(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1819

Died: 1900

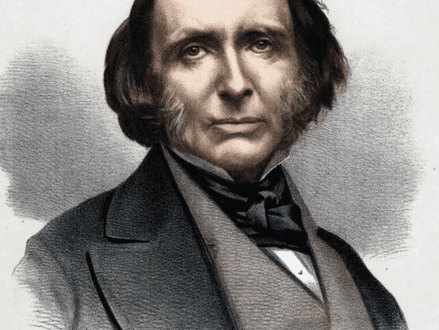

Summary of John Ruskin

Ruskin was a complicated, passionate, and highly eloquent guy who influenced individuals like Mahatma Ghandi, Leo Tolstoy, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. As an art critic and patron, he was also a brilliant watercolourist, a dynamic teacher, a well-respected geologist, and a passionate advocate for social and political reform. He was a real polymath. These driving forces – nature, God, and society – appear often in his writings, and they shaped his forward-looking views. He fought for new painting techniques, historic building preservation, natural landscape conservation, women’s education, and better working conditions for the poor. He also foresaw dangers connected with the Industrial Revolution, such as pollution, decades before the general public did. His thoughts and writing helped young artists gain recognition, aided in the creation of the National Trust, and safeguarded Venice’s historic architecture. His ideas influenced welfare changes in the United Kingdom, such as the minimum wage, free school lunches, and universal health care. among others.

More than 50 volumes, covering everything from art criticism to fiction, political treaties, to travel guides, were published by Ruskin, who was a prolific writer. In these works (which included lecture notes and letters as well as more traditional essays), he shared his revolutionary ideas, and over the course of his career, he streamlines his writing style to make it as accessible as possible to the widest possible range of readers.

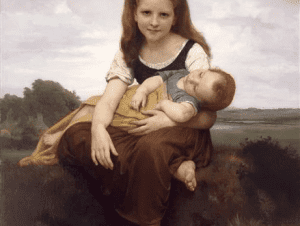

He was a staunch supporter of “truth to nature” as an aesthetic principle encouraging artists to pay careful attention to the landscape and, as a result, to accurately depict nature without romanticising what they observed. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of youthful painters who rejected current ideas of aesthetic beauty in favour of a pre-Renaissance style of painting, benefited greatly from this concept. Due to his focus on nature (as well as his distaste for mass manufacturing), John Ruskin had a significant influence on the growth of the Crafts, Movement.

To many, Ruskin’s work on Neoclassicm encouraged the restoration of the older Gothic style, which he championed with fervour. As a result of his influence on many other architects such as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright as well as Walter Gropius, it’s said that he helped to launch the Garden City Movement.

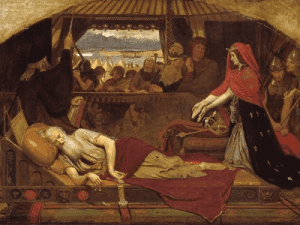

In Ruskin’s min, nature and beauty were intimately linked to notions of the divine, because of his upbringing as a Christian, His conclusion was that portraying religion was best done via realistic depictions of nature and the human body, rather than grandiose religious events. The Pre-Raphaelites took this to heart, and their art sought to harmoniously integrate religious devotion. Instead of idealising religious figures, they portrayed them as members of the working class with filthy clothing and fingernails, which earned them scorn.

Childhood

John Ruskin was born in 1819 in south London, the only child of wealthy wine merchant John James Ruskin and his bar owner wife Margaret Ruskin. His childhood was shaped by summer trips to Scotland and a relocation to Herne Hill in south London’s countryside at the age of four. These early encounters sparked a lifelong passion for the outdoor in him. He receives his education at him, where his father’s watercolour collection and his mother’s devout Protestantism shaped him. His early work in criticism was built on a firm foundation of bible reading and interpretation that Ruskin kept up with on a daily basis. He started writing novels at the age of seven, and his father, who hoped his son would be successful, paid him for his poetry.

Early Life

Family fortune enabled for several trips across the UK and Europe, with stops in places like Italy, France, and Belgium among others. Especially inspires by the Lake District’s natural beauty, Ruskin wrote a poem titles On Skiddaw and Derwent Water, which was published in 1829 in the Spiritual Times. Wordsworth, Byron, and Scott, among other Romantic poets, captures his imagination. Teenage Ruskin was a sharp and eloquent speaker. When he was 15, he began compiling a mineral dictionary and submitted three papers on the subject to the Magazine of Natural History. His mother insisted on seeing him for tea every day while he was studying classics at Oxford University. He performed well in college, but an illness forces him to drop out in 1842, leaving him with just a double fourth degree in classics and mathematics (a grade lower than a third given by Oxford until 1971).

