(Skip to bullet points (best for students))

Born: 1834

Died: 1903

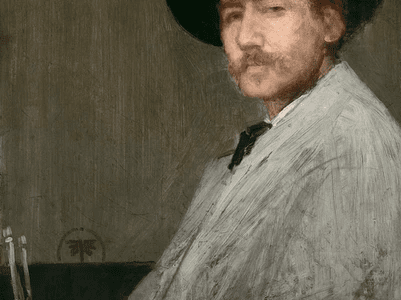

Summary of James Abbott McNeill Whistler

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, one of the most important pioneers in contemporary art and a predecessor of the Post-Impressionist movement, is known for his unique painting technique and quirky personality. He was brash and confident, and he rapidly earned a reputation for retaliating verbally and legally against art reviewers, dealers, and artists who disparaged his work. His paintings, etchings, and pastels exemplify the contemporary desire to create “art for art’s sake,” an ethos championed by Whistler and other Aesthetic movement figures. They also reflect one of the early transitions from conventional representational painting to abstraction, which is central to much modern art.

Whistler abandoned Gustave Courbet’s Realism in favour of his own trademark style, in which he began to explore the possibilities and limitations of paint, much like Édouard Manet at the period. Whistler demonstrated a new compositional technique by restricting his colour pallet and tonal contrast while skewing perspective, emphasising the painting’s flat, abstract character.

Whistler used words like “symphony,” “arrangement,” and “nocturne” in his titles (or re-titles) to indicate a link between musical notes and colour tone changes. These more abstract titles drew the viewer’s attention away from the real subject matter represented and onto the artist’s use of paint.

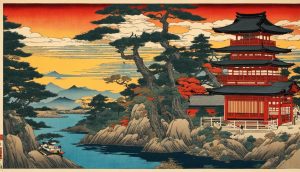

Whistler was a staunch supporter of the Aesthetic movement, promoting “art for art’s sake” in writings like The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1892), and he also contributed to the development of new ideas about beauty by employing unconventional models reminiscent of Pre-Raphaelite figures and, most notably, by incorporating the Japanese aesthetic into his imaginative compositions.

Many early modern painters in Paris were enthralled by Japanese art. Whistler is recognised with pioneering the Anglo-Japanese style in fine art since he was one of the first American artists working in England to include delicate oriental fabric designs and props into his work. The Peacock Room, for example, was crucial in spreading the Japanese aesthetic to England and America.

Whistler’s libel suit against John Ruskin, as well as other defensive measures against art critics who did not share his vision, inspired modern artists, such as the Impressionists, to look beyond traditional art institutions when seeking exhibition space or support for their work, just as Courbet’s Pavilion of Realism questioned the authority of the French Salon.

Childhood

McNeill, James Abbott Engineer George Washington Whistler and his devoutly Episcopalian second wife Anna McNeill had a son named Whistler. Whistler had a turbulent childhood and was prone to mood swings. His parents immediately saw that sketching calmed him down, so they encouraged him to pursue his creative interests. When Whistler’s father was hired by Tsar Nicholas I to build a railroad in 1842, he went to St. Petersburg with his father, mother, and younger brother William (later a Confederate army surgeon). Sir William Allan, a Scottish painter commissioned by the Tsar to make a picture of Peter the Great, demanded on seeing the precocious youth’s sketches.

Allan pushed Whistler to develop his abilities, and he joined at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in 1845, when he was 11 years old. When Whistler’s father died of cholera four years later, the family moved to the United States, settling in Pomfret, Connecticut. Despite their poor financial circumstances, Whistler’s mother worked hard to keep her children ethically grounded and to provide them with every chance. In the hopes that he might pursue a profession as a preacher, she sent James to Christ Church Hall School and read Bible Scriptures to him every morning.

