odilon Redon and Henri Rousseau, were also attracted to these who were interested in primitivism, native or strange images. Even Renaissance painters such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo and Hieronymous Bosch inspired these artists, since they didn’t excessively deal with the aesthetic problems of line and colour, but felt obliged to produce what surrealists considered the “real.”

The Surrealist movement started as a literary group closely related to Dada, which emerged in Paris as a result of the breakdown of Dada when the determination of André Breton to help Dada confronted the anti-authoritarianism of Tristan Tzara. Breton, who is often characterised as “The Surrealist Manifesto.” formally established the movement in 1924. However, in the programme notes for the ballet parade, Pablo Picasso, Leonide Massine, Jean Cocoteau and Erik Satie, Guillaume Apollinaire originally created the word “surrealism,” in 1917.

The group started producing the newspaper La Révolution surréaliste, which focuses mostly on literature but also includes reproductions of painters such de Chirico, Ernst, André Masson and Man Ray, around the time Breton published his first manifestation. It was published till 1929.

The Surrealistic Research Office or the Central Surrealistic Office was also founded in Paris in 1924. This was an informal group of authors and artists who met and held interviews “gather all the information possible related to forms that might express the unconscious activity of the mind.” The office, led by Mr Breton, has established a dual archive: a collection of dream images and a collection of social life-related data. Every day at least two individuals staffed the office – one to welcome guests, the other to jot down the remarks and observations of the visitors who subsequently joined the archive. The Bureau announced publicly its revolutionary purpose in January 1925, which was signed by 27 individuals, including Breton, Ernst and Masson.

Concepts in Surrealism

Surrealism shared much of Dada’s anti-rationalism, whose movement it evolved from. The early Parisian surrealists utilised art as a relief from violent political circumstances and to deal with the uncomfortably felt worldwide. By using fantasy and dream images, artists create creative works via various mediums, exposing their inner thoughts in an excentric, symbolic manner, disclosing concerns and analysing them through visual methods.

Two genres or techniques differentiated Surrealist painting. Artists like Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy and René Magritte painted their dreamlike quality with a hyper-real manner where things were portrayed in sharp clarity and with the appearance of three-dimensionality. The colour of the art was frequently rich (Dalí) or monochrome (Tanguy), both of which suggest a dream state.

Several Surrealists were also very supportive of automatism or automatic writing to delve into the unconscious mind. Artists such as Joan Miró and Max Ernst utilised several methods, including collage, doodling, frottage, decalcomania and scratches. Artists like Hans Arp also produced collages as independent pieces.

Hyperrealism and automatism did not exclude each other. In one piece, for example, Miro frequently utilised both techniques. In each instance, though, it was always strange – intended to shock and confuse the topic or portrayed.

Breton believed that the object had been in crisis since the beginning of the nineteenth century and that this stalemate might be conquered if, for the first time, it was viewed as odd. The approach was not for the purpose of frightening the middle class with la Dada, to create bizarre things, but for what he described as depayment or estrangement. The aim was to relocate the item and “defamilarizing” it from its anticipated setting. Once the item has been removed from its usual settings, its cultural background may be viewed without the mask. These uncongruous pairings of items were also intended to highlight the tense, under the surface of reality, sexual and psychological forces.

A small handful of Surrealists are renowned for their 3D work. Arp was renowned for its biomorphic creations, which started as part of the Dada movement. Pieces of Oppenheim were strange combinations which removed familiar items from their daily environment, whereas Giacometti’s were more conventional sculptural shapes, many of which were hybrid human-insect creatures. Dalí, not so well recognised for his 3D work, produced several fascinating installations, like Rainy Taxi (1938), a vehicle with models and a number of rain pipes in the inside of the car.

Photography played a key part in surrealism because to the ease with which artists produced eerie images. Artists like Man Ray and Maurice Tabard explored automated writing by means of methods such as double exposure, combination printing, mounting and solarization, which completely avoided the camera. For strange pictures, some photographers utilised rotation or distortion.

The Surrealists admired even the prosaic picture separated from its worldly setting and viewed through the surrealist sensitivity lens. In Surrealist journaux, such as La Révolution surréaliste and Minotaure, all of the snapshots, police photos, film stills and documentary pictures were published completely apart from their original objectives. For example, the Surrealists were excited by the photos of Eugène Atget in Paris. In 1926, Atget’s imagery of a Paris which rapidly vanished was published in the Surrealist Revolution at the behest of his neighbour, Man Ray, as spontaneous visions. The surrealist has remembered his own image of Paris as “dream capital.” via Atget’s pictures of deserted streets and store windows.

Although surrealism began in France, it may be recognised in art worldwide. Many artists were pulled into their circle in the 1930s and 1940s, especially as growing political upheavals, and the second world war fostered the idea that human culture was in a state of crisis and collapse. Many Surrealists’ relocation to America during WWII further disseminated their views. But after the war, the group’s beliefs were called into question by the development of existentialism, which was more logical than surrealism, while praising individuality. In the arts, the Abstract Expressionists integrated surrealist concepts and seized their supremacy through new methods that depict the unconscious. As a major aim of the movement, Breton grew more engaged in revolutionary political action. As a consequence, the original movement was dispersed into smaller groups of artists. The Bretons, like Roberto Matta, considered art to be intrinsically political. Others in America stayed apart from Breton like Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. Salvador Dalí, too, fled to Spain, believing in art’s essential position.

The End of Surrealism

In 1936 the New York Museum of Modern Art had an exhibition named Fantasic Art, Dada, Surrealism, which inspired a lot of American painters. Some, like Jackson Pollock, started experimenting with automatic and unconscious images – explorations which would eventually lead to his “drip” paintings. Similarly, Robert Motherwell is considered to be “stuck between the two worlds” of abstraction and automatism.