Mid Life

It’s easy to overlook the fact that Ruskin was an accomplished artist in his own right; he once compared the need to draw to the want to eat and drink. Since childhood, he kept sketchbooks packed with drawings of nature; blooms, flowers, mountains, stones, clouds, minerals, and birds. He created volumes of sketches and paintings of these subjects throughout his life. His watercolours imitated the expressive manner of J.M.W. Turner, and was most active between the years 1840 and 1870, when he created the majority of his work. The only thing that he didn’t professionally do was display his artwork; he otherwise utilised his studies to document what he observed and to help him with his writing. Despite the fact that many of his works were never shared, he did so however in his articles and books.

While still a young man, Ruskin published Modern Painters – Their superiority in Landscape Painting to all the Old Masters when he was 24 years old, a highly important book that began an attack on the artistic establishment. Artists like Claude Lorrain, Nicolas Poussin, and Salvator Rosa from the 17th century were attacked in the book. A different approach was pushed by Ruskin, who advocated for the faithful recording of nature and in particular supported the work of controversial artist J.M.W. Turner. The reasons and regulations set by Sir Joshua Reynolds at the Royal Academy were questioned by Modernist Painters. Ruskin’s words outraged many but his enthusiasm for subject matter gained him admirers, and Brotherhood, William Wordsworth, George Elliot, and Charlotte Bronte were all fans of his work at the time, as was the general public. There were a total of five volumes published by Ruskin, the latest of which came out in 1860. Artists in the United States were liberated by Modern Painters, which gained an enthusiastic audience there as well. John A. Parks, an artist, put it this way: “Since European painting has lost its hegemony, art may now be both an aesthetic and religious pursuit. This was Ruskin’s potent concoction, and American painters were enamoured with it”.

For Ruskin, the architecture of Venice was especially beautiful, therefore he was against restoration to the point of scaling a scaffolding to dispute with stonemasons. A three-volume treatise on Venetian art and architecture, The Stones of Venice, immortalised his convictions, in which he expanded on ideas he had developed in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), an extended essay in which he claimed that the most important principals of architecture were sacrifice, truth, power, and beauty. Chapter On The Nature of Gothic, which Ruskin wrote for The Stones of Venice, argued that architecture reveals the spiritual and moral condition of society in which it was created. He loved mediaeval Christian civilisation for its flaws, which reflected the individuality and skill of the individual skill artisan, but also for the fact that it was collective art, motivated by a devotion to God. He admired it. He saw it as a counterpoint to the classical style’s regularity and geometric forms, which signified coldness, an attempt to maintain control, and a “haughty aristocratic style” to him. Classical architecture, in Ruskin’s view, signified a decline from a civilised state.

Despite moving away from art criticism, many people regarded this as Ruskin’s finest work. Unto This Last tackled the complex subject of capitalism and the resulting dehumanisation as part of an indictment. He made a personal appeal to his readers to help create a better society in this passionately written book, and it was met with astonishment. He decried industrialism’s ugliness and the harm it was doing to the environment. His criticisms of child labour included a plea to business leaders to inquire if their children would be asked for such employment.

Friends and colleagues alike were enraged at the conclusion of the book. Some thought his ideas were dated, while others saw him as a self-righteous jerk. Reading the book was like being “preached to death by a mad governess” by an insane governess, according to one review, while “if we do not crush Ruskin, his wild works will touch the springs of action in some hearts and before we are aware, a moral floodgate may fly open and drown us all.” according to a second. However, the work’s importance cannot be overstated, since many of the British Labour Party’s founders, including, including economist John A. Hobson, were inspired by it. Mahatma Gandi was motivated t become an activist after reading Unto This Last, which he then translated into Gujarati for the benefit of India’s working class. ‘I think that some of my innermost beliefs have been mirrored in this wonderful work of Ruskin and that is why it is grabbed me and made my life change,’ Gandhi said.