Her son, on the other hand, was undeterred in his pursuit of art. Whistler enrolled in the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1852, where he studied drawing under Robert W. Weir, but was expelled soon after due to his dislike to authority and poor academic performance. Whistler’s ability to make maps, which he learned at West Point, helped him land his first job as a topographical draughtsman with the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey when he graduated. The artist learnt the etching method during his two-month stay, a talent he would subsequently utilise to make 490 etchings, drypoints, and mezzotints. Whistler departed for Europe in 1855, determined to make a living as an artist.

Early Life

In more ways than one, Whistler had a thorough education in Paris, where he temporarily studied at the Ecole Imperiale before enrolling in the workshop of Swiss painter Charles Gabriel Gleyre, who subsequently taught Impressionists Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. The 21-year-old rapidly adopted the style of a bohemian artist after being separated from his mother’s religious influence. He assumed the laid-back demeanour of a well-dressed flâneur, wandering aimlessly around Parisian boulevards and soaking in every aspect of his surroundings. Friends called him “Jimmy,” and he spent his money on clothing, cigarettes, food, alcohol, and art materials.

He was frequently forced to pawn his belongings or rely on the kindness of others to pay off his increasing debt. Whistler, a fan of 17th-century Dutch and Spanish painters, reproduced their works in the Louvre and sold them to aid with his financial difficulties. Whistler’s true artistic development began in 1858, when he met French painter Henri Fantin-Latour and met Realist painters Gustave Courbet, Alphonse Legros, and Édouard Manet through him, as well as poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, who is credited with coining the term “modernity” to describe the fleetingness of the urban experience.

At the Piano, Whistler’s painting technique was heavily affected by Courbet’s realism at this early stage, as evidenced by the earthy hues and highly textured surfaces (1859). At the Piano, painted the same year the artist moved to London, portrays a mother and kid, the artist’s half-sister and niece, in their London home’s music room. When it was presented at the Royal Academy in 1860, the picture was highly appreciated. Whistler, however, abandoned this Realist perspective within a few years in favour of a whimsical style that was more closely linked with Aestheticism in terms of decorative quality. His use of oriental props and commitment to Japanese aesthetic ideals distinguished him even more from the Realists, propelling him to new heights within the Aesthetic movement.

Mid Life

Whistler moved to London permanently in 1859, although he regularly travelled to and exhibited his work in continental Europe, notably France, but not always with the success he desired. The Royal Academy in London and the French Salon, for example, both rejected his portrait of his mistress Joanna Hiffernan, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (1862). In 1863, the rejected picture was shown in the Salon des Refusés with work by other avant-garde painters, including Édouard Manet, under the title The White Girl.

The White Girl, like Manet’s Le dejeuner sur l’herbe (1863), was ridiculed by more conservative audiences at the time but is today regarded as an important early example of contemporary art. It is the first of several paintings by Whistler that used colour to investigate spatial and formal relationships in a visually exciting way, in keeping with the Aesthetic belief in “art for art’s sake.”

The painter was as daring with a brush as he was with his travels. Whistler unexpectedly sailed to Valparaiso, Chile, in 1866. Some academics believe he was sympathetic to the Chilean army at the time, which was at war with Spain, and that he travelled there to aid the Chilean war effort. Whistler produced three seascapes that represented a departure in his creative repertory, regardless of why he travelled there. These nighttime harbour vistas, first named “moonlights” but subsequently modified to “nocturnes” inspired Impressionist views of the Thames River and Cremorne Gardens when the artist returned to London.

Impressionism was introduced to Whistler by fellow artists Claude Monet and Camille Pissaro, who had briefly fled to London in 1870 to avoid the Franco-Prussian War. Whistler produced his “nocturnes” at this time by painting thin layers of paint with brilliant colour flecks to resemble faraway lights or ships. For English Aesthetic painters unfamiliar with Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints and Asian porcelain gathered by Whistler and his French counterparts, Japanese aesthetic concepts like as reduced shapes and expressive lines, visible in these works, were a novelty.