New York became, in large part due of political upheavals in Europe, not Paris, the emerging hub of a new avant-garde, which emphasised the unconscious with abstraction rather than the “hand-painted dreams” of Salvador Dalí. Peggy Guggenheim’s 1942 Surrealist-influenced artist show, along with European painters Miró, Klee and Masson (Rothko, Gottliebe, Motherwell, Baziotes, Hoffman, Still and Pollock), highlights the rapidity with which Surrealist ideas disseminated to the art world of New York.

The Surrealists were frequently portrayed as a close group of males, and often their work saw women as wild “others” to the cultural, logical world. Work by feminist art historians has subsequently remedied this perception and not only emphasised the number of women Surrealists engaged in the group, in especially in the 1930s, but also analysed the gender stereotypes working in many surrealist works. A number of publications and exhibits have been dedicated to the topic by feminist art critics such as Dawn Ades, Mary Ann Caws, and Whitney Chadwick.

While most of males, particularly Man Ray, Magritte, and Dalí, repeatedly focused and/or distorted the female shape and portrayed females as muses, much like male artists for centuries, female surrealists, like Claude Cahun, Lee Miller, Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning, tried to address the problem of Freudian psychoanalysis. Many Surrealist women thus experimented with dressage and portrayed themselves as animals or as mythical creatures.

Interestingly, many prominent surreal women were British. Elijah Agar, Ithell Colquhoun, Edith Rimmington, and Emmy Bridgwater are some of these examples. A continuous study of human connections with their natural surroundings and most notably with the sea has been particularly important in British interpretation of Surrealist philosophy. Paul Nash acquired a fascination in the things found beside Agar, typically as objects gathered from the shore. The emphasis on the boundary of the land and the anthropomorphic similarity of rocks to the water hit a chord with the British identities and, more broadly, with surrealist ideals of reconciliation and unity.

A major trigger for many British painters was the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936. The movement was led by Roland Penrose and Herbert Read. In Britain, the worldwide icons of Leonora Carrington and Lee Miller were created, as well as another large group of artists around Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. Overall, from the start, there was the privilege of an ex-centered imagination and the fundamental rejection of standardised and logical ways of doing things. This Golden Period for art in the UK in general and in particular British surrealism’s legacy are still influencing art practise in the nation.

Key Art in Surrealism

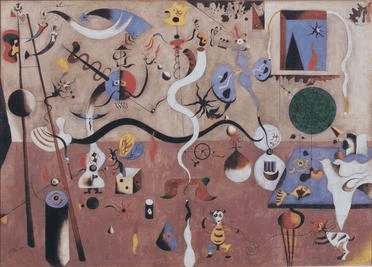

Carnival of Harlequin

By Joan Miró

1924-25

In his work, Miró developed sophisticated and fascinating environments that are an outstanding illustration of surrealism by relying on dreamlike images and using biomorphism. Biomorphic forms are those that resemble biological creatures but are difficult to identify as anything; the forms on the canvas seem self-generating, morphic and dancing. While in Carnaval d’Arlequin a faithful three-dimensional space is suggested, the whimsical forms are all-over quality that Miró had done throughout his Surrealist era and would ultimately lead him to further abstraction. Miró was notably renowned for his use of automatic write methods in the making of his work, especially for doodling or automatic drawing. He is most renowned for his work such as this, depicting chaotic, but cheerful interiors from the Dutch interiors of the 17th century.

The Human Condition

By René Magritte

1933

René Magritte’s famous and enigmatic paintings tend to be cerebral, frequently dealing with visual phrases and the relationship between something represented and the thing itself. In The Human Condition, a linen rests on a stable in front of a curtailed window and reproduces precisely the view outside the window behind the lens, and the image on the stable in one way becomes a scenario, not just a landscape replica. There is no difference between the two, since both are the artist’s fabrications. The hyperrealistic painting technique that surrealists often employ makes the strange arrangement seem dreamy.

Mama, Papa is Wounded!

By Yves Tanguy

1927

Tanguy decided to be a painter at the most critical stage in 1923 when he saw Giorgio de Chirico’s painting in a store display. Next year, Tanguy, the poet Jacques Prévert and the actor and playwright Marcel Duhamel moved to a home for surrealists, a movement he got interested in when he read the journal La Révolution surréaliste. In 1925, André Breton greeted him in the group. Tanguy was inspired by Jean Arp, Ernst and Miró’s biomorphic formes, creating his own ambe-like language that populates dry, enigmatic landscapes, undoubtedly influenced by his adolescent journeys to Argentina, Brazil and Tunisia. In 1927 Tanguy’s mature style was developed despite his lack of formal training, and it was marked by desolate landscapes strewn with strange stones painted with perfect illusionism. The paintings typically feature a cloudy sky with an unending vista.

Birthday

By Dorothea Tanning

1942

Birthday is a self-portrait painted by Dorothea Tanning on her 30th birthday. Looking above, you see the vast spaces recessing into the backdrop that symbolise the unconscious mind of Tanning. A lot of Surrealists thought architectural images fit to convey ideas of a labyrinthine self that evolves and grows through time; one of the greatest instances is birthday. The gargoyle at the feet of the figure is also remarkable. Tanning claimed it was her interpretation of a lemur that was connected with the spirits of death. Tanning combined natural images with items of high culture, such as fantastic clothing and interior design, as a skirt formed of roots, pay tribute to culture, as well as the wilderness and nature as a female creation.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Art Movements, Resources