A family friend 10 years his age, Ruskin married the lovely Euphemia Gray (better known as Effie) in 1848. Unfortunately, Ruskin failed miserably, unable to meet the young woman’s needs or resist the overwhelming influence of her mother. The fact that the union was never completed is a well-known fact regarding the couple’s union. Anecdotally, it is said that Ruskin had to cancel his wedding night performance because his young bride had pubic hair, unlike ladies in his paintings, he had grown up adoring and had influenced him. Effie stated that her husband “had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his wife was because he was discussed with my person the first evening” which is most likely fictitious. Ruskin shared this view when he said that “Some may find it odd that I would refuse to date someone who was so visually appealing. However, despite her attractive appearance. her character was not built to arouse desire. Contrary to popular belief, some aspects of her life acted as a full check on it” a good place to start. The companion of John Ruskin, Clive Wilmer, said this John Ruskin: “A terrible marriage is the fault of both parties, and the unfortunate guy was no exception. He has flows, which one should not pretend did not exist – he was dogmatic… he could be very pompous – but he was incredibly well-versed in his field.”

John Ruskin painted Effie in The Order of Release, which he painted in 1852 after meeting John Everett Millais. After that, Millais followed the couple to Scotland, where he painted John Ruskin. Effie and he had a romantic relationship at this time period. Effie sought for divorce from Ruskin after returning to London. Despite the fact that the marriage caused a huge public scandal, it was declared null and void in 1854 due to “incurable impotency” Following this, Effie married Millais with whom she would have been additional eight children. Effie Gray, a 2014 film starring Emma Thompson, was based on the true story of the incident.

A young student named Rose La Touche was Ruskin’s love interest around the time of his 1865 book Sesame and Lillies. He proposed to her about that time as well. After exchanging letters with Effie, her parent refused to give their consent. The next year when Rose became 18 and could make her own decisions (he was 47 at the time), Ruskin offered to marry her again. This time, Rose said no. Ruskin was devastated when Rose dies in 1875 at the age of 27, allegedly from anorexia. Rose’s death tormented him, and he turned to spiritualism to make touch with her in the hereafter. As time passed, he began to exhibit symptoms of the severe mental illness that would follow him throughout his time.

Late Life

At Oxford’s Slade School of Fine Art, John Ruskin was named Slade Professor of Art in 1869. Although it was his first time as a teacher, Ruskin had been engaged in education since the 1850s, when he became a well-known speaker. In 1871 John Ruskin founded his own art school, The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. In addition, he extolled the values of volunteerism and hard work. Ruskin donated £5000 of his own money to the school. As early as 1879, Ruskin withdrew from Oxford, but returned in 1883, only to leave again the following year due to a disagreement with university official over the expansion of the Drawing School, and his worsening health. During this time, he continued to put his political ideas into practice by publishing the “workmen and labourers” magazine Fors Claviger and founding the Guild of St George, a utopian society that promoted traditional crafts and amassed a substantial collection of art, books, and historical object. The Bible of Amiens and Mornings in Florence are among the travel books he penned.

In 1871, he purchased Brantwood, a Lake District mansion that is now a museum dedicated to the work of John Ruskin. he spent the remainder of his life there, where he revelled in the simple pleasures of home décor, gardening, and baking.” It’s possible that his periods of severe despair and crisis, which began in the late 1870s, were symptoms of bipolar illness. Joan Severn, his second cousin and executor of his will, took care of him till his death. As a result, in 1878, he became persuaded that his beloved Rose had returned from the grave, screaming out in insanity for “Rosie-Posie” and yelling “Everything white! Everything black!” After his death in 1900 at the age of 80 from influenza, he had little money left over to his family. Despite the fact that he had received at least £120,000 from his father, he had donated the vast majority of it to charity.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts Movement owe a lot to Ruskin’s literature, which played a key role in it. It was a revolutionary approach to art criticism, and it had a profound impact on succeeding generations. Michael Bracewell, a writer, writes: “Ruskin’s fervent support for specific artists opened the way for reviewers like David Sylvester and Robert Hughes in the following decades. Contemporary art criticism is severely lacking in rigour and knowledge of this kind.” Famous authors like Marcel Proust and Charlotte Bronte admired Ruskin. Leo Tolstoy said when Ruskin died: “John Ruskin was one of the most remarkable men not only of England and our time, but all countries and all time.”