Whistler’s “nocturnes” illustrate his modernist obsession with producing an overall effect at the expense of individual details and exact depiction, similar to his portraits and aligned with French Impressionist ideas. In reality, in 1874, Whistler was asked to attend the Impressionists’ first group show, but he rejected.

Whistler continued to create portraits for the following ten years, despite painting marine “nocturnes” Arrangement in Gray and Black or Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, his best-known piece, was made at this time (1871). The painting was a huge success for him, but the arrival of his mother in London in 1864 put a serious dent in his carefree lifestyle. When the twenty-nine-year-old Whistler discovered of her intentions to stay with him, he was obliged to clean out his life, which included transferring his then-mistress Joanna Hiffernan out of his house and into an apartment.

Whistler’s reputation as a smart, outspoken guy blossomed alongside his fame as an artist. At a party, he once defeated Oscar Wilde by pointing out the author’s propensity of plagiarising brilliant words (including some of Whistler’s own). However, the artist suffered from erratic mood swings and a short fuse, both of which he had struggled with since infancy. Whistler’s relationship with his mistress Joanna Hiffernan fell up as a result of his wrath and jealously when she posed naked for his friend Gustave Courbet.

Whistler’s dominating personality harmed his career as an artist at times. Whistler’s Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room (1876-77) caused considerable friction between the artist and his patron Frederick Leyland, and is now regarded as the best example of Anglo-Japanese aesthetic fusion and the most significant contribution to Aesthetic interior design. Whistler was a huge fan of Japanese prints and ceramics. So when Leyland requested him to make a few small alterations to his dining room in order to display his own porcelain collection, Whistler gladly agreed. However, the artist’s changes were more comprehensive than planned, resulting in a payment dispute.

Whistler also had disagreements with critics. He created his own theory of art to explain his approach to painting, which he defined in 1873 as “the science of colour and ‘picture pattern’.” Whistler sued John Ruskin for libel after what he saw as an assault on Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1874) in the guise of a bad review. Despite the fact that the artist won, the judge’s award of a single farthing, the equivalent of cents, sent a powerful message about the court’s view of the case. Whistler’s inability to pay his high legal expenses nearly bankrupted him.

Late Life

Whistler was evicted from his London house in 1879 because he was insolvent. He came to Venice with his new mistress, Maud Franklin, to complete a contract from the Fine Art Society to make a series of etchings. Whistler also made several pastel and watercolour paintings, as well as more than fifty etchings of Venice settings, during his fourteen-month stay. When his etchings of the Italian city were shown in London in 1880 and 1883, they were highly received, and demand for his pastels grew.

He continued to paint portraits in his latter years, experimented with colour photography and lithographs, and released two books: Ten O’clock Lecture (1885) and The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890). Whistler was very aware of his public character and worked hard to maintain his reputation as a successful artist. Friends ascribed his “wickedness.” to his wearing a monocle and strolling with a bamboo walking staff, with a single white forelock in his otherwise dark hair. He was notorious for advising ladies on what to wear to his exhibitions so that their clothing would not clash with the colours in his works, since he was always aiming for control.

By the 1890s, Whistler had also developed his own distinctive signature: a butterfly with a stinger for a tail, possibly a reference to his delicate touch and sharp tongue. Whistler married Beatrix Godwin, a former pupil and friend, in 1888. Her contacts helped him obtain additional commissions for employment because she was a respectable woman. The pair finally relocated to Paris, where Whistler built a studio and had a period of tremendous production before his wife died of cancer in 1896. Whistler later established an art school, but his declining health rendered the endeavour unworkable. Whistler died in 1903, barely two years after the school closed in 1901.

Whistler, like Courbet, established an artistic identity and zealously defended his work, inspiring future generations of painters to take on art authorities. Despite the fact that his painting technique was too radical for many Victorians, the artist was recognised with introducing contemporary French painting to England by the time he died, as stated in London’s Daily Chronicle: “The classic case of ‘Whistler against Ruskin’ was tried twenty-five years ago. It may take two hundred years in the history of art for the critics’ and public’s perspectives to shift, and for the dazzling brilliance of the man Ruskin referred to as a “coxcomb” to be justified.”

Famous Art by James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Symphony in White, No.1: The White Girl

1862

This picture, originally named The White Girl, portrays Whistler’s mistress and model Joanna Hiffernan, a young woman with long, flowing red hair and a plain white cambric outfit. She stands on a bearskin rug with a similar colour scheme and a white flower at her side, her faraway look giving her a doll-like appearance. Indeed, Whistler uses her as a toy or pawn in that he is more interested with utilising the canvas as a way of exploring tonal variations than with the authenticity of portraiture. This goal is further clarified by Whistler’s later renaming the painting Symphony in White, No.1: The White Girl, which draws attention to the work’s various white tones and suggests a connection between them and music notes.

The artwork holds the distinction of being the artist’s first piece to acquire true renown. The painting was rejected by the Royal Academy of London and the Salon of the French Academy for its inappropriate subject matter, which seemed to suggest the loss of innocence, but it was accepted into the Salon des Refusés in 1863, where it was admired by Édouard Manet, Gustave Courbet, and Charles Baudelaire, among others.

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket

1875

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875), the last of Whistler’s nocturnes and one of only six portraying London’s Cremorne Gardens, depicts an explosion of fireworks in the night sky. The artist depicts the impact of fireworks over the river rather than providing a precise depiction. He succeeds in capturing a sense of joy and celebration in this way. The painting exhibits the Aesthetic ideal “art for art’s sake” by portraying what Whistler characterised as a “dreamy, pensive mood,” rather than a distinct narrative, with sweeping brushstrokes of dark blues and greens punctuated by tiny bursts of bright colour.

Little Venice

1880

Little Venice (1880) is one of more than fifty etchings Whistler made during his fourteen-month sojourn in Italy in 1879, measuring less than a foot in height and breadth. When these etchings were shown in London, he had already established himself as a master painter. They were highly welcomed and displayed his ability to work in a variety of mediums. Whistler displays the natural elements of water and air dominating the urban area, which is quite small. The use of free, expressive lines to convey the ethereal splendour of the city, rather than a topographical rendering, reflects his modernist approach to painting.

BULLET POINTED (SUMMARISED)

Best for Students and a Huge Time Saver

- James Abbott McNeill Whistler, one of the most important pioneers in contemporary art and a predecessor of the Post-Impressionist movement, is known for his unique painting technique and quirky personality.

- He was brash and confident, and he rapidly earned a reputation for retaliating verbally and legally against art reviewers, dealers, and artists who disparaged his work.

- His paintings, etchings, and pastels exemplify the contemporary desire to create “art for art’s sake,” an ethos championed by Whistler and other Aesthetic movement figures.

- They also reflect one of the early transitions from conventional representational painting to abstraction, which is central to much modern art.

- Whistler abandoned Gustave Courbet’s Realism in favour of his own trademark style, in which he began to explore the possibilities and limitations of paint, much like Édouard Manet at the period.

- Whistler demonstrated a new compositional technique by restricting his colour pallet and tonal contrast while skewing perspective, emphasising the painting’s flat, abstract character.

- Whistler was a staunch supporter of the Aesthetic movement, promoting “art for art’s sake” in writings like The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1892), and he also contributed to the development of new ideas about beauty by employing unconventional models reminiscent of Pre-Raphaelite figures and, most notably, by incorporating the Japanese aesthetic into his imaginative compositions.

- Many early modern painters in Paris were enthralled by Japanese art.

- Whistler is recognised with pioneering the Anglo-Japanese style in fine art since he was one of the first American artists working in England to include delicate oriental fabric designs and props into his work.

- The Peacock Room, for example, was crucial in spreading the Japanese aesthetic to England and America.

Information Citations

En.wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Artists

Responses