But it wasn’t only his writing or creative ability that changed the world; it was his radical viewpoints as well. Ruskin’s social conscience, as described by William Morris as “He seemed to point out a new road on which others should travel” played an important role in improving society both in Britain and abroad. He advocated for the education of women and delivered lectures to the working class that helped to better their lot in life. With his own money, he built a land trust called the Guild of St. George, where individuals could come together and cooperate on projects. The guild is currently a non-profit organisation dedicated to promoting the rural economy via arts, crafts, and other creative endeavours. As a result of Ruskin’s passion for the Lake District, a movement to preserve and maintain the landscape was born, and the National Trust was founded as a result of that movement. Additionally, his ideas contributed to the establishment of the British “Wealth State,” which included universal health care, a minimum wage, and benefits for the poor and needy.

Even 200 years after his death, Ruskin still has a fascination for many people. Daisy Dunn, an art historian, points out the following: “It’s safe to say that Ruskin was a man of many contrasting opinions. He compared swimming against the current to that of a fish. Even though he identified as a conservative, he had a socialist bent on many of his views. He was a firm believer in the hierarchy, but he also thought that the wealthy had a duty to look out for the less fortunate.” He’s even credited for predicting climate change’s calamities. On the Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century he prophesied that “a period which will assuredly be recognised in future meteorological history as one of the phenomena hitherto unrecorded in the courses of nature.” Scholar of literature Marcus Waithe once stated: “There has been a lot of evidence to support Ruskin’s dire predictions about air pollution. In the same way that he was concerned about river and spring cleanliness, people are now concerned about plastic contamination in our seas.”

Famous Art by John Ruskin

Loggia of the Ducal Palace, Venice (1849-50)

1849-1850

In spite of the fact that Ruskin never referred to himself as an artist, a study of his drawings and paintings of Venice provides a clear grasp of his views. Watercolour depicts Venice’s most renowned Gothic loggia (covered outside the gallery), with Saint Mark’s Basilica in the background, meticulously researched by the artist. Drawing and composition skills are on full display in this watercolour, which shows his mastery of both. Elements of Drawing, published in 1857, was Ruskin’s first major book in which he outlined his style and painting methods. When it came to the philosophy behind Impressionist painting, Claude Monet stated in 1900 that “ninety per cent of the theory of Impressionist painting is in… Elements of Drawing.”

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- Ruskin was a complicated, passionate, and highly eloquent guy who influenced individuals like Mahatma Ghandi, Leo Tolstoy, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

- As an art critic and patron, he was also a brilliant watercolourist, a dynamic teacher, a well-respected geologist, and a passionate advocate for social and political reform.

- He was a real polymath.

- These driving forces – nature, God, and society – appear often in his writings, and they shaped his forward-looking views.

- He fought for new painting techniques, historic building preservation, natural landscape conservation, women’s education, and better working conditions for the poor.

- He also foresaw dangers connected with the Industrial Revolution, such as pollution, decades before the general public did.

- His thoughts and writing helped young artists gain recognition, aided in the creation of the National Trust, and safeguarded Venice’s historic architecture.

- His ideas influenced welfare changes in the United Kingdom, such as the minimum wage, free school lunches, and universal health care.

- among others.

- More than 50 volumes, covering everything from art criticism to fiction, political treaties, to travel guides, were published by Ruskin, who was a prolific writer.

- In these works (which included lecture notes and letters as well as more traditional essays), he shared his revolutionary ideas, and over the course of his career, he streamlines his writing style to make it as accessible as possible to the widest possible range of readers.

- He was a staunch supporter of “truth to nature” as an aesthetic principle encouraging artists to pay careful attention to the landscape and, as a result, to accurately depict nature without romanticising what they observed.

- The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of youthful painters who rejected current ideas of aesthetic beauty in favour of a pre-Renaissance style of painting, benefited greatly from this concept.

- Due to his focus on nature (as well as his distaste for mass manufacturing), John Ruskin had a significant influence on the growth of the Crafts, Movement.

- To many, Ruskin’s work on Neoclassicm encouraged the restoration of the older Gothic style, which he championed with fervour.

- As a result of his influence on many other architects such as Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright as well as Walter Gropius, it’s said that he helped to launch the Garden City Movement.

- In Ruskin’s min, nature and beauty were intimately linked to notions of the divine, because of his upbringing as a Christian, His conclusion was that portraying religion was best done via realistic depictions of nature and the human body, rather than grandiose religious events.

- The Pre-Raphaelites took this to heart, and their art sought to harmoniously integrate religious devotion.

- Instead of idealising religious figures, they portrayed them as members of the working class with filthy clothing and fingernails, which earned them scorn.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses